REMNANTS OF A SEPARATION

INTRODUCTION

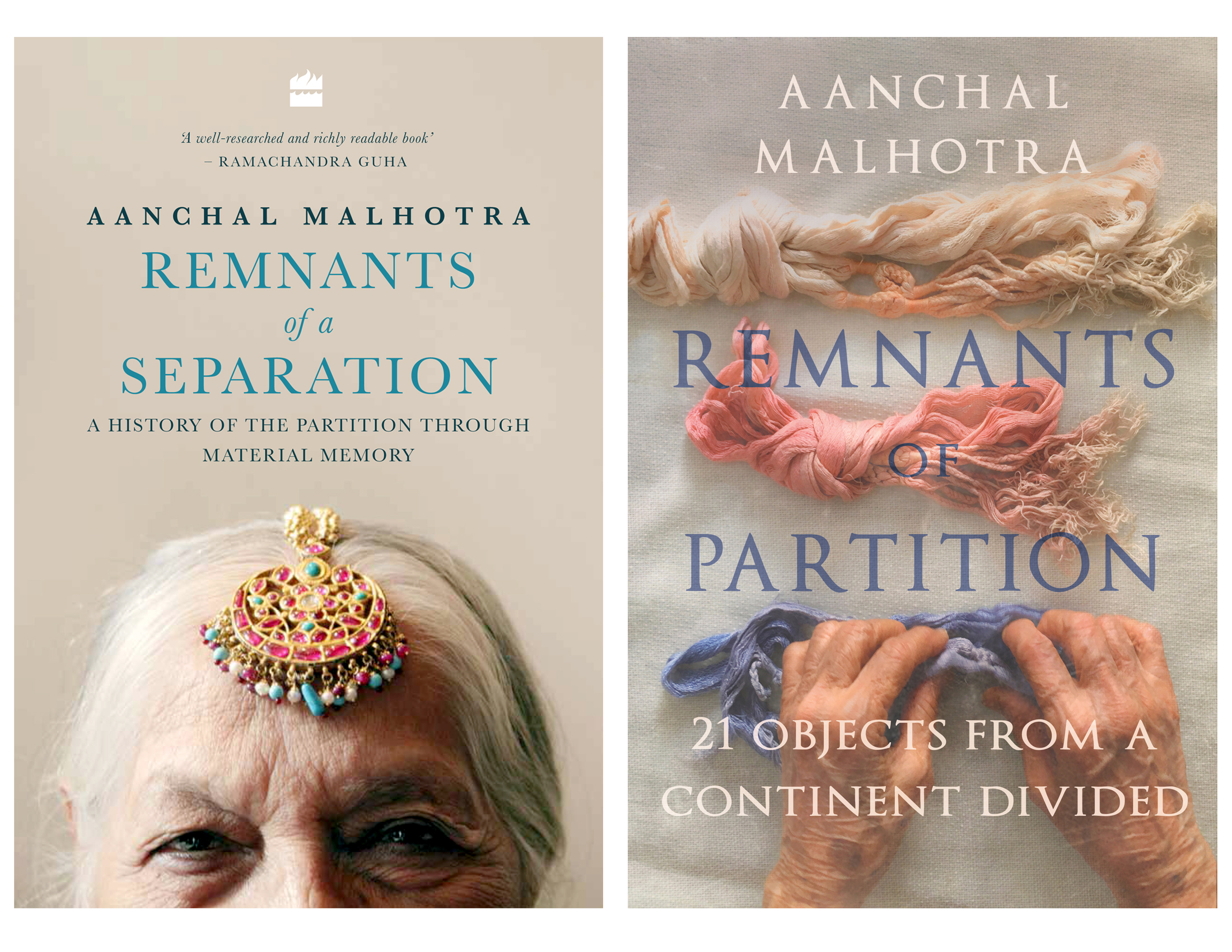

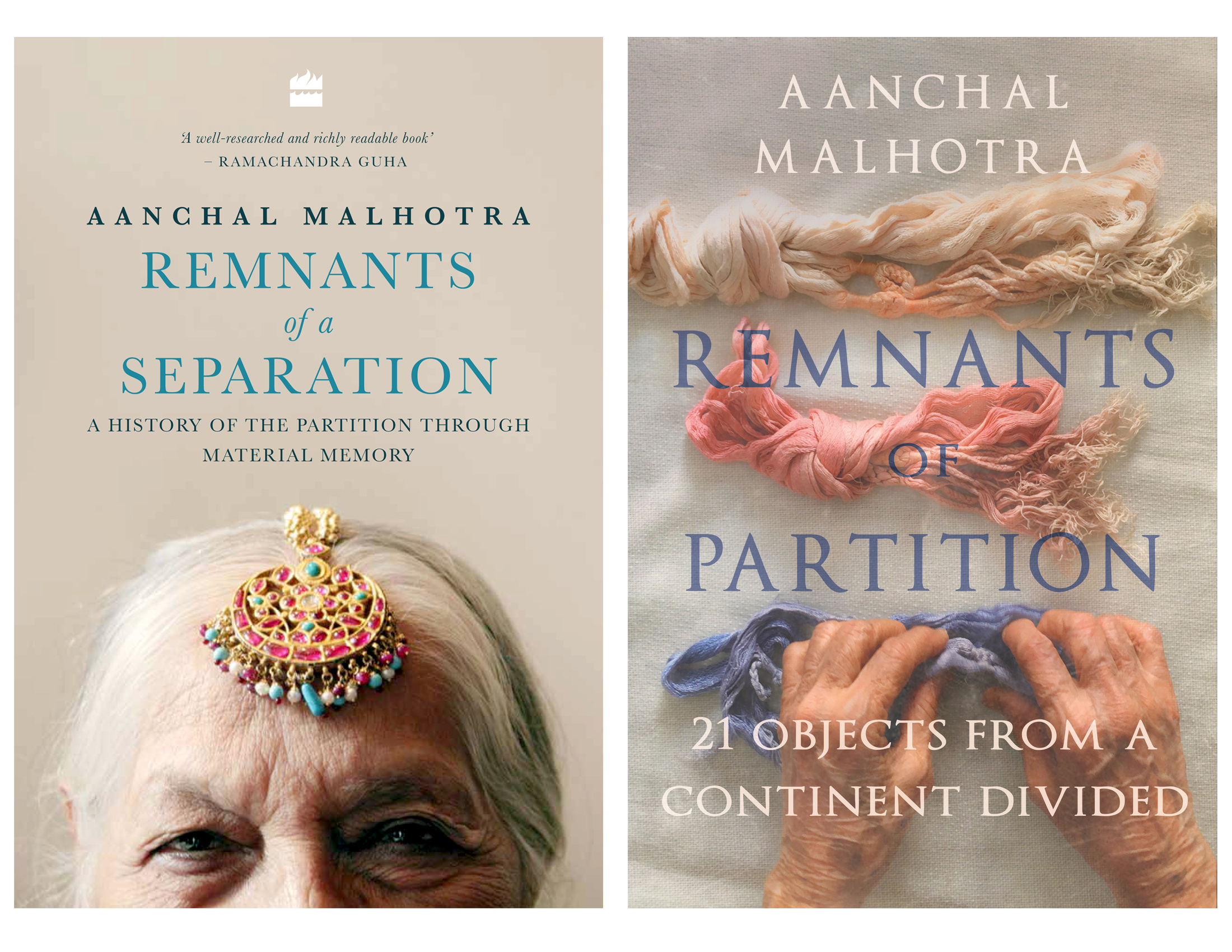

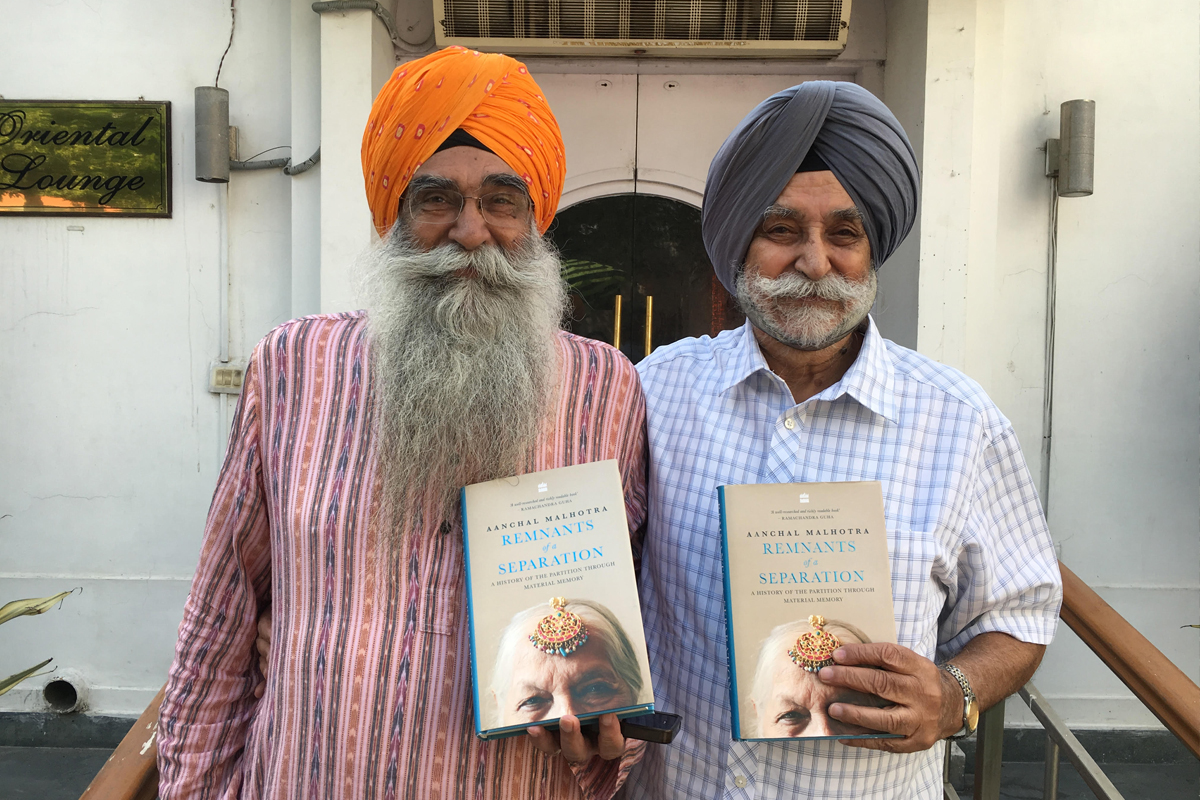

Remnants of a Separation began in 2013 as Aanchal Malhotra's MFA thesis project, whose research was conducted across India, Pakistan and the UK, with initial funding from the graduate program at Concordia University, Montréal, and in collaboration with The Citizens Archive of Pakistan (CAP). It is the first and only study of the belongings carried by refugees migrating across the border during the Partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947. These objects, both public and private in nature, tell stories of families, society, love, relationships, loss, displacement and yearning for a home that now exists on the other side of an unnatural divide. Remnants is a multidiscinplary project that includes text, photographs and audio recordings. It was first exhibited in its visual form at the Galerie FoFA, Montréal in 2015 and has travelled to various institutions and literary festivals since. It was published as a book of non-fiction titled Remnants of a Separation: A History of the Partition of India through Material Memory (HarperCollins, 2017) within the Indian subcontinent, and Remnants of Partition: 21 Objects from a Continent Divided (Hurst, 2019) in the rest of the world.

Since its initial publication, Remnants has been shortlisted for various awards - Shakti Bhatt First Book Award, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay NIF Book Prize, Hindu Lit for Life Non Fiction Prize, Tata Literature Live! First Book Award, Publishing Next Printed Book of the Year, and the Oxford Book Cover Prize. It was a Hindustan Times India @ 70 book, has been called one of the most intriguing alternative histories of the Partition, and is considered essential reading on the subject. In 2019, it was shortlisted for the British Academy’s Nayef Al-Rodhan Prize for Global Cultural Understanding. By situating the work within an international six-book shortlist of “non-fiction that illuminates the connections and divisions that shape cultural identity worldwide,” the prize asserted the 1947 Partition of India to be an event that continues to shape and inform the identity of South Asians even today.

The following collection of text and images can either be viewed independently or as a companion Reading Guide to any edition of Remnants. To buy the book, visit South Asia / UK / USA / Canada / Australia

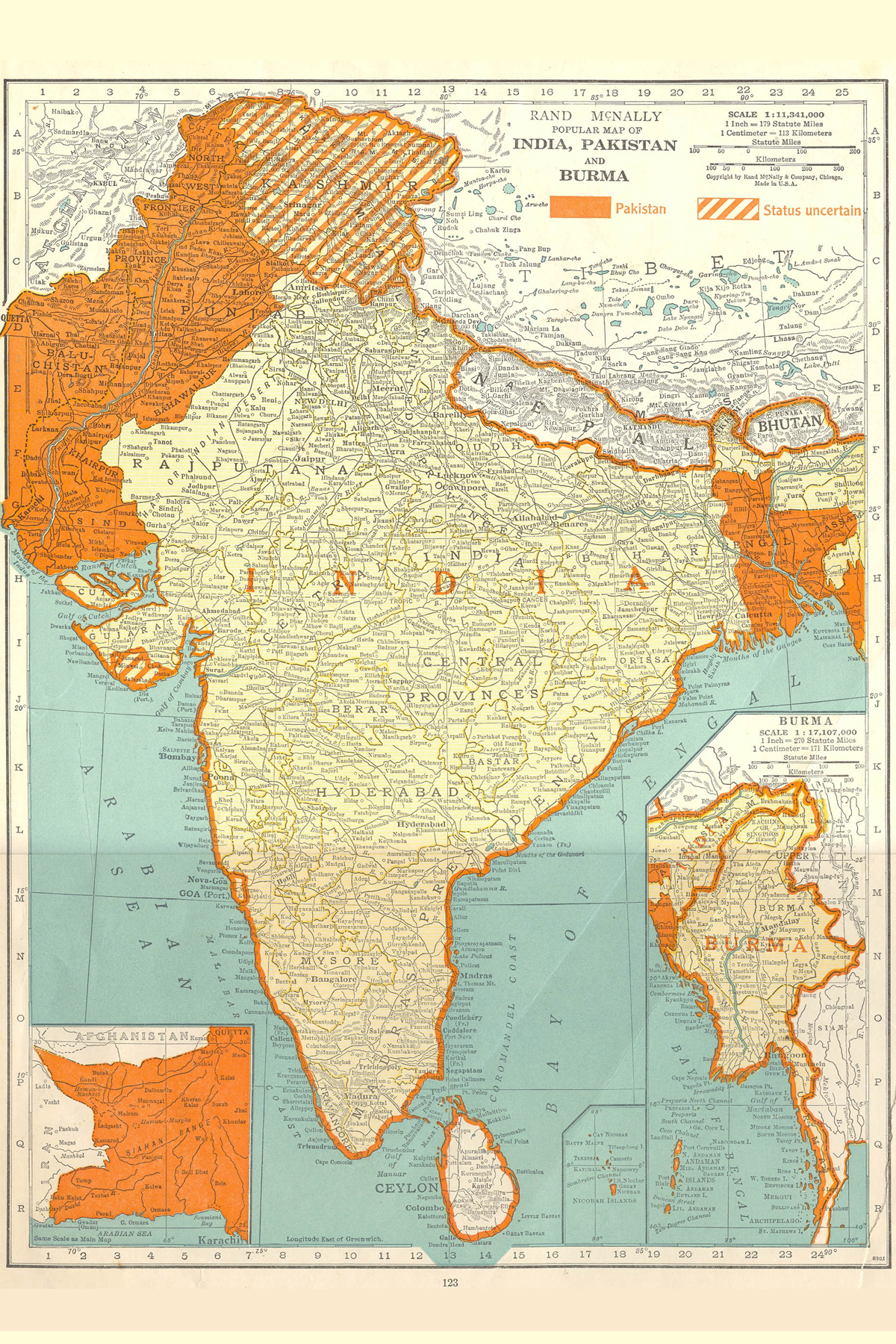

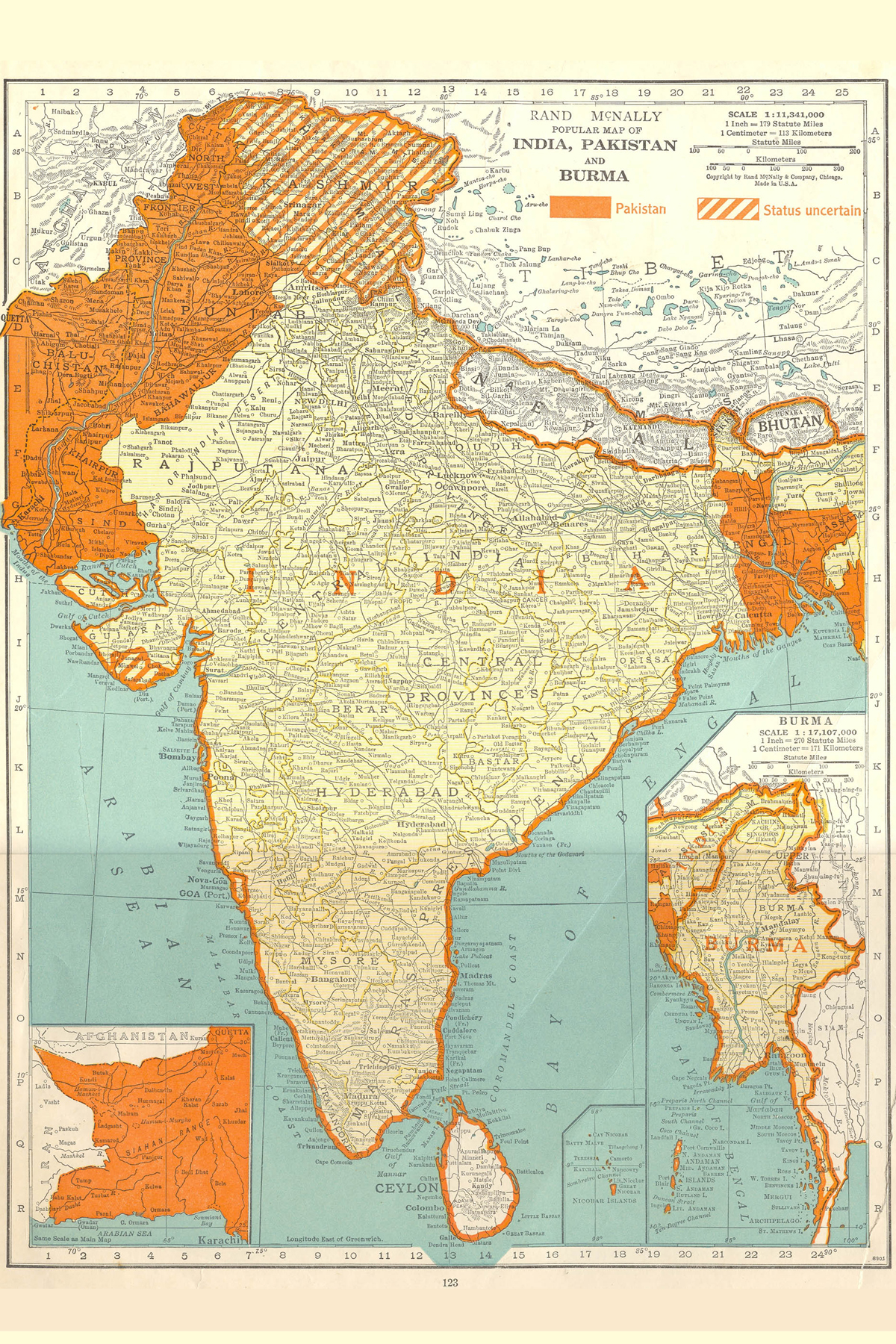

A SUB-CONTINENT DIVIDED

The withdrawal of the British Raj from Undivided India in August 1947 led to the drawing of the Radcliffe Line between the now independent nations of India and Pakistan, and forced Hindus and Sikhs to migrate eastward to India, and Muslims westward to Pakistan. The Partition is known to be the largest mass migration till date, displacing approximately 14 million people and killing another million. It is an event that quite literally shaped nations, and yet for the longest time its story was a story of silence. The fact that no official shared history of Partition exists across the countries involved – India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Britain – further fragments our understanding of the time. Over seven decades have passed, but Partition is not yet an event of the past.

And though it is often memorialized in terms of the vast numbers of casualties, it remains essential to recognize that behind each number is a story that deserves to be recorded and remembered for posterity. Stories of violence, displacement, homeland, loss, longing, belonging, identity, nationality, caste, family, friendship, reunion, and love. These first-hand testimonies are invaluable to the years that redefined the subcontinent. Yet, the vulnerabilities of the individual often find little space in our patriotic renditions of the past or nationalist climates of the present. In that sense, Remnants is an attempt to write a human history of the Partition.

A FAMILY HISTORY

The collection of one rupee coins belonging to Bhag Malhotra carried from D.I Khan, NWFP to Delhi in 1947. Read more

"My paternal grandfather, Balraj Bahri Malhotra, hailed from Malakwal, a small town in the Mandi Bahauddin district of Punjab, and grandmother, Bhag Gulyani, from Muryali, Dera Ismail Khan, in NWFP. The families of my maternal grandparents, Vishwanath Vij and Amrit Bery came from Choona Mandi and Shahalmi Darwaza, both in the Walled City of Lahore. All four families settled in the Capital city of Delhi in independent India, but the journeys of migration that they – along with many other families on both sides of the border – were forced to undertake enveloped their existence in a shroud of silence that only magnified as the years went by."

THE PARTITION LINE

The Indian Independence Act declared that India would be free from British rule on 15 August 1947. The Act also outlined a partition into the dominions of India, which was to be a secular nation despite its Hindu majority, and Pakistan, intended to be a homeland for Muslims. But were people expected to move across this border, or would they be allowed to remain where they were, despite their religious beliefs? The dangers of being stranded on the "wrong side" of a border - something no one could envision that early on - led many families to prematurely migrate by the end of 1946 or the beginning of 1947. Consequently, the belief that Partition would be merely temporary led many families to remain in their hometowns for months after the divide. Eventually, British barrister Sir Cyril Radcliffe was chosen as the architect of the new border, and given five weeks to Partition Undivided India. The border between India and Pakistan, the Radcliffe Line, bears his name.

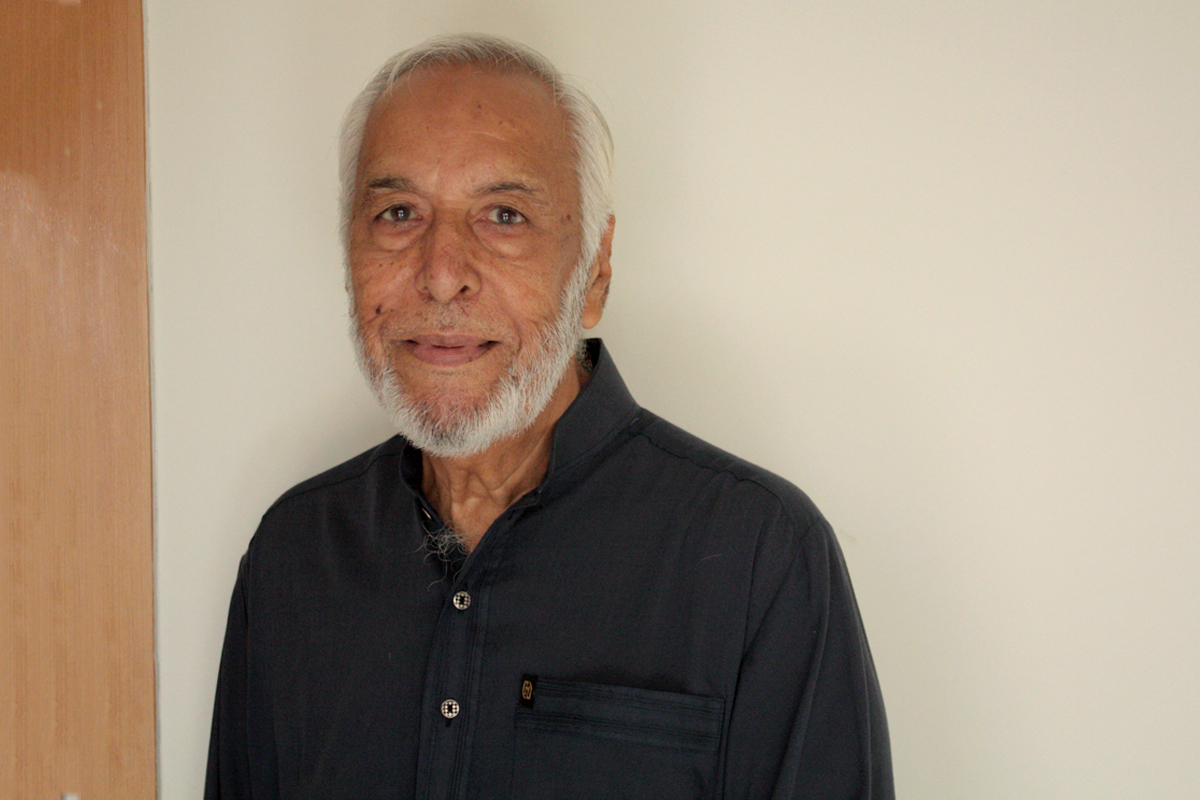

Amir Ahmed, born in 1936, in Nawabganj, Delhi, was eleven years old at the time of Partition and his family had decided not to migrate to Pakistan. ‘Partition showed us what the word insanity meant,' he lamented. Read more

Savitri Mirchandani, born in 1922 in Sindh, belonged to a family for whom the concept of Hindu or Muslim was secondary to their Sindhi identity. They remained in Karachi until late 1947, before taking a ship to Bombay.

Swarna Kapur, born in 1928 in dist Gujrat, traveled with her husband from Jhelum to Delhi in September 1947. On the platform she heard cries of “Hindu paani," and “Muslim paani.” Now even the water had been divided.’ Read more

Naeem Tahir, born in 1937 recalls the Sikh population of Bhoptiyan village, dist. Lahore converting to Islam after Partition, to be able to continue to live on land that was as much as theirs as their Muslims brothers.

Pran Nevile, born in 1922 in Lahore stressed on the amity and brotherhood he had witnessed between the people of various communities in his Walled City. 'The shared culture of Punjab had little to do with religion.'

Bhag Malhotra, born in 1932, recalls walking to school in Dera Ismail Khan, NWFP, in the early months of 1947 and being called a kafir (a disbeliever) all along the way despite having lived there her whole life. Read more

Prof. D.P Sengupta, born in 1936 in Barisal migrated to Calcutta in the summer of 1947. As the train pulled in to the station, he recalls seeing crowds of displaced people living in large cement pipes. Read more

ORAL HISTORY AND THE LIVED ARCHIVE

Through interviews, the collection of data and oral accounts, we study the ways in which individuals witnessed certain events in history. Oral History, thus, is not reportage or journalism, but rather, the very penetration of human memory. Memory, which becomes unreliable and malleable as time passes, ironically remains the sole informant in recreating personal history – an accumulation of which, in the case of the Partition of India, can help formulate collective history. The point in this collection of vast memory is to find new ways to understand the existing past. In countries like those of the subcontinent, where a rich tradition of oral culture exists and outweighs official archive, Oral History becomes one of the most authentic sources to recreate and understand a certain time.

MATERIAL MEMORY

Sometimes, memory can settle into objects in such a way that they become the only physical evidences of belonging to a certain place at a certain time. In the case of the Partition, Material Memory remains an incredibly important way of understanding personal and collective histories. The notion that where one is from can be understood using what remains of that place, opens up a highly sensitive and rich terrain that can help unpack belonging, especially if that place has now been rendered inaccessible by national borders. The stories in Remnants strive to appreciate the object in its totality, not as something that blends into the landscape of the past but as a primary character around which the entire landscape is arranged.

A peacock bracelet belonging to Rajni Malhotra, bought by Narain Das Bery in Lahore in 1930, and carried to Delhi

A fern-shaped brooch, belonging to Jiwan Vohra, bought by Narain Das Bery in Lahore in 1930, carried to Toronto

Singer Sewing machine belonging to Bhag Gulyani, bought in 1948 while living at Kingsway Refugee Camp, Delhi

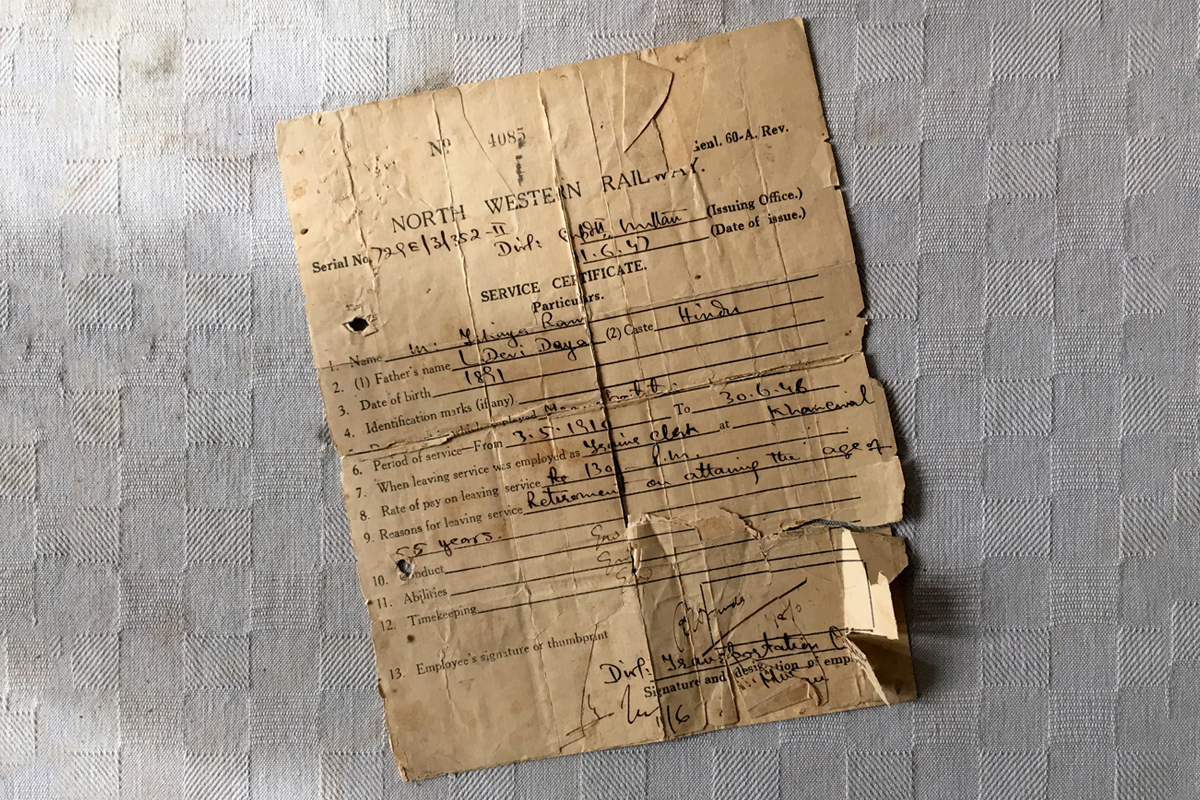

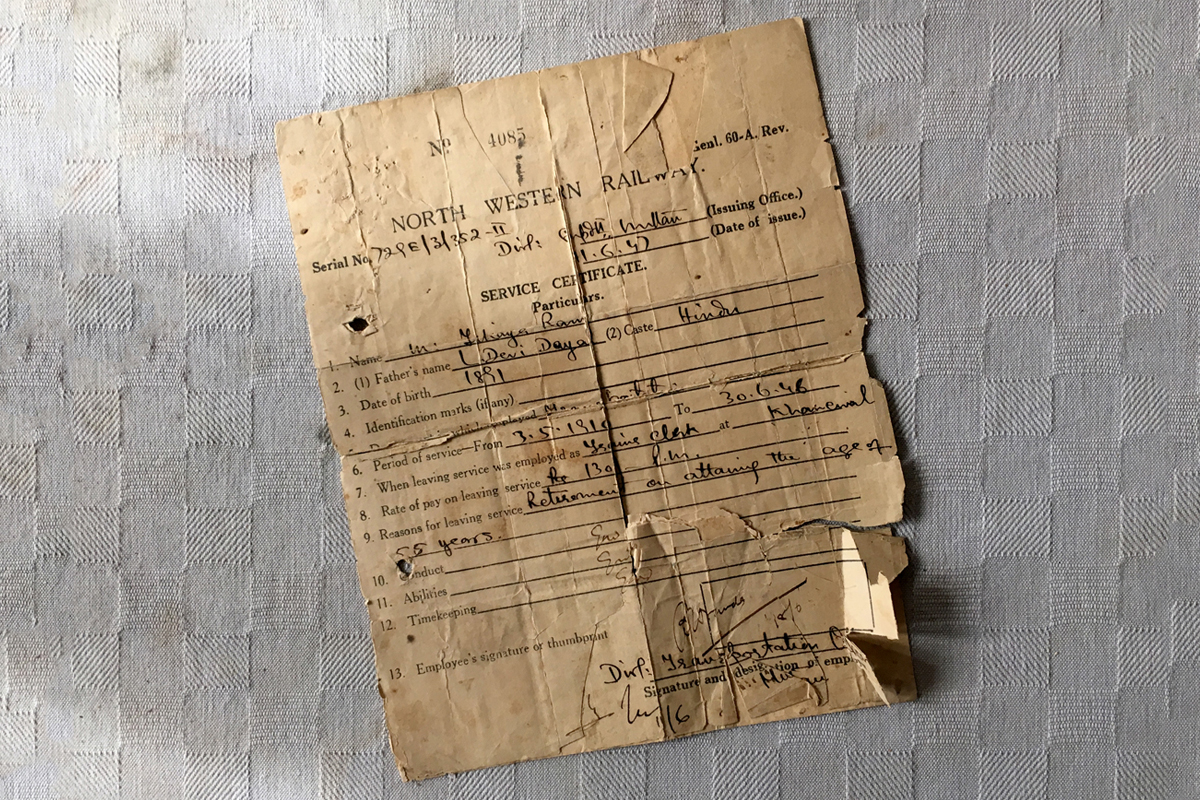

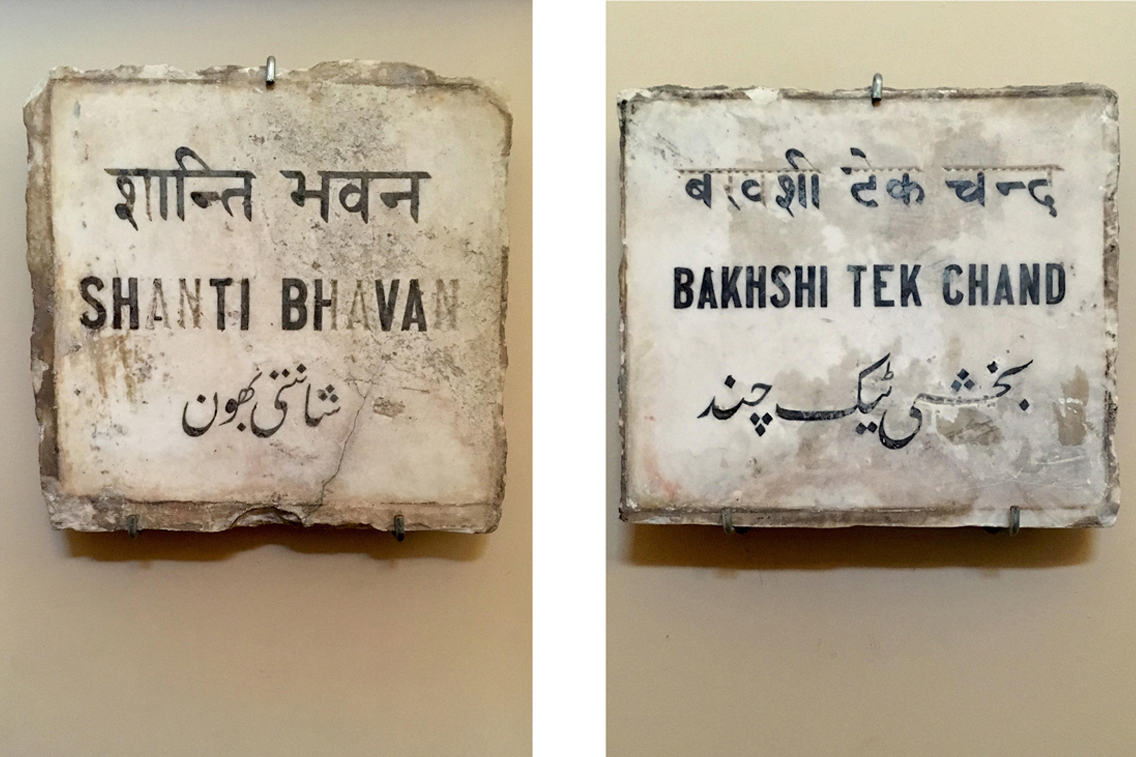

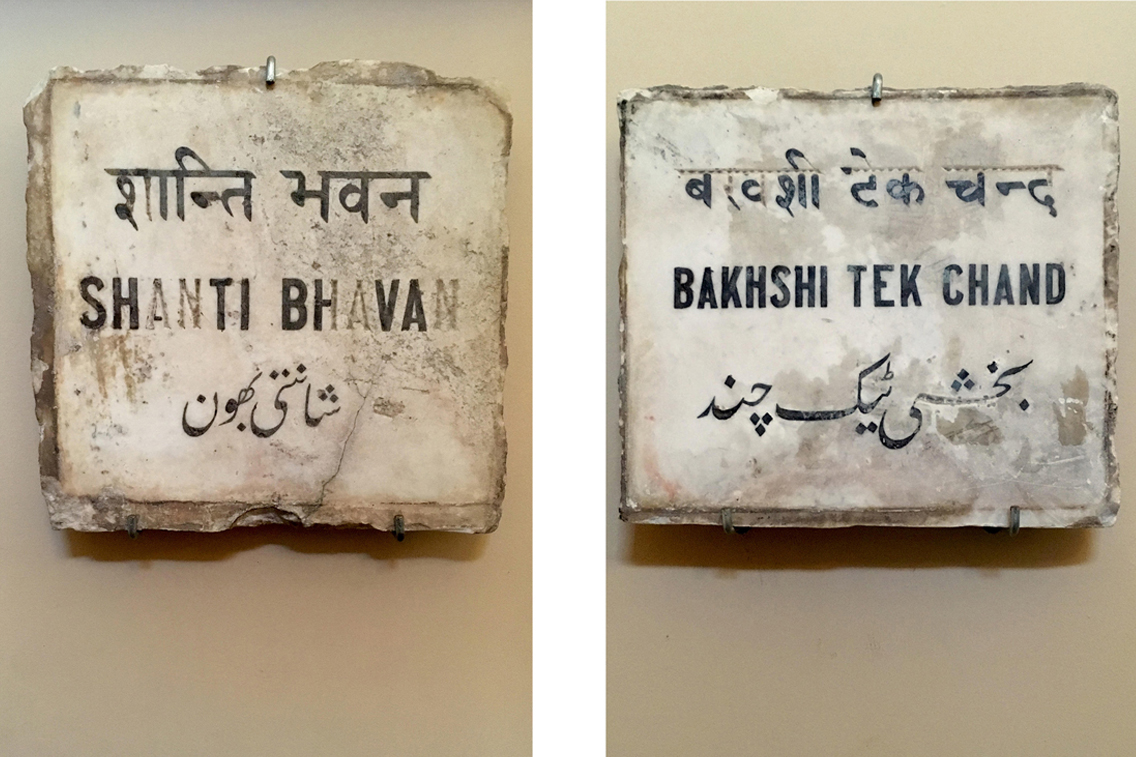

Plaques from Justice Bakhshi Tek Chand's home in Lahore, returned to the family in Delhi, decades after Partition

Idols carried by the family of Chunni Lal Malhotra from Sargodha to Gwalior. Read more

WAYS TO RETURN, WAYS TO HOLD ON

Remnants uses the aid of the migratory object to carve a pathway into the past. But through the course of my field research, I have learnt of many other nuanced ways in which people "return" to their homeland. Quite often, our interviews extended beyond the realm of the material, and into the sensorial and linguistic – how the refugee heart continues to hold onto the intangibles, as a way of returning to the Undivided land. How it is imprinted even within invisible things like the sound of a voice, the memory of a road, or the smell of the air, is something that is inevitably drawn out during these conversations.

Kalyani Ray Chowdhury, born in 1929, Chittagong, migrated to Calcutta and attempted to sow the plants she had grown up with. But nothing grew, for like people, even plants bear allegiance to their soil.

Balbir Singh Bir, born in 1938, Sillanwali, was led back home by language. Despite having lived in India for decades after Partition and learnt both Hindi and Punjabi, he still dreamt in his mother tongue of Urdu. Read more

GENERATIONAL MEMORY

Particularly remarkable have been those objects whose stories and memories have been unearthed and preserved not by their original owners, but by their offspring – second and third generation inheritors of Partition’s lingering trauma; children and grandchildren who sat in on and participated in many of the interviews described here, both asking and answering questions. This goes only goes to demonstrate that until there continues to be a generational impact from the event, there will continue to be an accumulation and excavation of its memory, both lived and inherited.

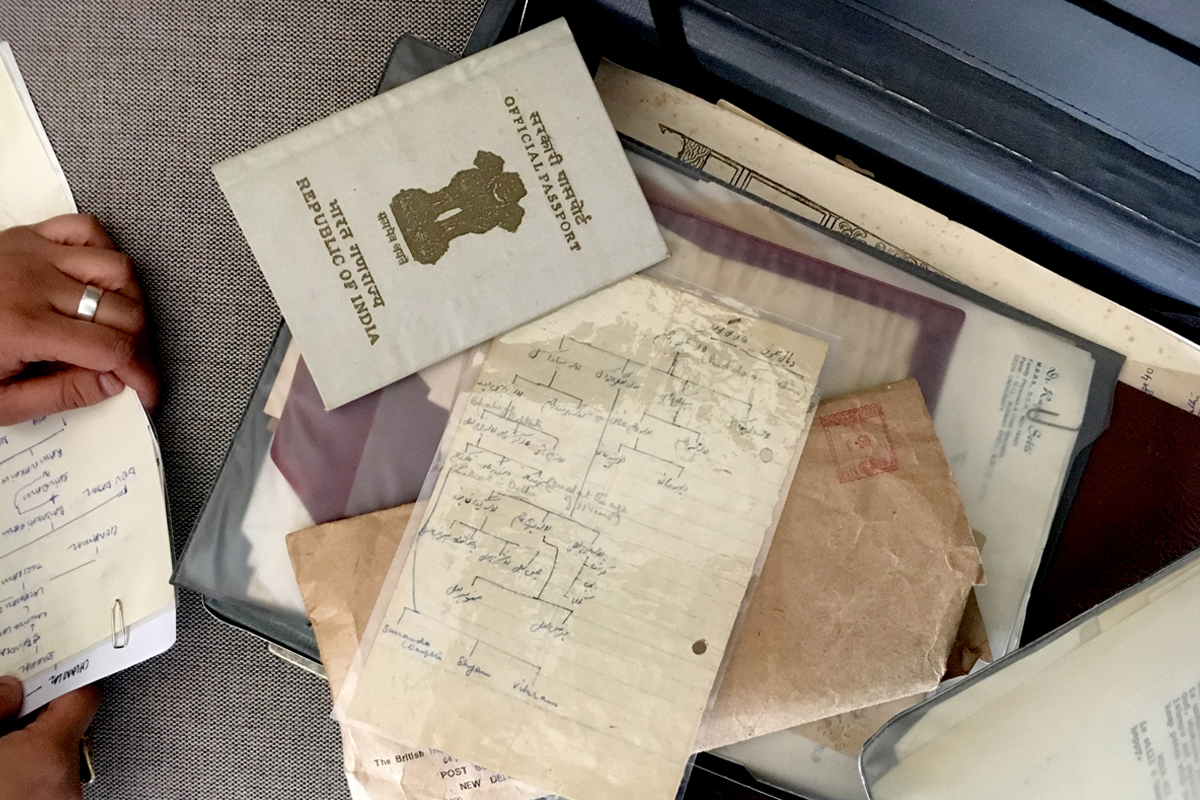

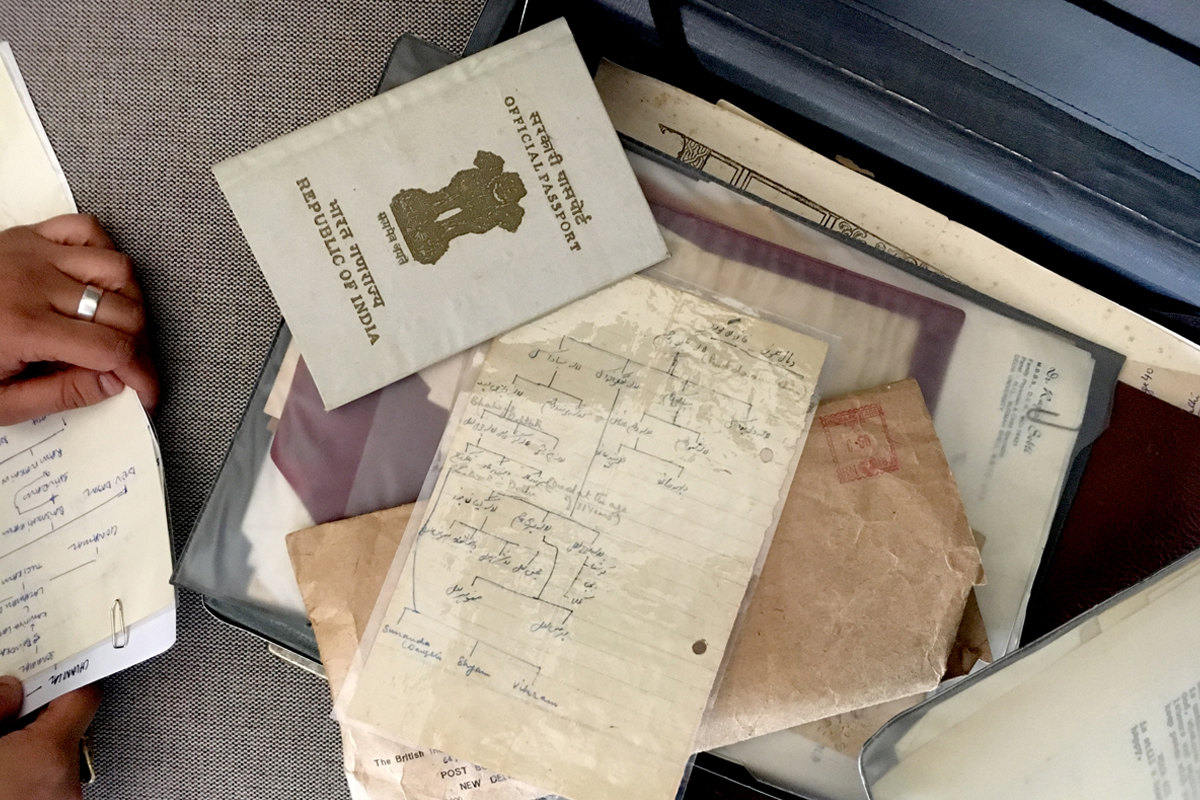

Briefcase belonging to Navdha Malhotra's gradfather. On the top, it reads, 'With best compliments from New Bank of India Limited’, a pre-Partition establishment in Lahore. Read more

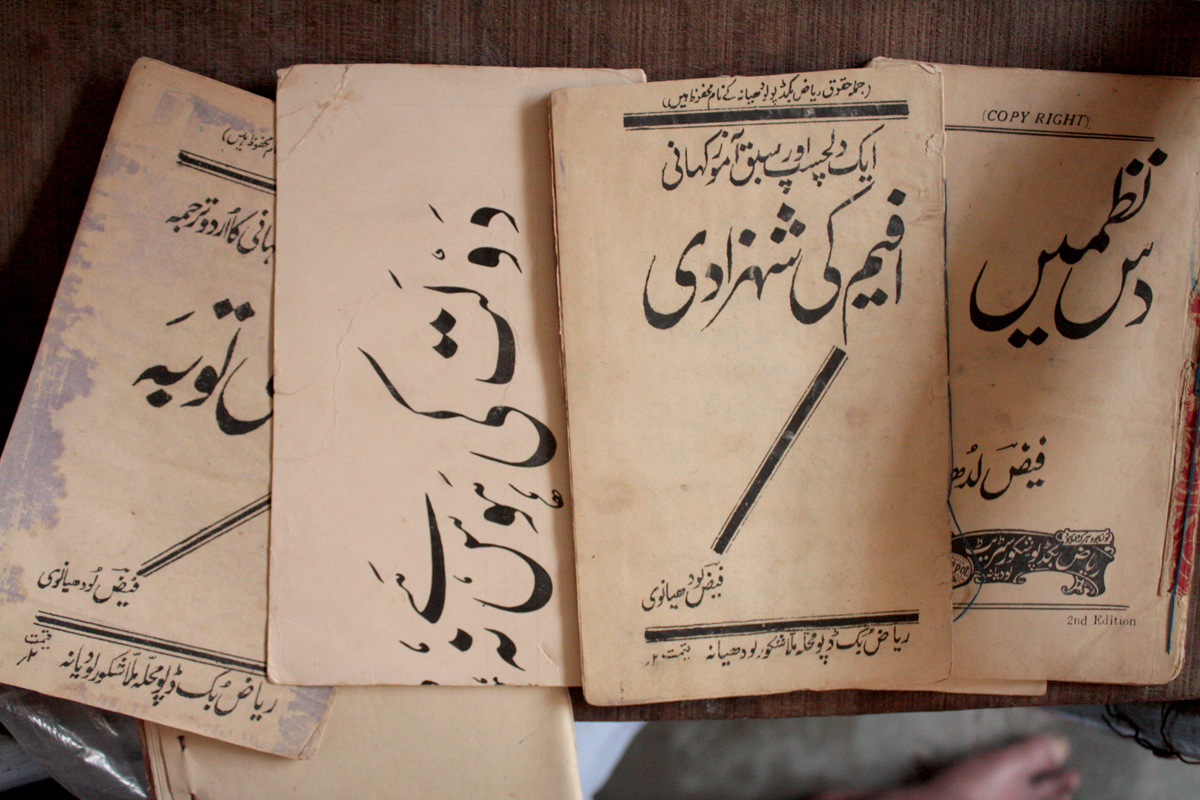

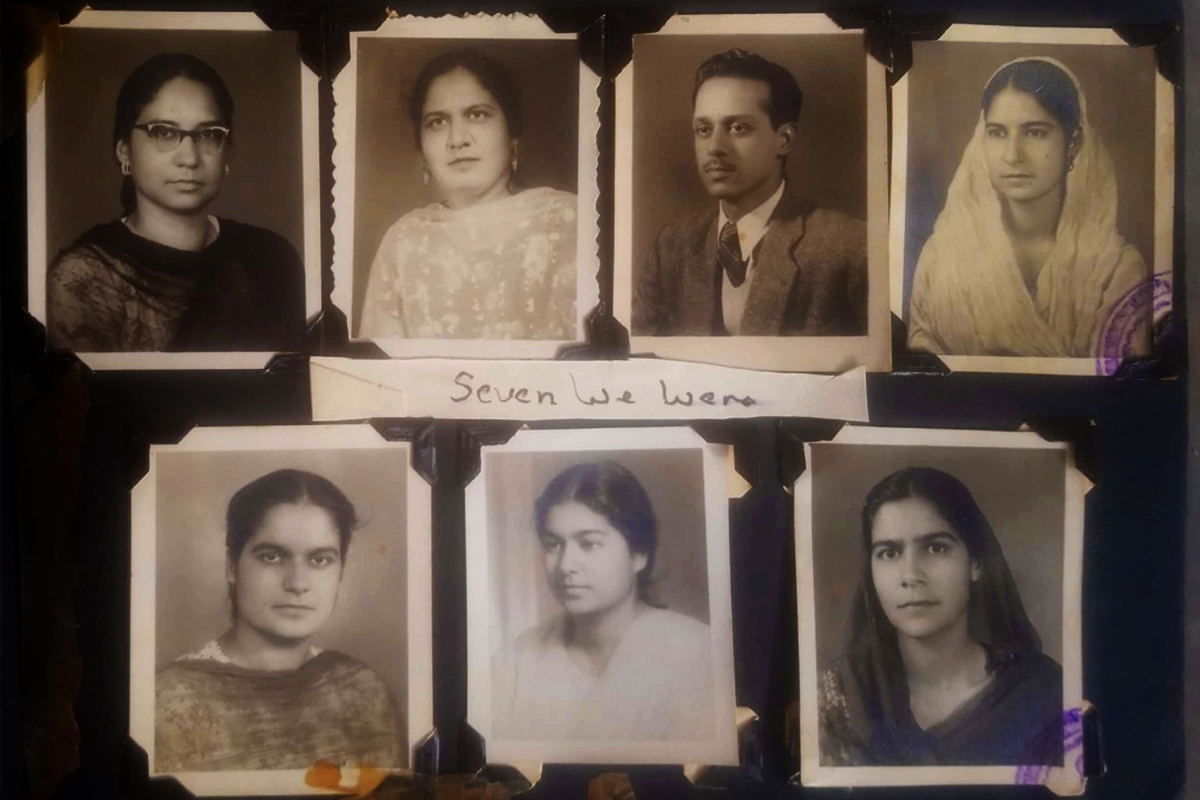

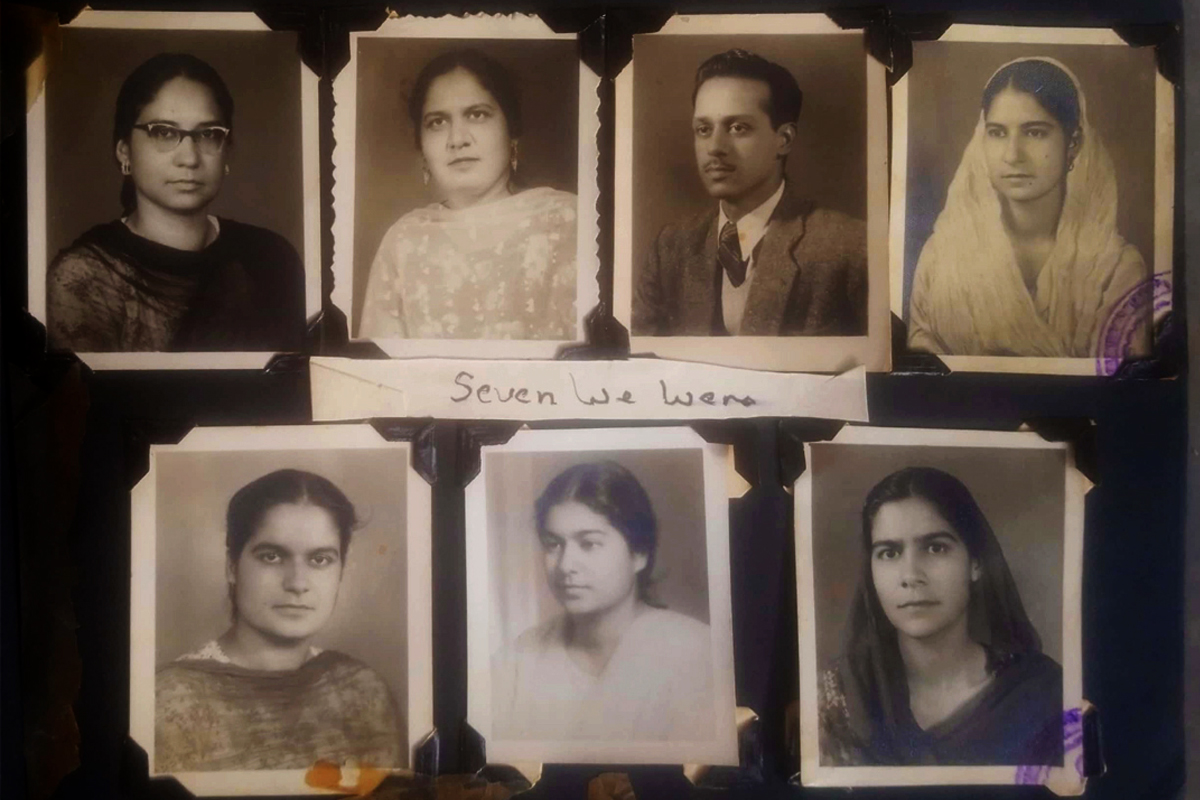

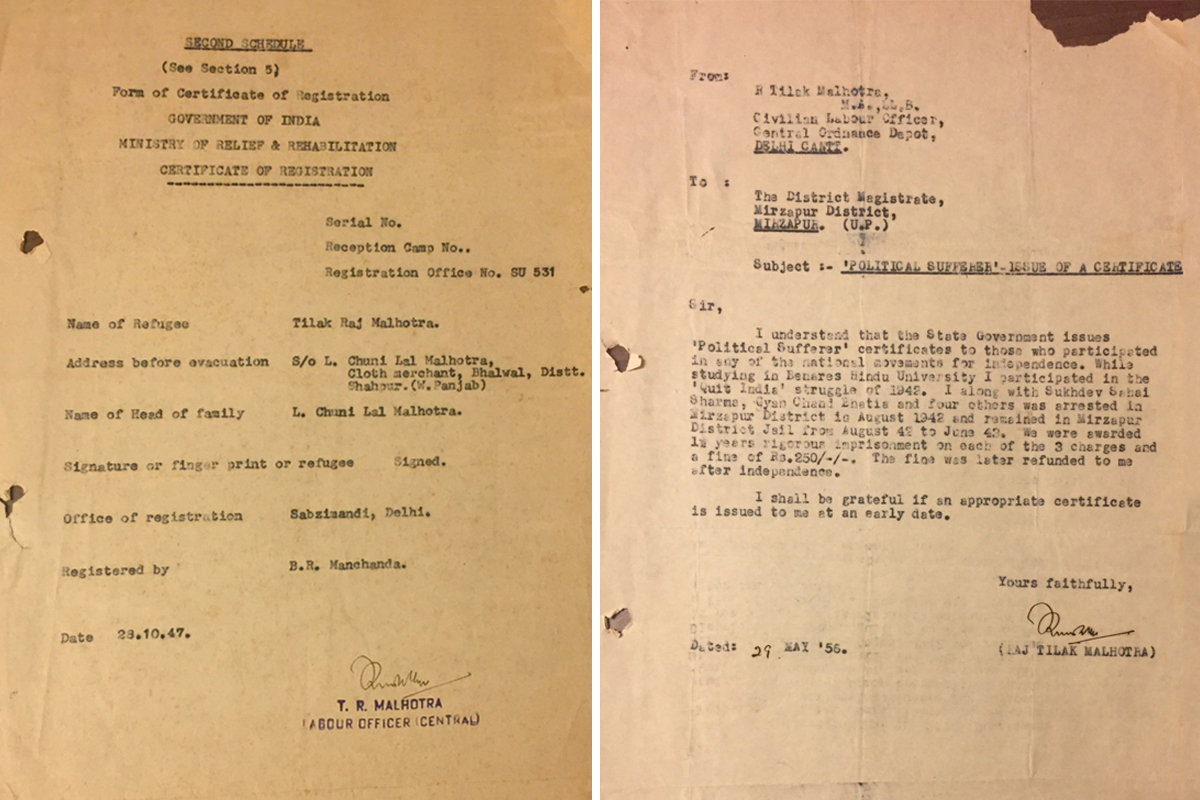

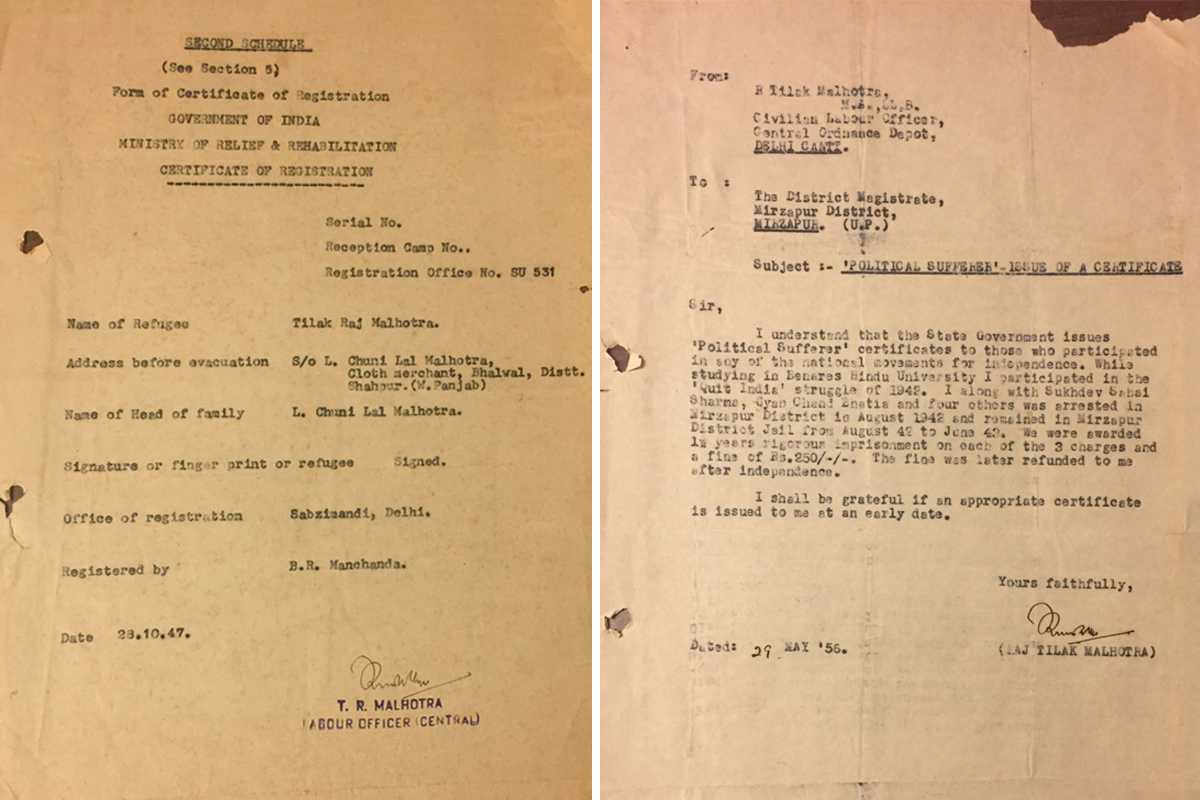

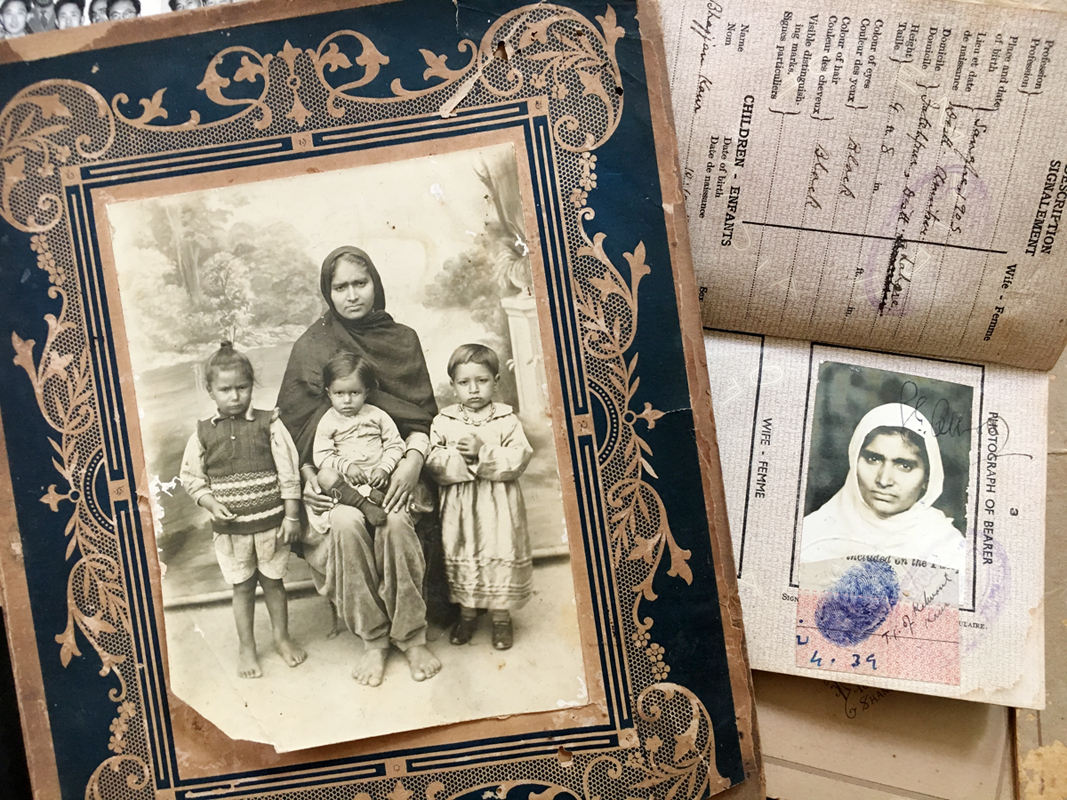

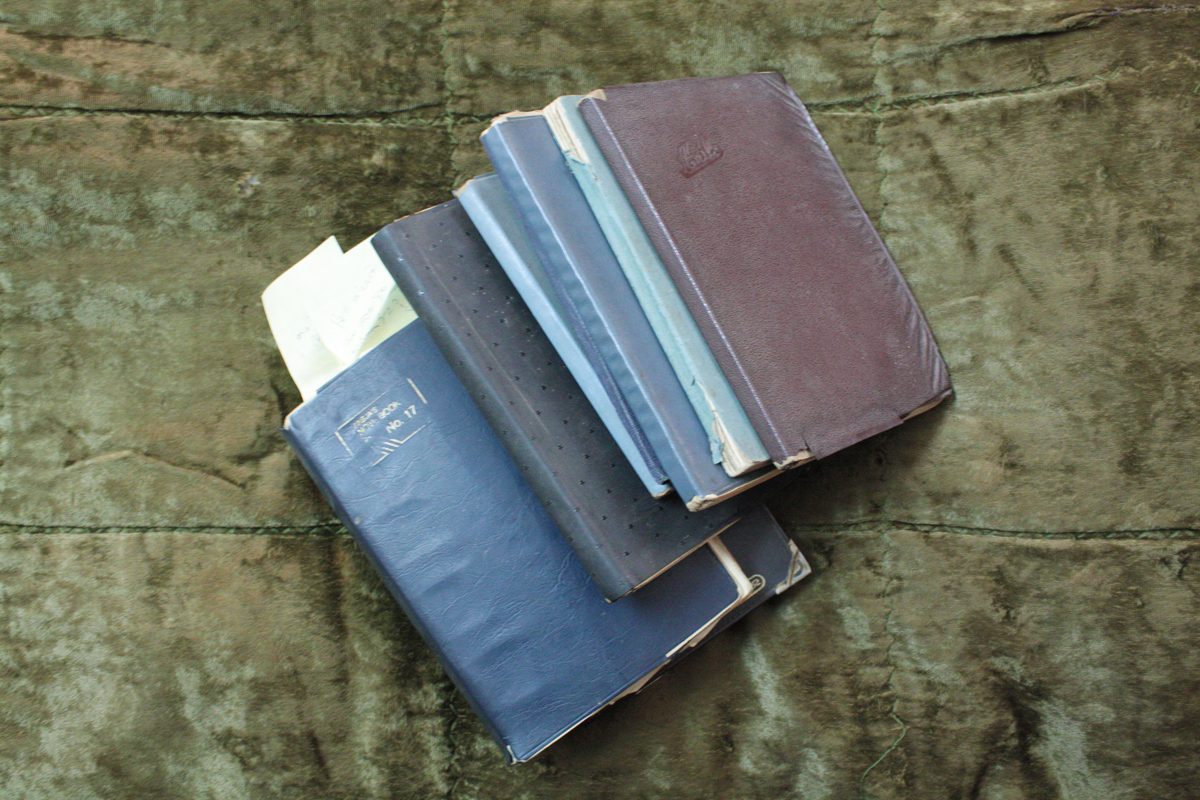

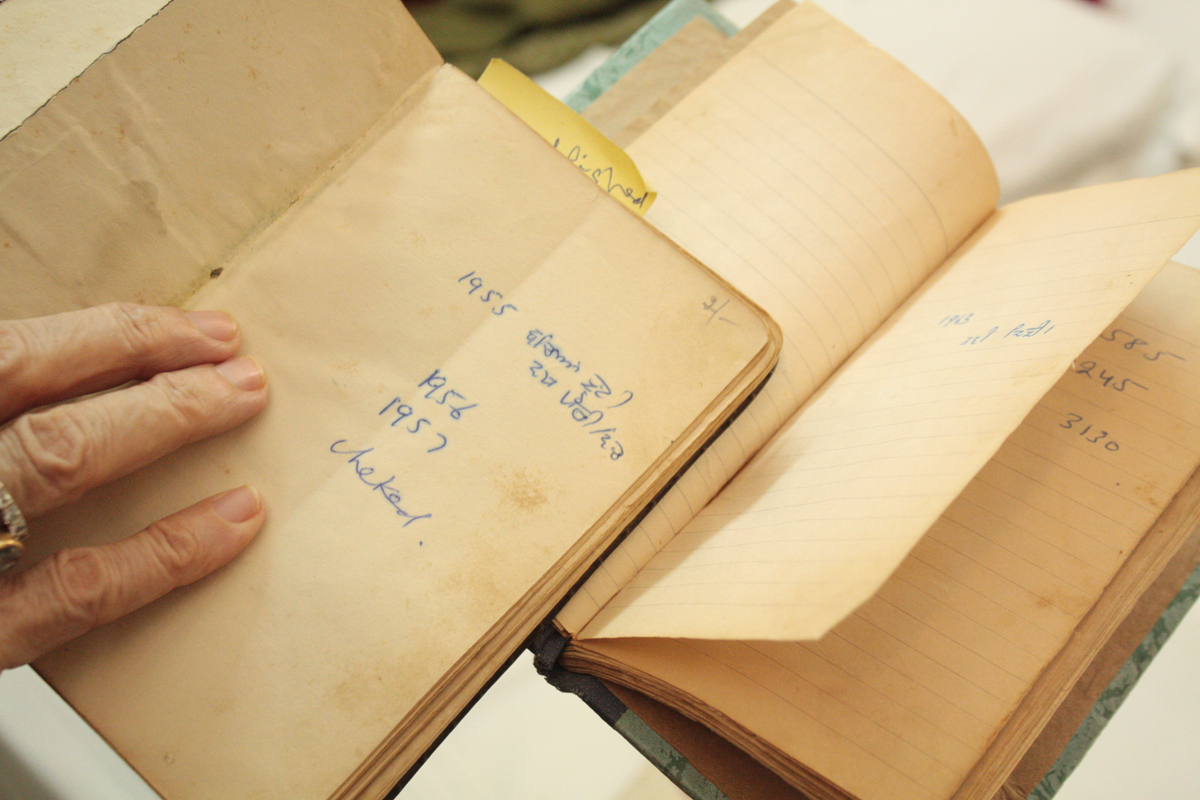

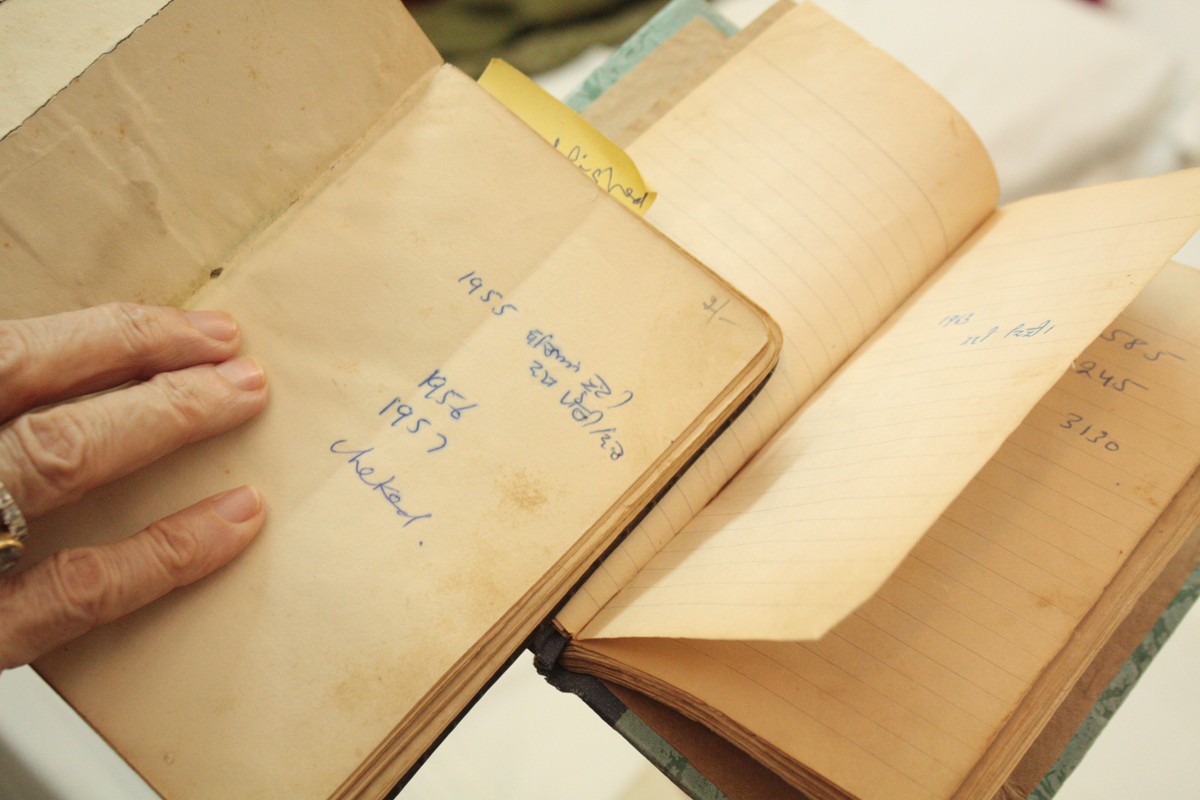

The contents of Tilak Raj Malhotra's briefcase include journals, official papers, education certificates, letters, a passport, a family tree and pension documents.

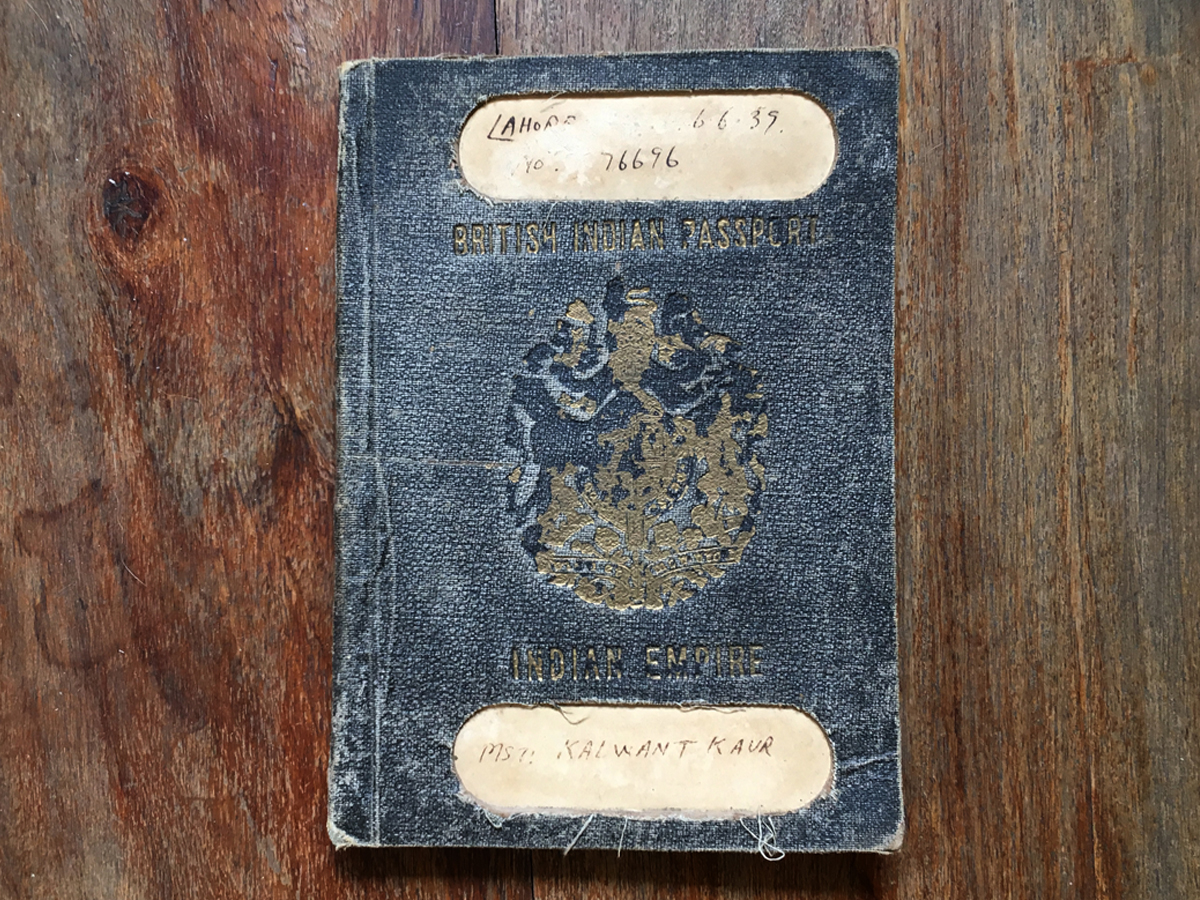

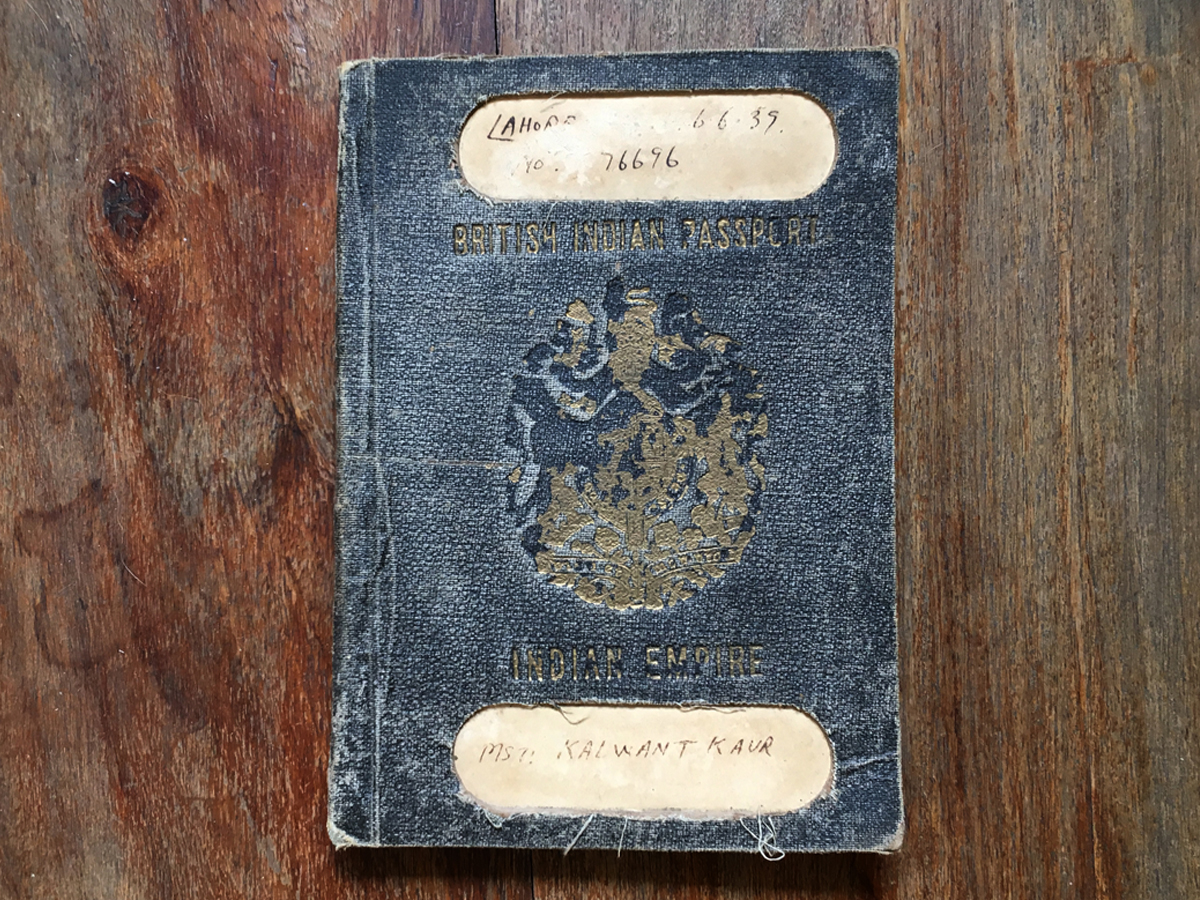

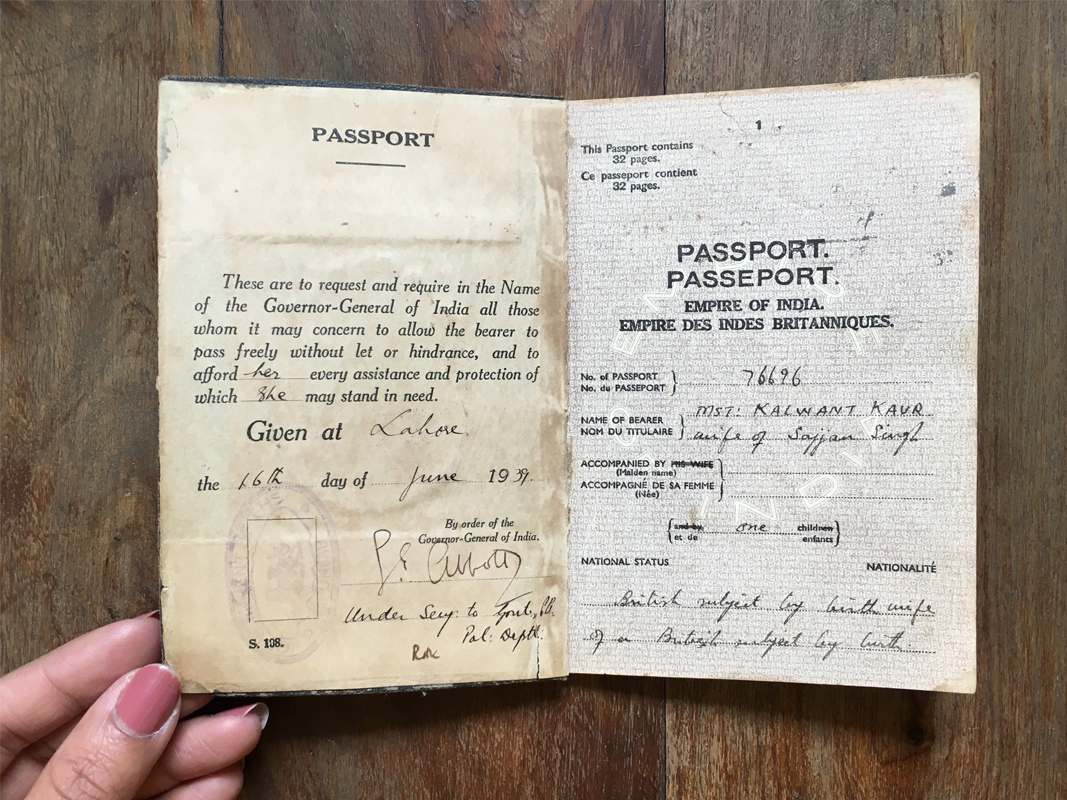

The first page of the passport which states that she is a 'British subject by birth. Wife of a British subject by birth'

A photograph of Mrs. Kulwant Kaur and her passport, now in possession of her great granddaughter, Amita Bal. Read more

A SINGLE LINE, A SINGLE WORD

There is a distinct weight to the utterance of the word 'Partition'. In my family a word unspoken for years, a feeling unexplored, a wound untouched. Partition. I listen to my lips release it into the world and ponder on its lingering aftertaste. The very weight of the word, the way it sounds as I say it out loud, how I enunciate its every syllable with clarity and care in a way that has been subconsciously ingrained in me. How I use it with an almost extreme fragility, considering at all times its innate heaviness in the context of the Indian subcontinent – what it means to be Indian, to be Pakistani and, later, to be Bangladeshi. The entire concept of a cultural identity enveloped within a single event, a single line, a single word: Partition.

BOOK CHAPTERS

A GAZ FOR MY FATHER AND A GHARA FOR MY MOTHER : THE HEIRLOOMS OF Y. P VIJ

Y.P Vij, b. 1930 Lahore, holding the gaz his father carried to Amritsar. Read more

GIFT FROM A MAHARAJA : THE PEARLS OF AZRA HAQ

UTENSILS FOR SURVIVAL : THE KITCHENWARE OF BALRAJ BAHRI

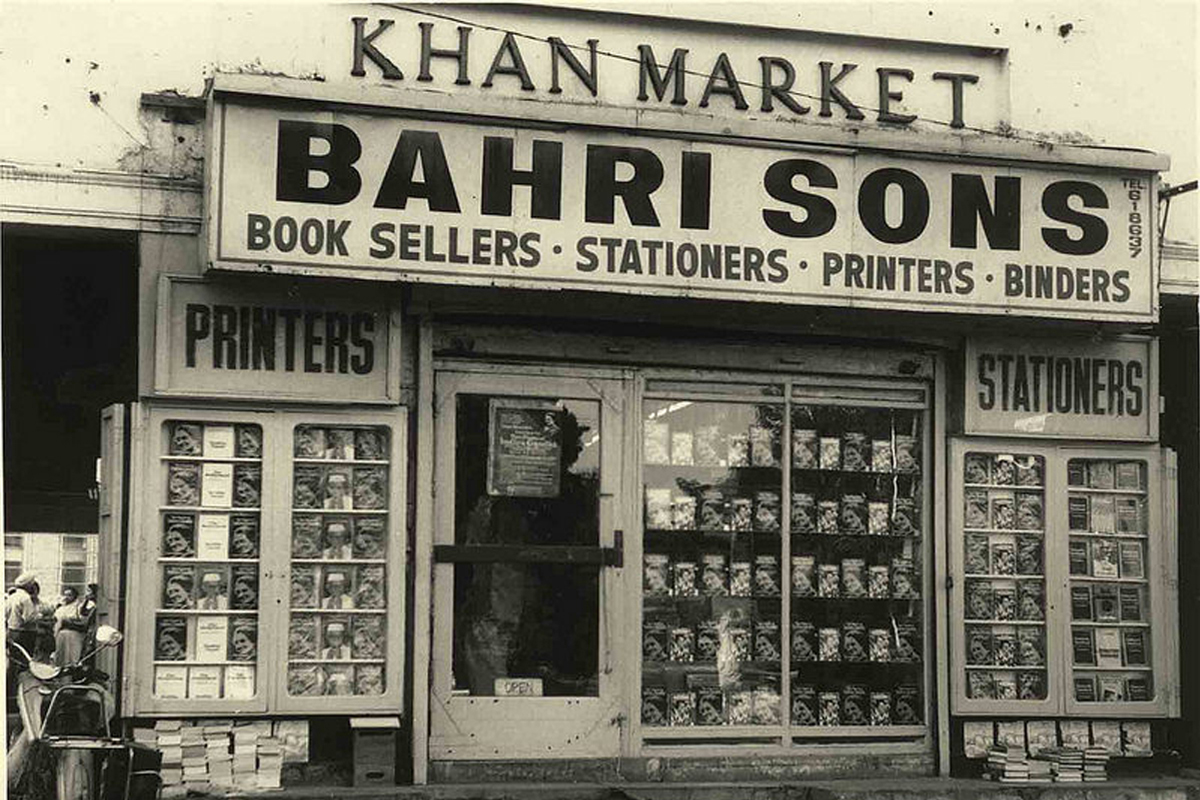

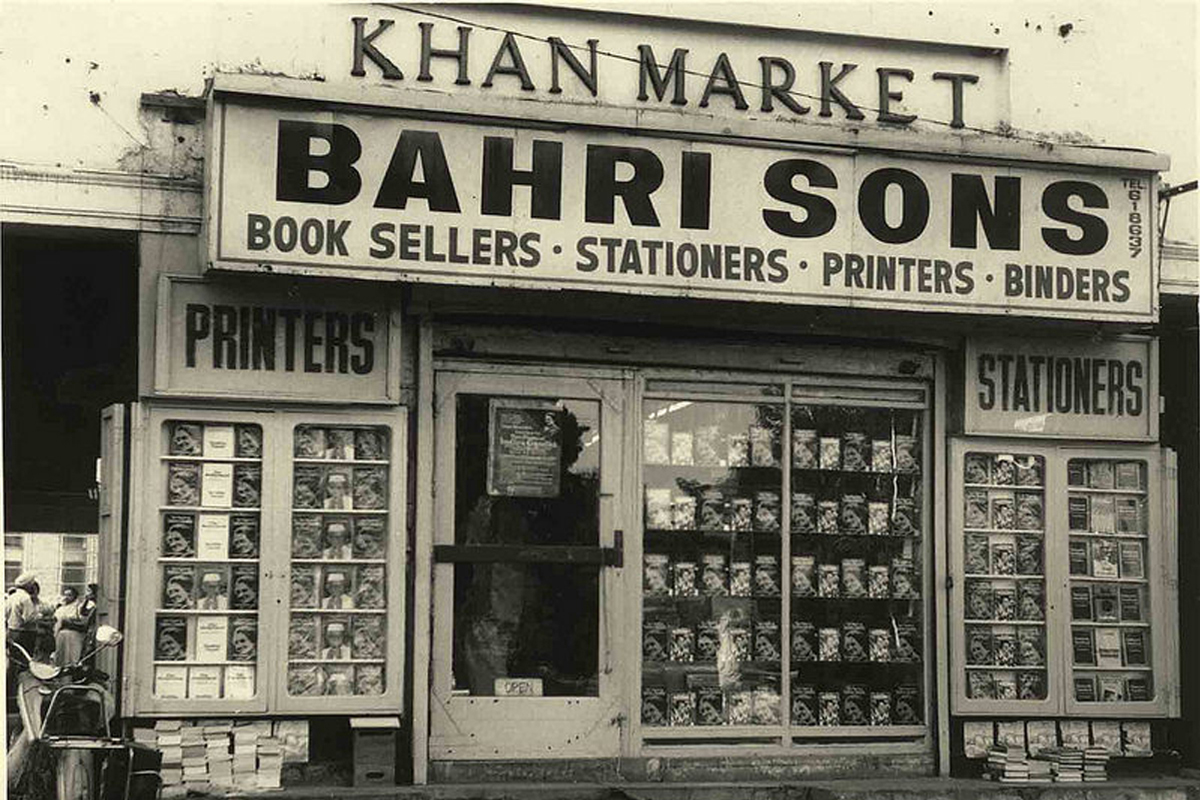

Bahrisons, set up in 1953, Khan Market, Delhi. Read more

The Kade-wala glass used to drink water at the station in Amritsar city, where the family stayed in a camp before arriving in Delhi. The rim is engraved with the initials D.L.M

A plate with the initials B.M, Balraj Malhotra, is one of the few engraved utensils that remains from the family home in Malakwal, district Gujrat, West Punjab

Utensils the family carried and used in the makeshift camp in the cotton factory in Malakwal, and then during their years-long stay in the Kingsway Refugee Camp in Delhi. Read more

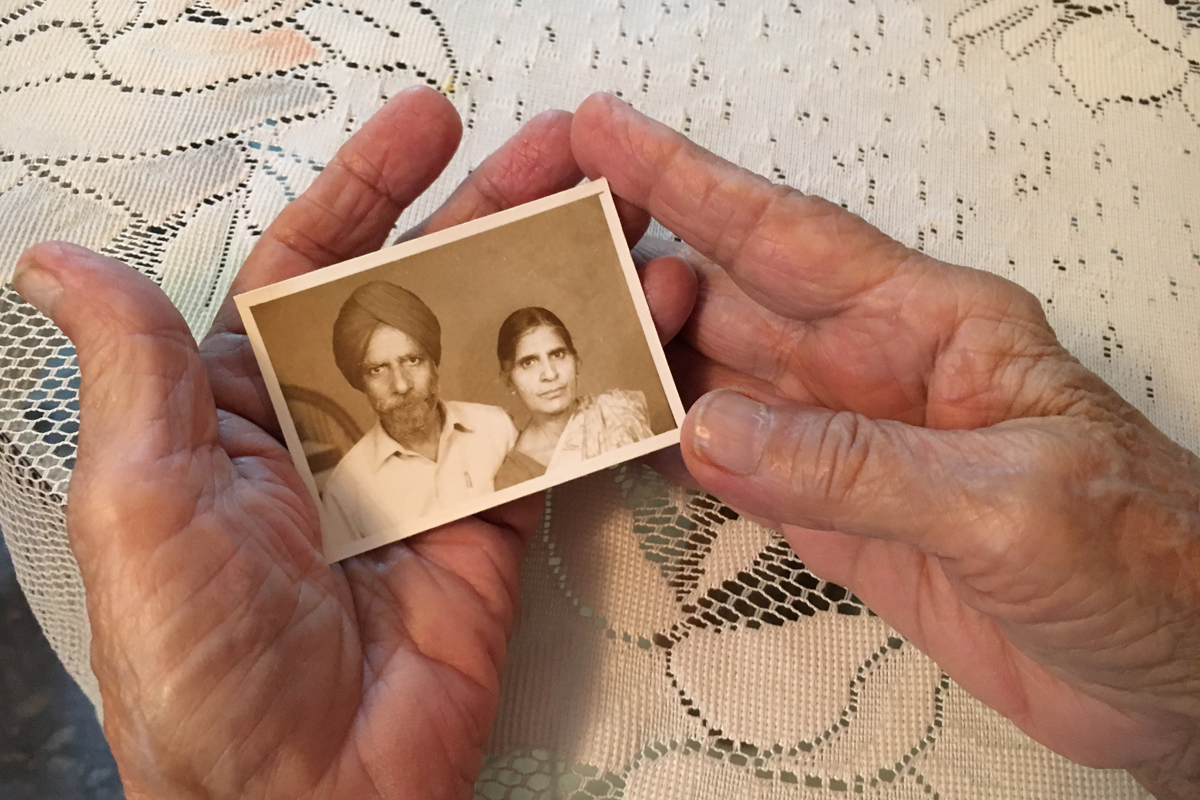

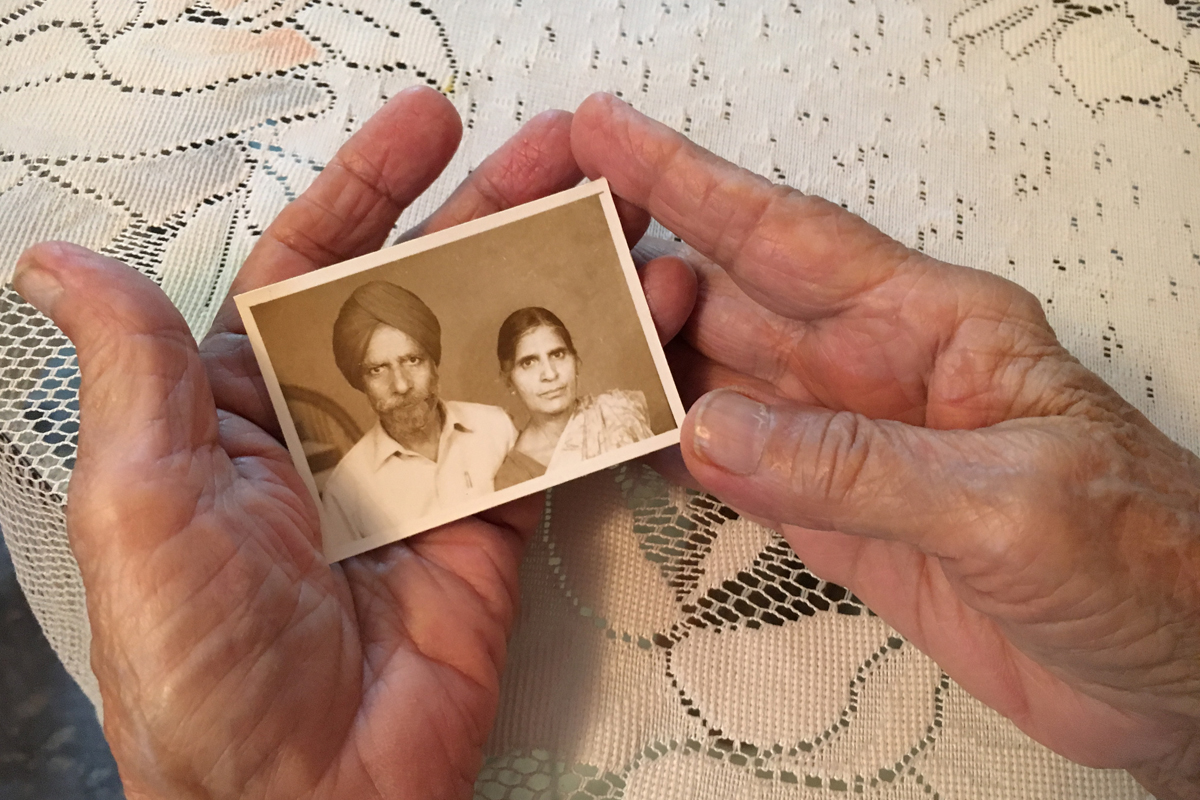

STONES FROM MY SOIL : THE MAANG-TIKKA OF BHAG MALHOTRA

The foldable pocketknife made of ivory, given to Bhag Gulyani for her protection. Read more

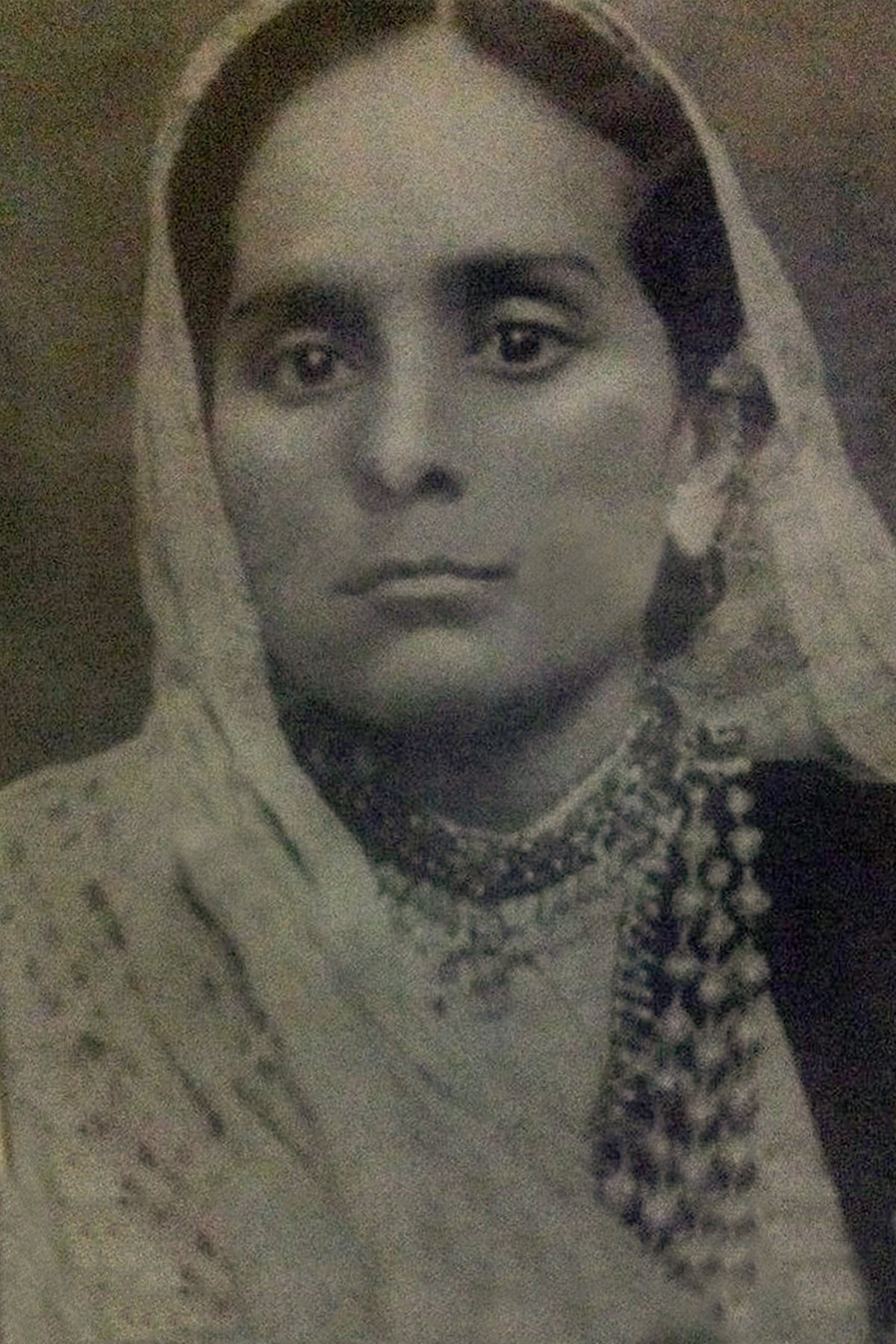

Bhag Malhotra (née Gulyani) b. 1932 Muryali, D.I Khan, wearing the maang-tikka her mother, Lajvanti Gulyani to Delhi

THE DIALECT OF STITCHES AND SECRETS : THE BAGH OF HANSLA CHOWDHARY

Hansla Chowdhary, wearing the heirloom textile she inherited from her maternal grandmother, Gobind Kaur, the youngest of Sardarni Sunder Kaur's children. Read more

The chevron pattern spread across the length of the Phulkari bagh in yellow and orange silk threads, on a base of rough Khadi panels stitched together.

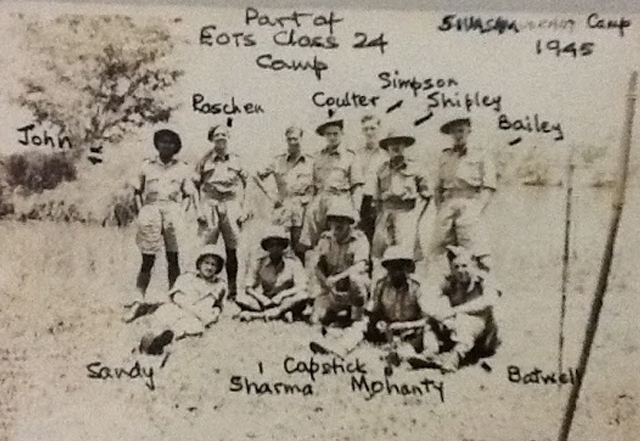

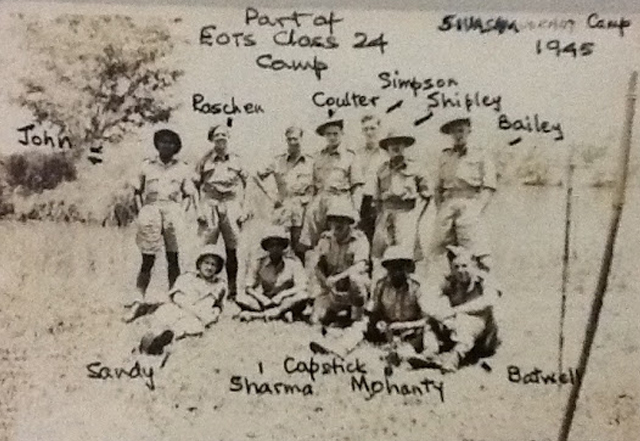

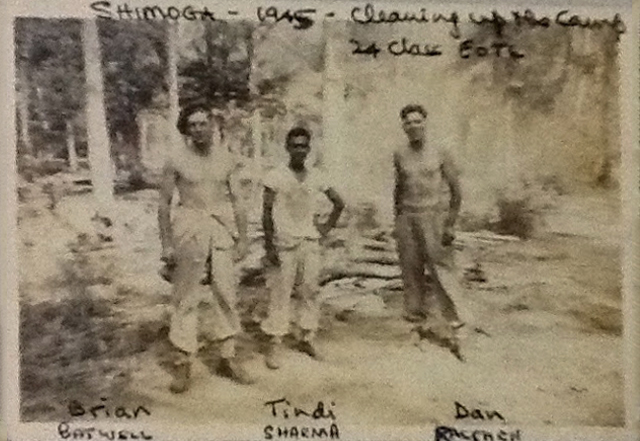

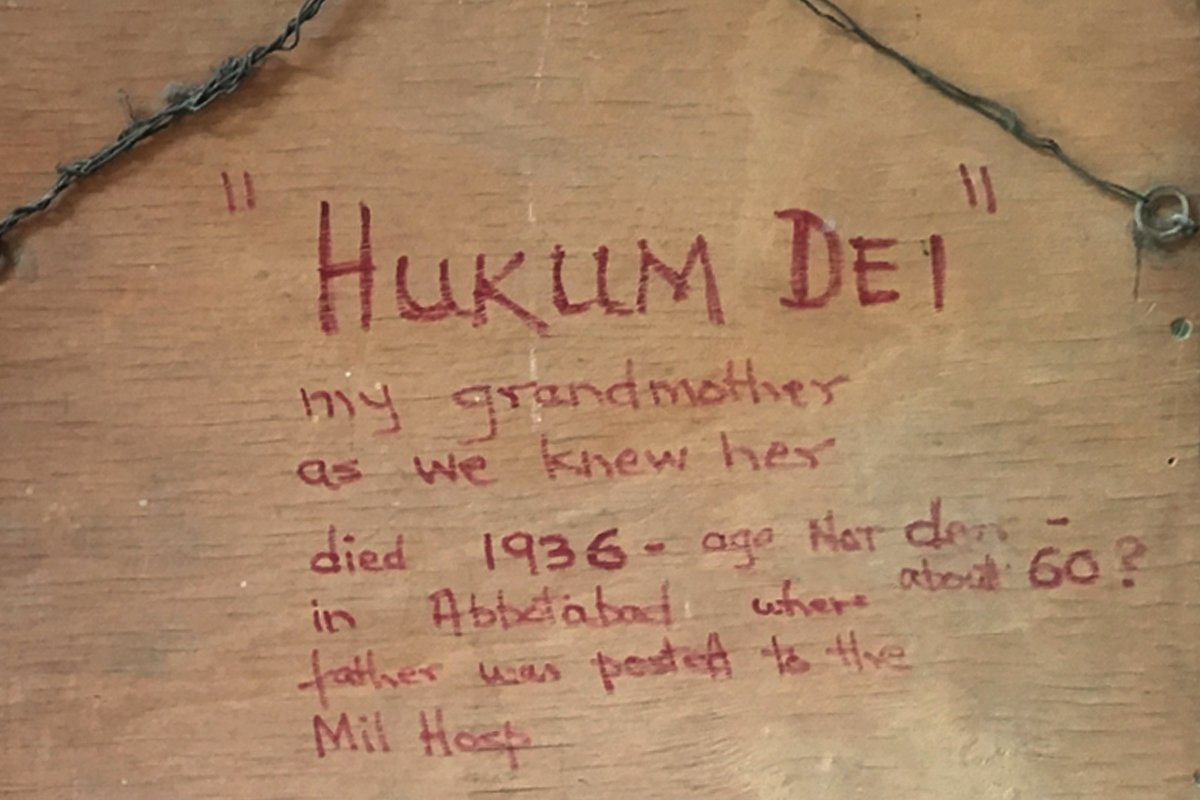

HEREDITARY KEEPERS OF THE RAJ : THE ENDURING MEMORIES OF JOHN GRIGOR TAYLOR

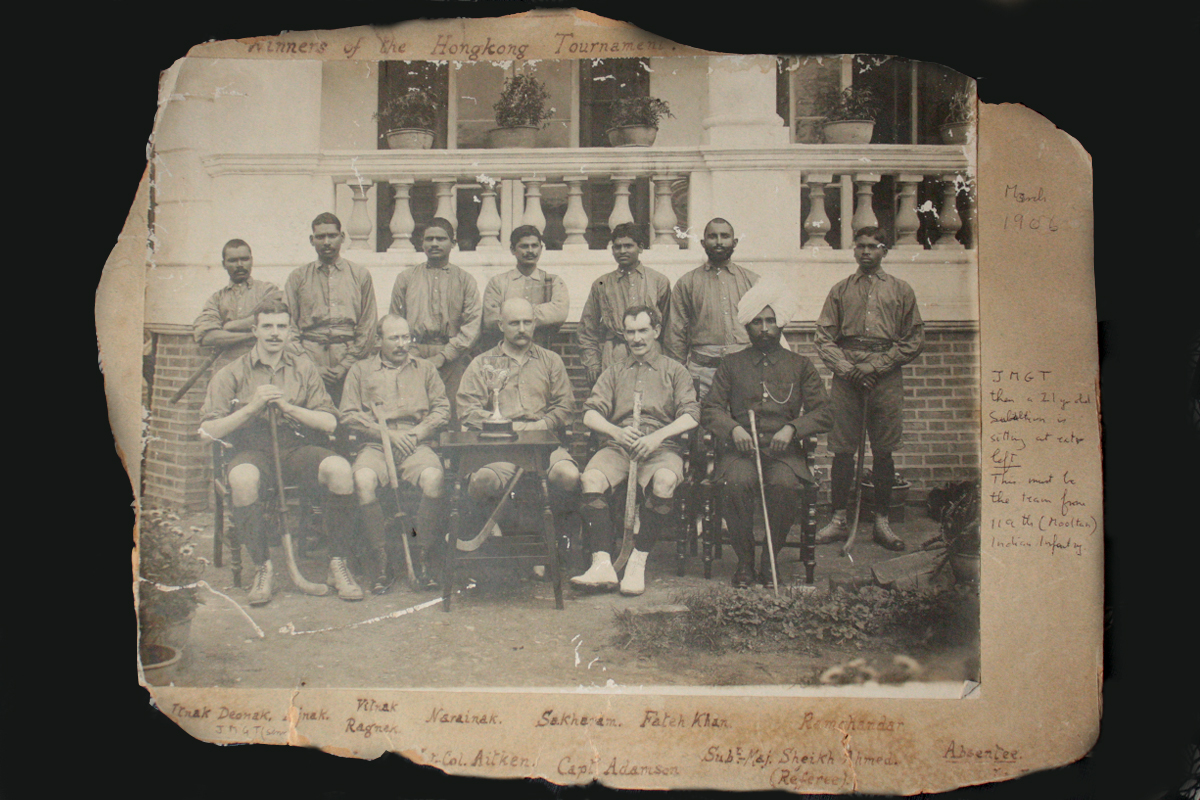

Photograph of John McLeold Grigor Taylor, with the inspcription - "JMGT, then a 21 year old, is sitting at the ext. left. This must be from 119th (Mooltan) Indian Infantry."

"JGT with his father at the Fort DERA Ismail Khan, NW Frontier." Both John Grigor Taylor and his father would serve in the Rajputana Rifles of the Indian Army.

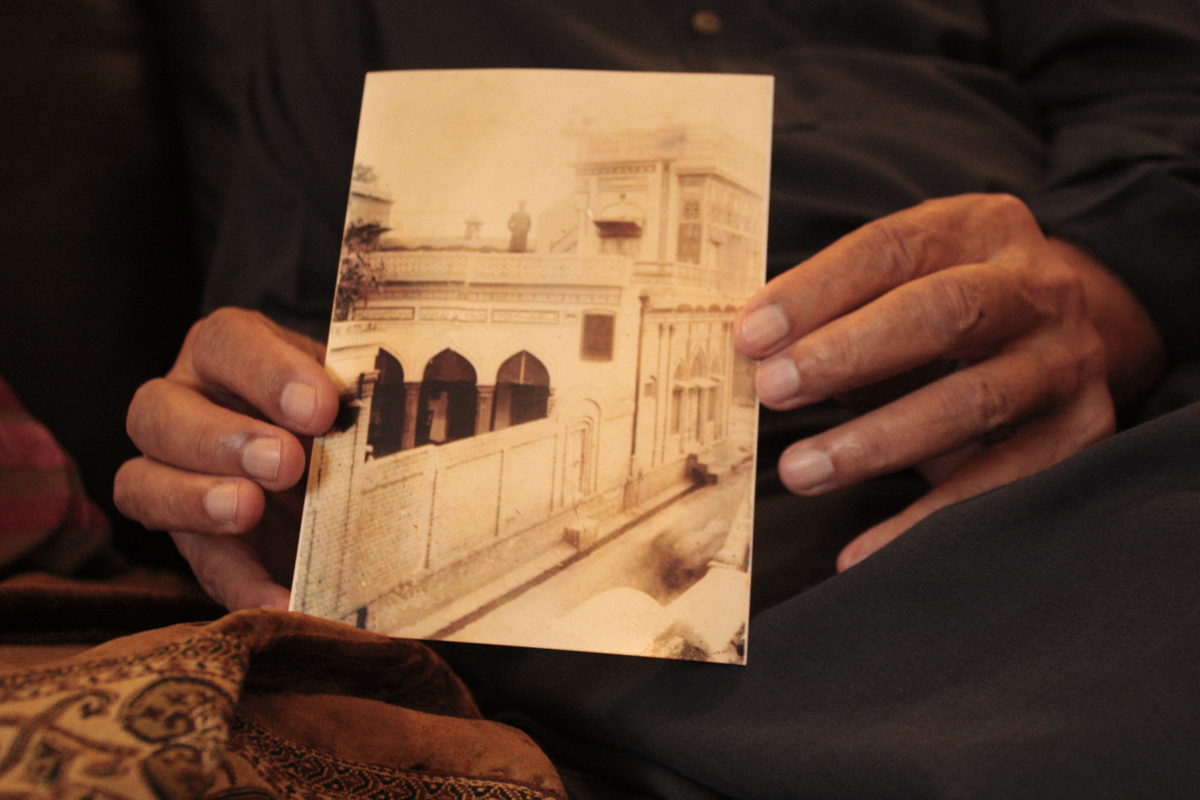

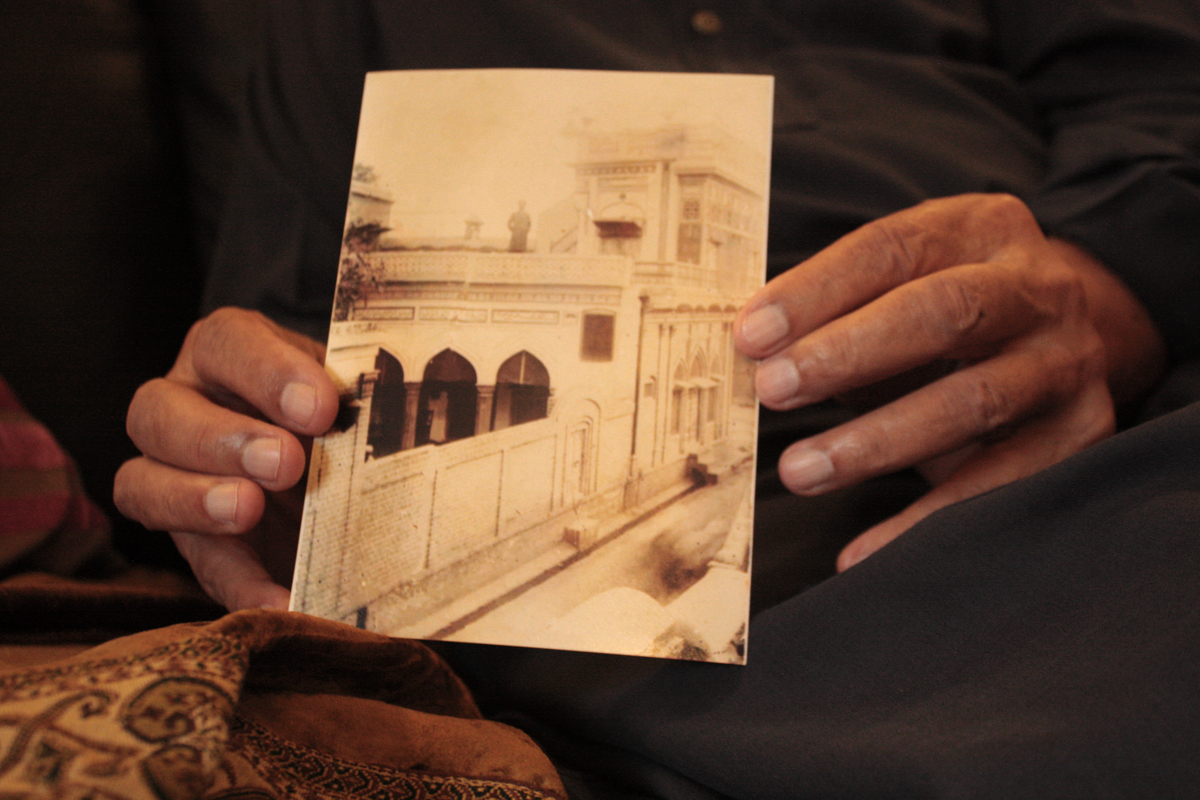

THE LIGHT OF A HOUSE THAT STANDS NO MORE : THE STONE PLAQUE OF MIAN FAIZ RABBANI

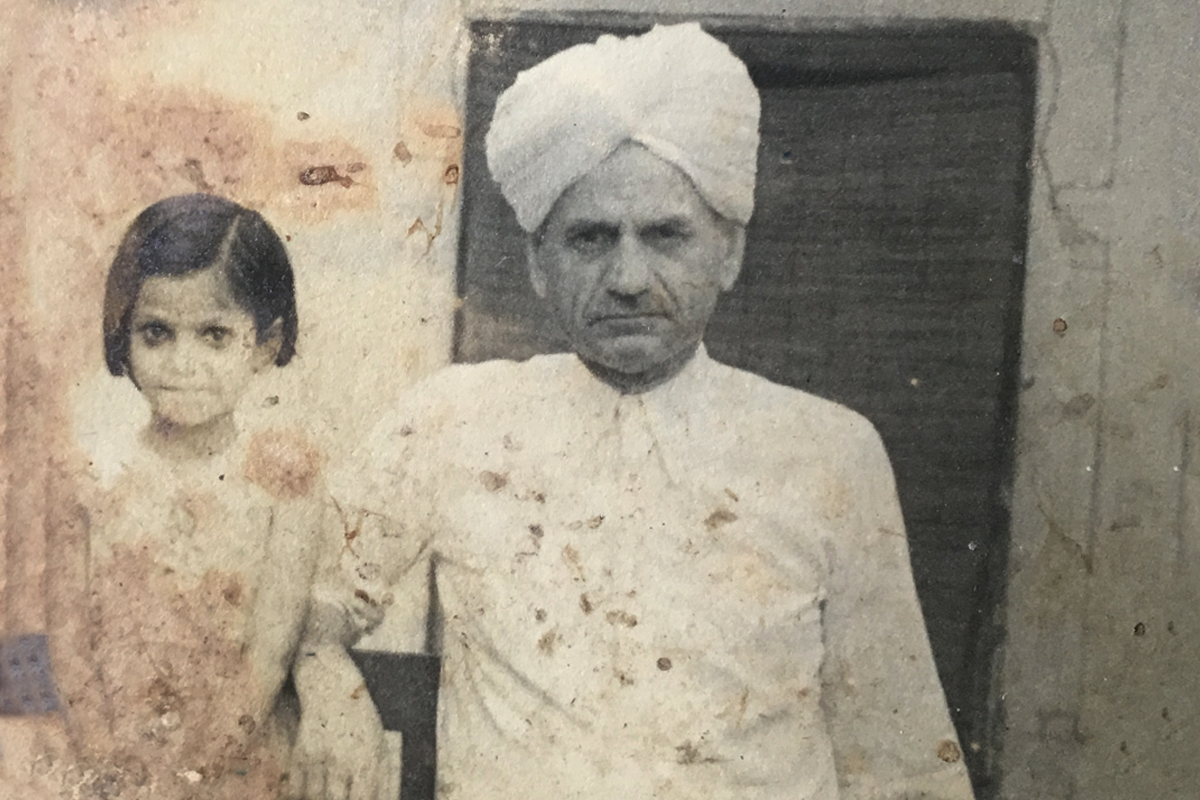

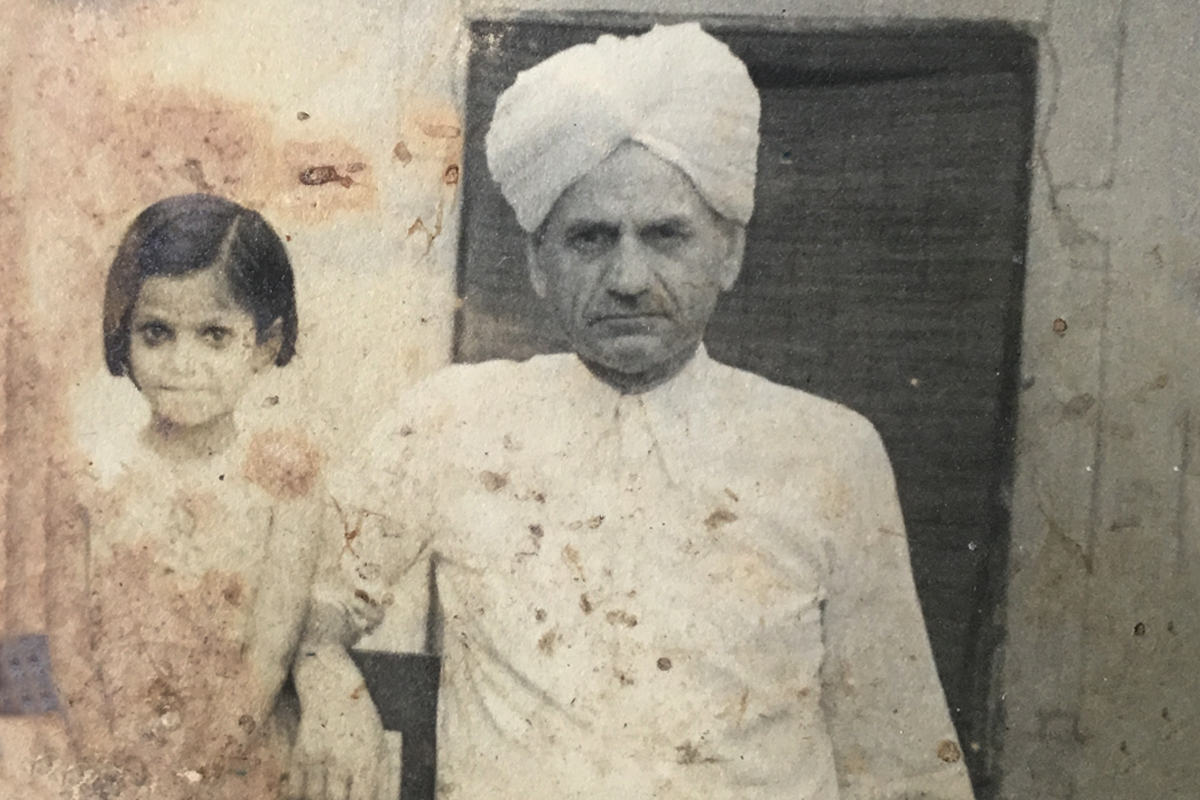

A photograph of Shams Manzil showing Rabbani sahib's father, Mian Rehmat-ullah, the Municipal Commissioner of Jalandhar for two tenures. He died in 1935, soon after this photo was taken. Read more

THE INHERITANCE OF CEREMONIAL SERVINGS : THE KHAAS DAAN OF NARJIS KHATUN

Narjis Khatun, b. 1937, Patiala, on the first day of sawan, and migrated to Alipur via Samana and Multan. Read more

The Khaas-daan, cast in bronze and resembling a french cloche, was used to serve paan to a special or khaas guest. It was once a standard inclusion in every bride's trousseau, and the art of making paan was a quality of delicacy. Read more

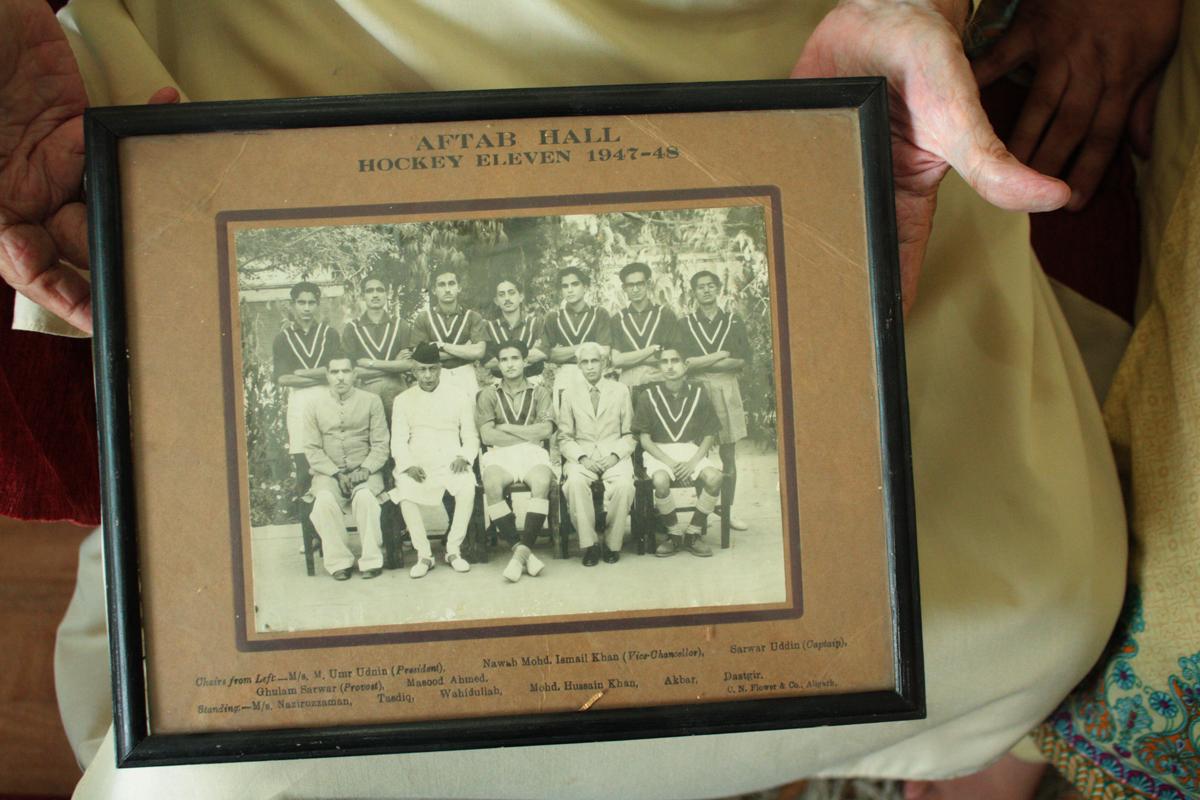

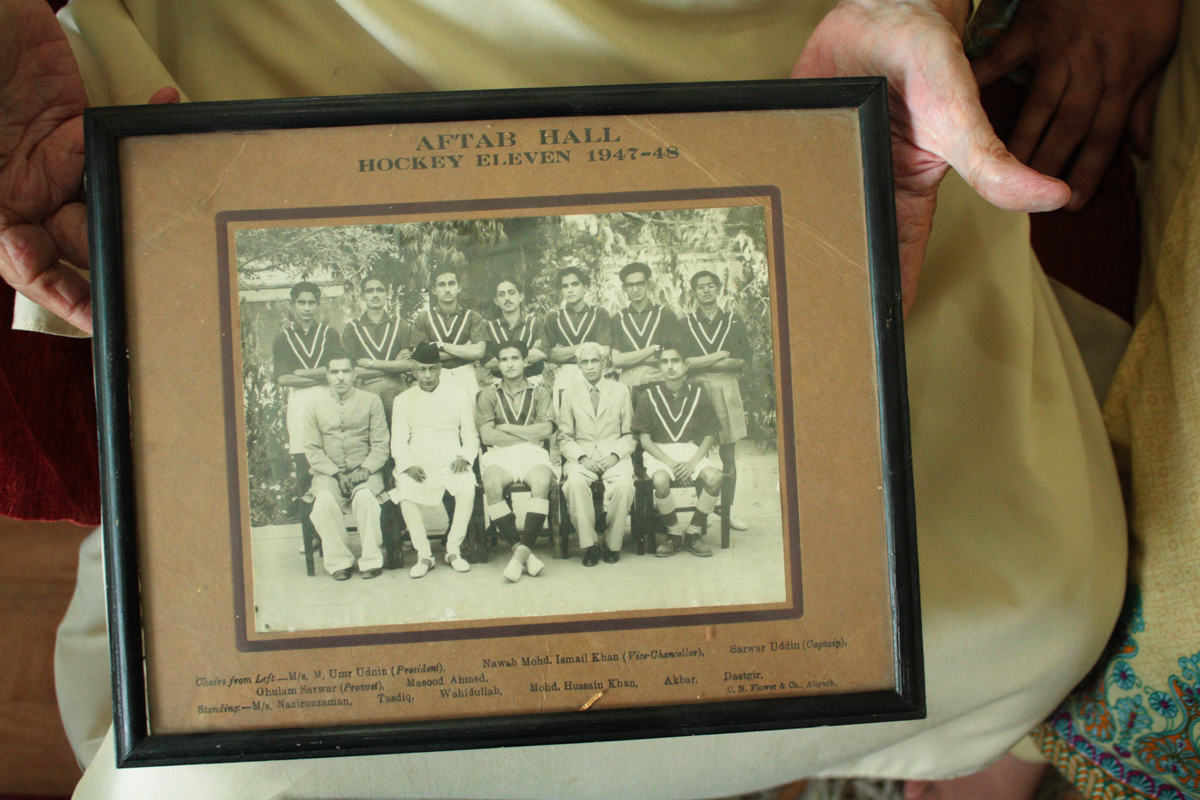

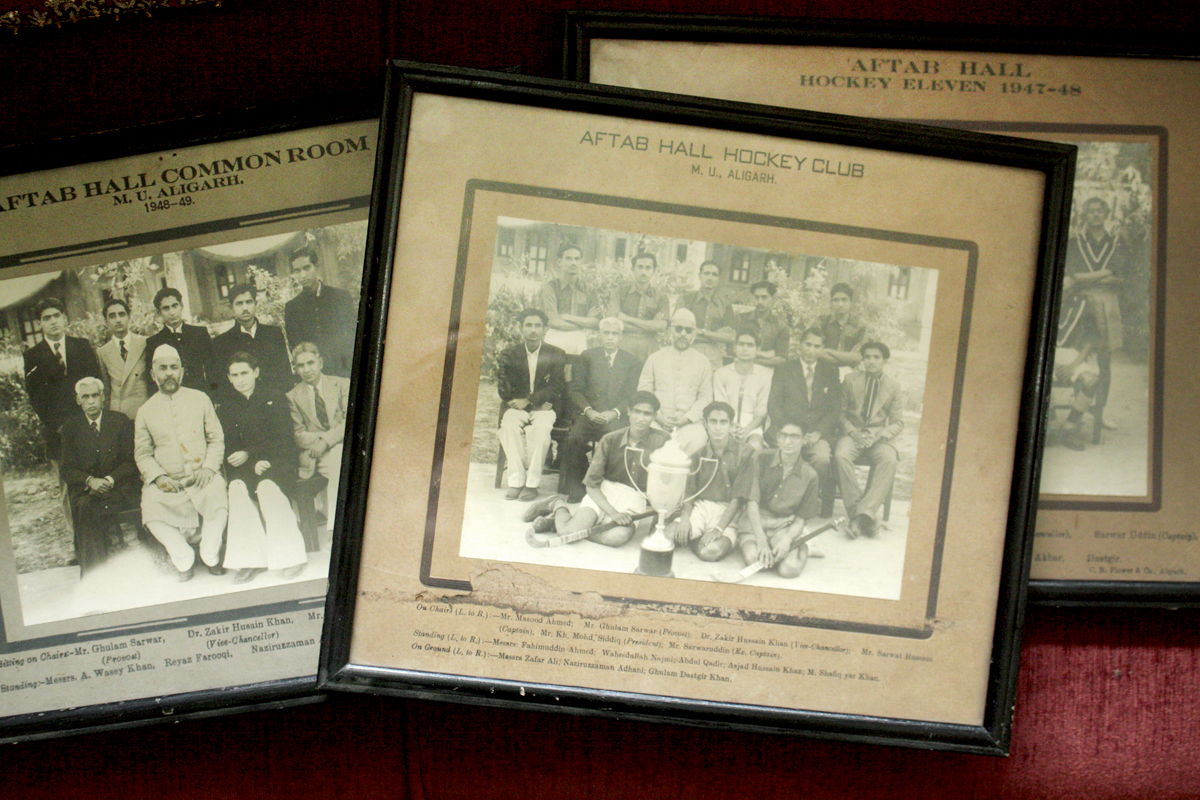

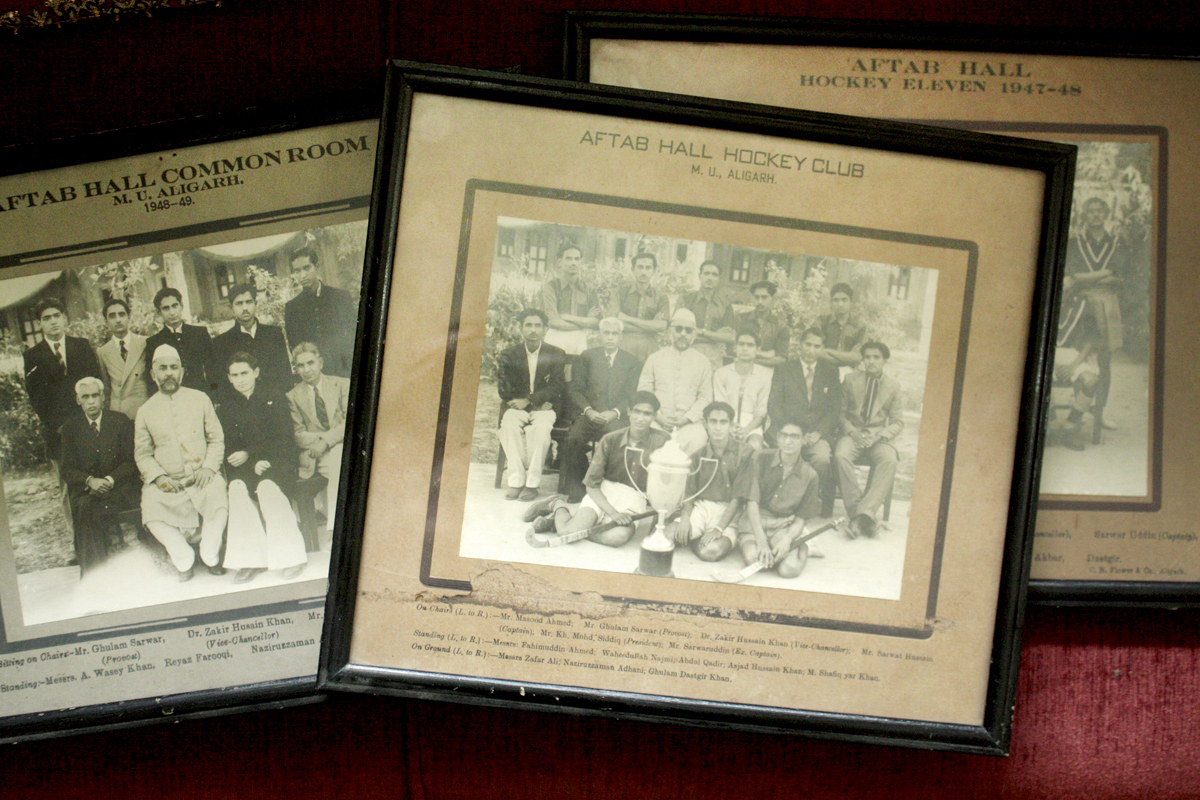

THE HOCKEY FIELD I LEFT BEHIND : THE PHOTOGRAPHS OF NAZEER ADHAMI

Nazeer Adhami, born 1930 in Hardoi, United Provinces and migrated to Karachi in 1953. Read more

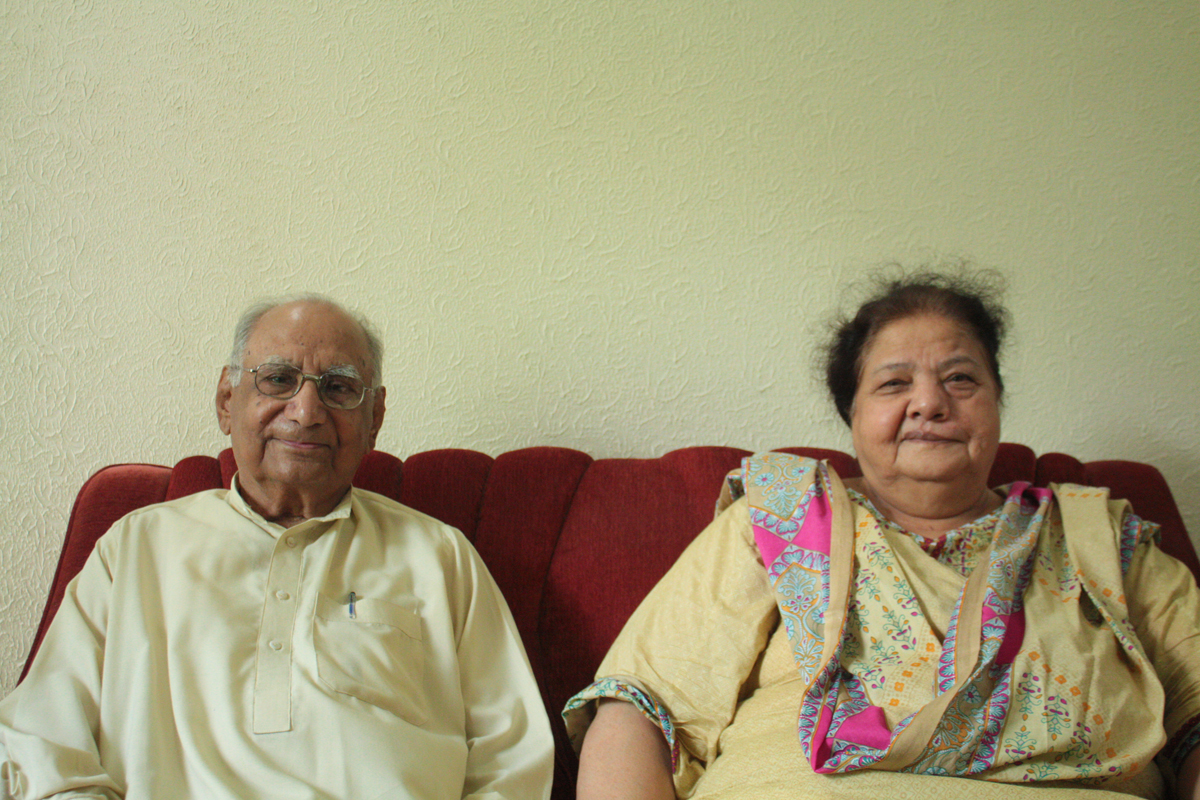

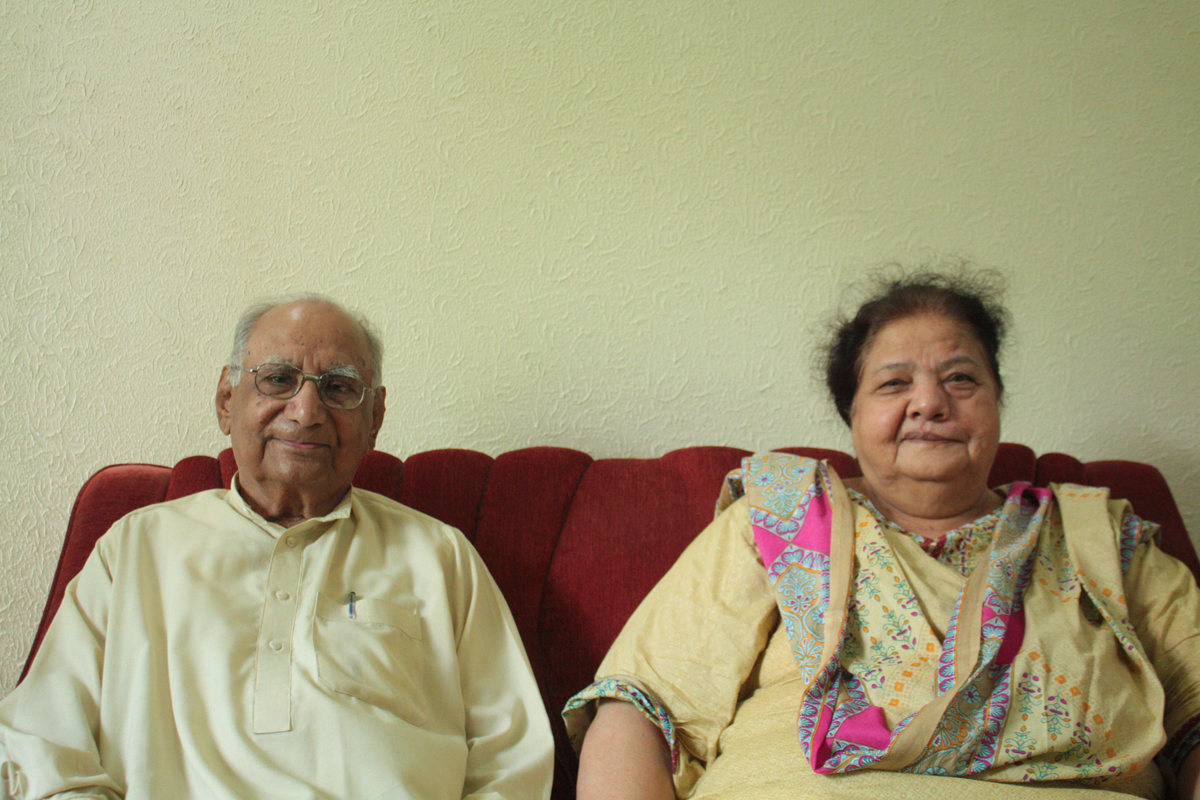

With his wife, Najma Nazeer in their Lahore home, 2014. Najmi ji, b. 1939, migrated to Pakistan from Dehradun in 1947, but does not remember much about her journey. Read more

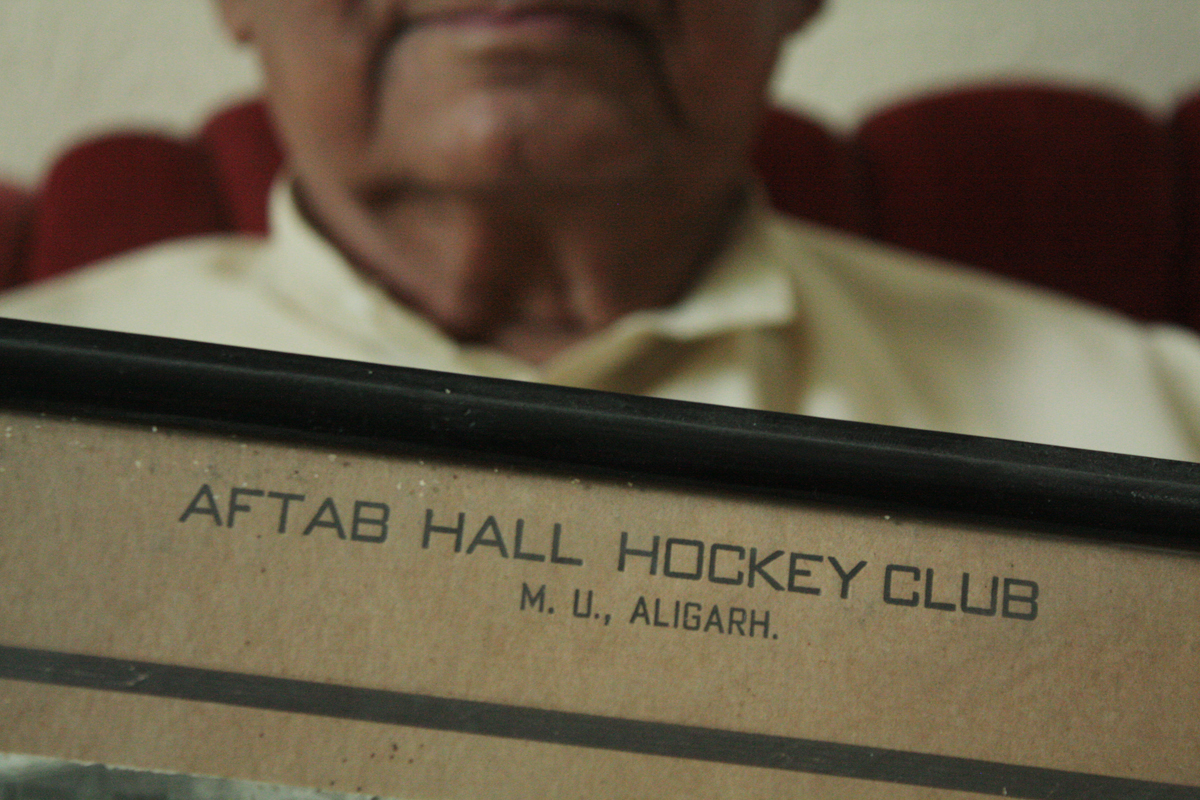

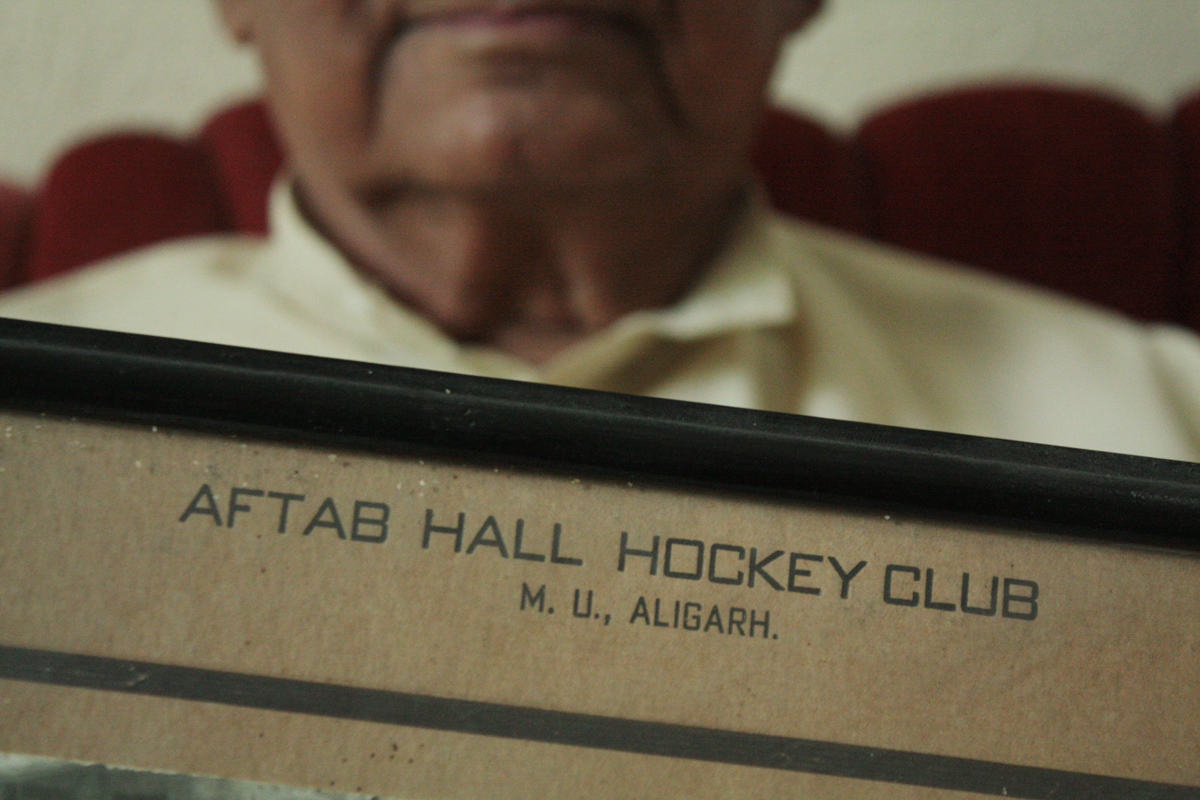

Adhami sahib spent 1947-1953 at Aligarh Muslim University. He was the only member of his family to migrate to Pakistan, taking a flight to Karachi on 23rd July, 1953. Read more

'Ab sirf yehi toh yaadgar hain. After all the years, these are my most memorable belongings.' Adhami sahib points himself out in the photograph.

"Aftab Hall Hockey Eleven 1947-48" showing the seven team members standing, their arms crossed against their chests, Nazeer Adhami first in line from the left.

The three framed photographed Adhami sahib carried with him from the Aftab Hall Hockey Club of the team him and his friends played on. Read more

THIS BIRD OF GOLD, MY LAND : THE HOPEFUL HEART OF NAZMUDDIN KHAN

Nazmuddin Khan, b. 1929 in Hauz Rani, Delhi. His father worked at Viceroy House and was offered a high-ranking position as a security official in Mohammad Ali Jinnah's guard in newly independent Pakistan. He instead chose to remain in India, and inculcated a sense of secularism in his children. more

Mr. Khan's family rebuilt their lives in Hauz Rani, where they continue to live today. In 1984, he visited his extended family in Pakistan, and though he noted that people were not so different, his home would always be Delhi. He continues to hold on to the secularism that his father has bequathed to him.

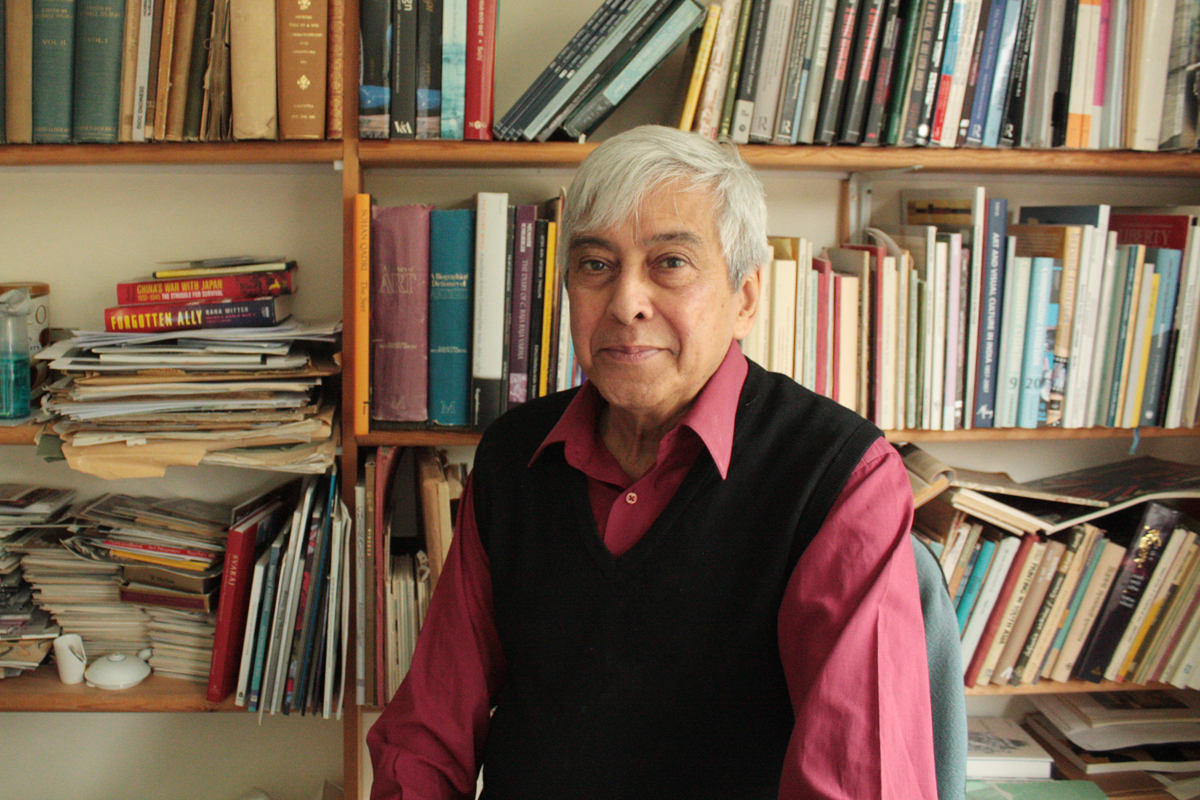

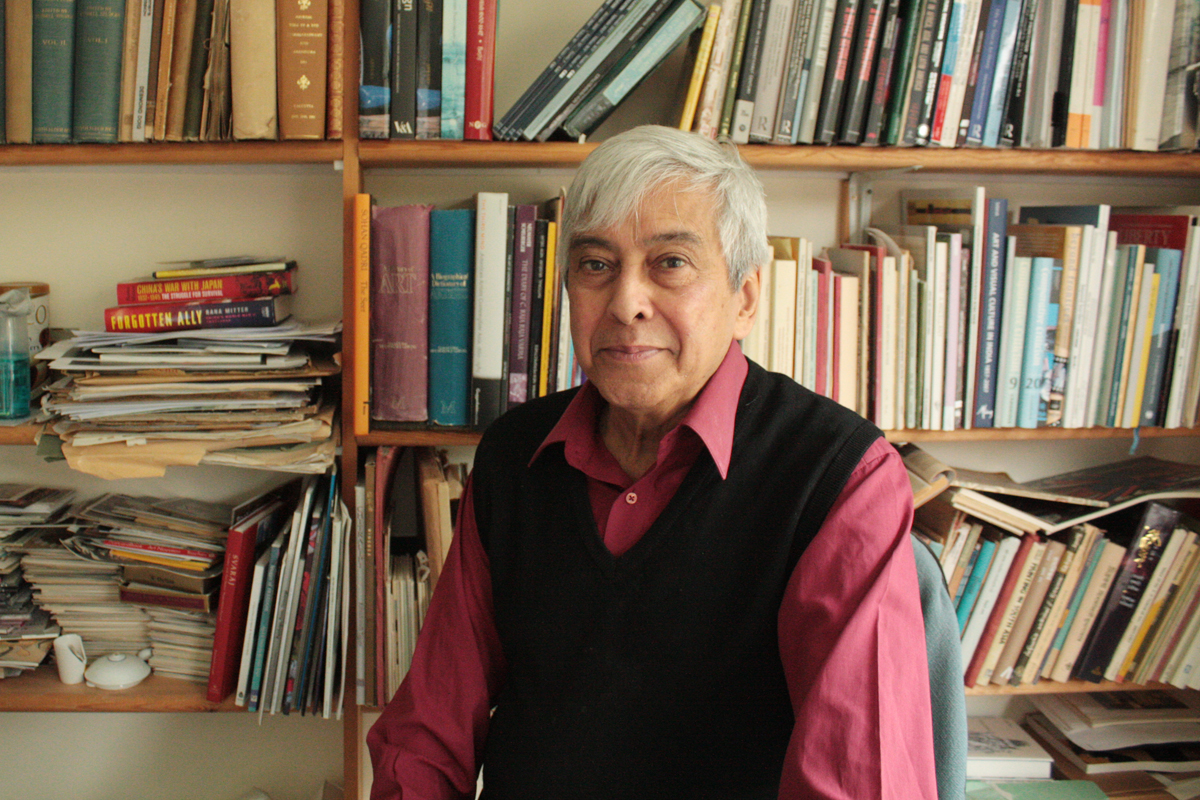

THE BOOK OF EVERLASTING THINGS : THE COLLECTION OF PROF. PARTHA MITTER

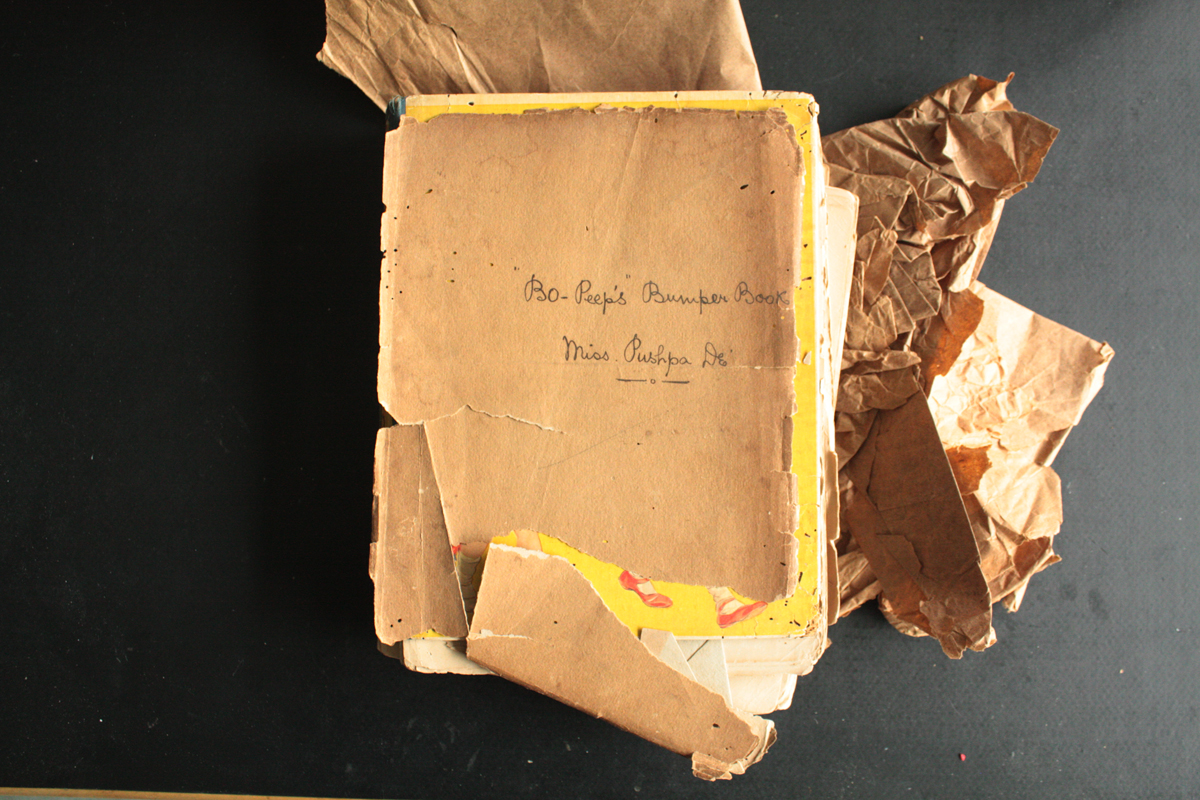

Professor Partha Mitter, born in 1938, Calcutta. The family originated from a place just outside the city called Dum Dum. Prof. Mitter witnessed the Partition of India while at sea with his family, returning from a World Tour.

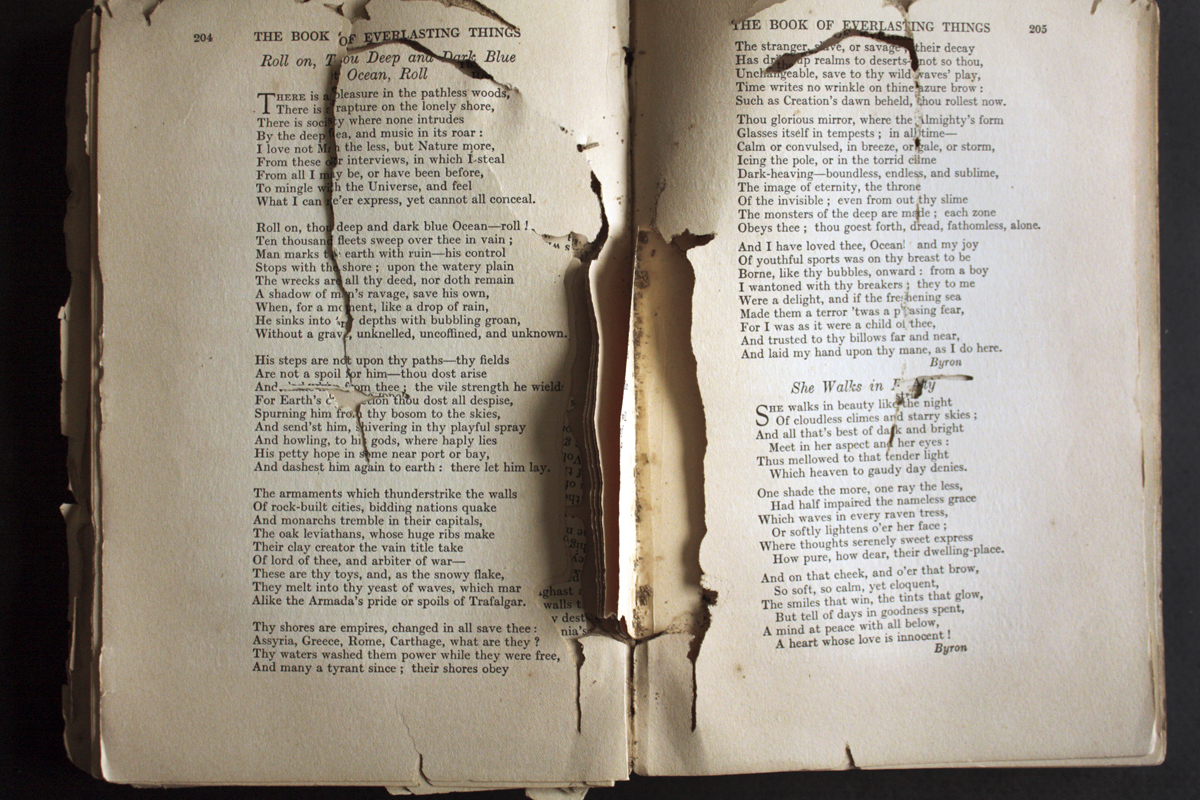

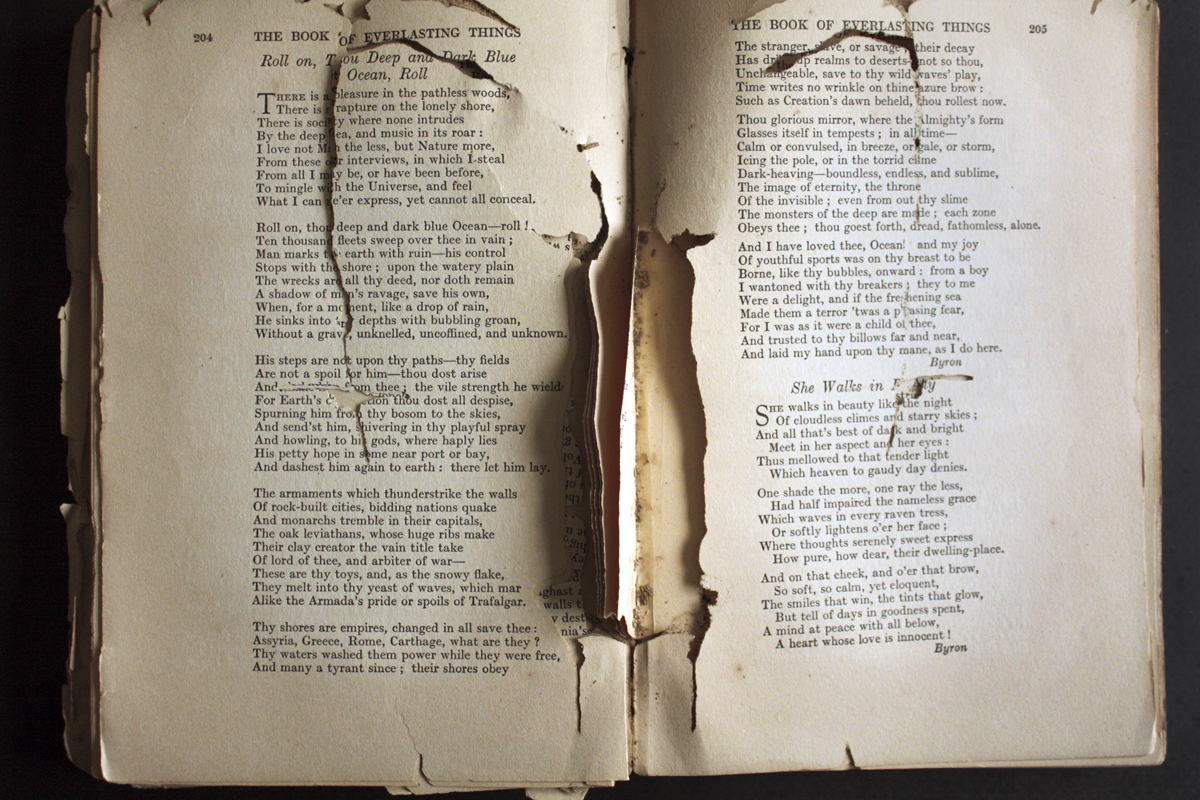

Pushpa Lata De's copy of The Book of Everlasting Things, an anthology of romantic poetry, published in 1913. During the Great Calcutta Killings of 1946, this book, along with others, was ruined during a raid in their Park Circus house.

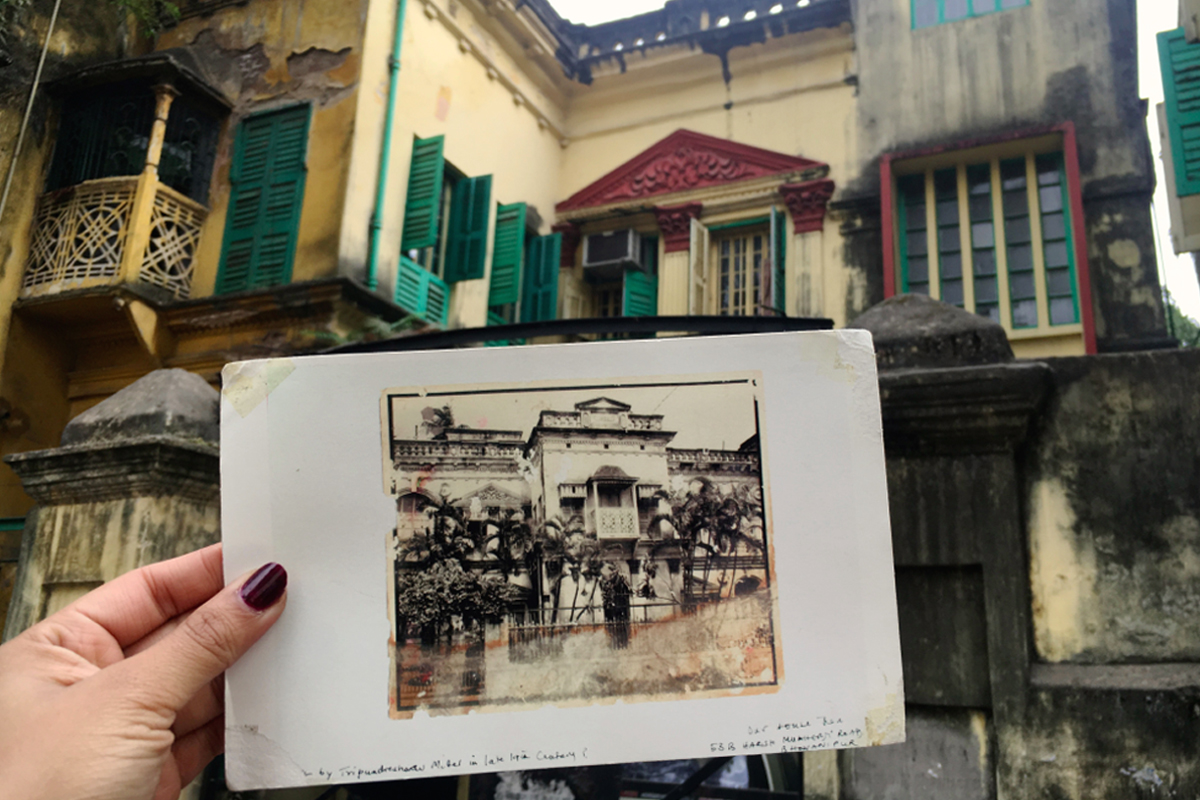

The family house on Harish Mukherjee Road, Bhowanipur, built by Tripundreshwar Mitter in late 19th Century.

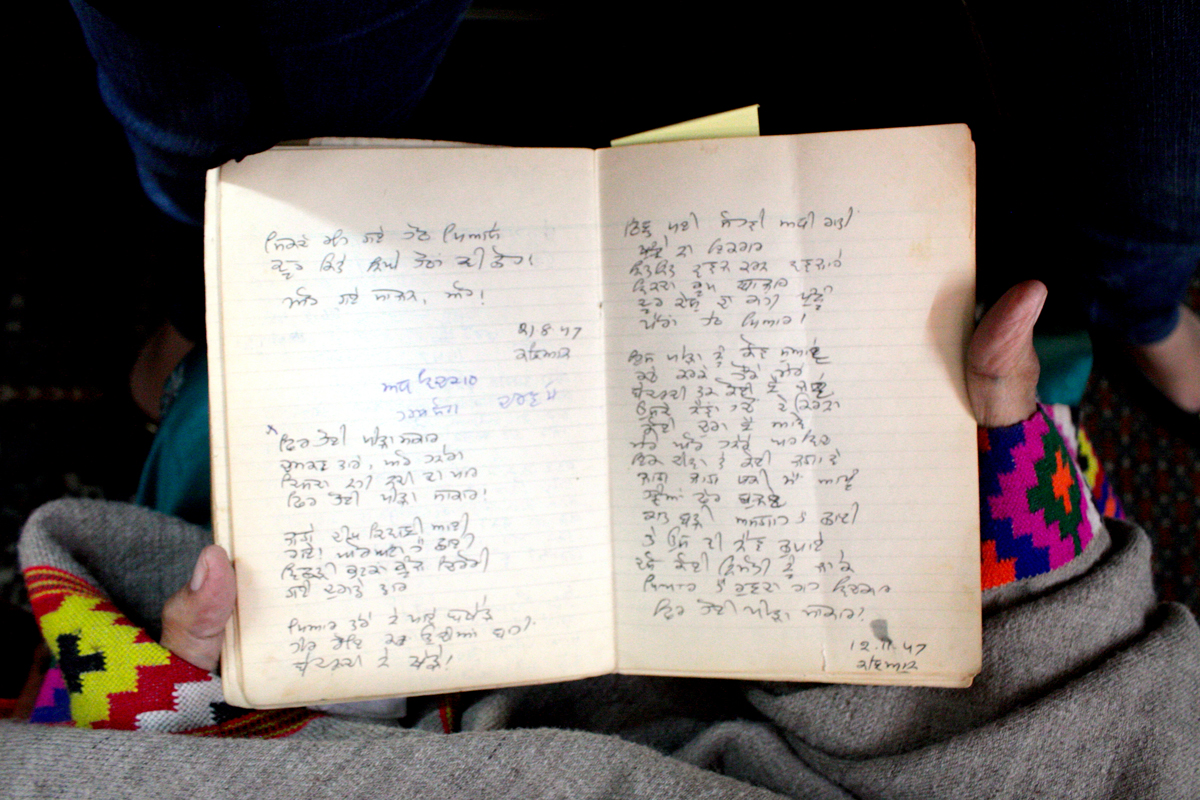

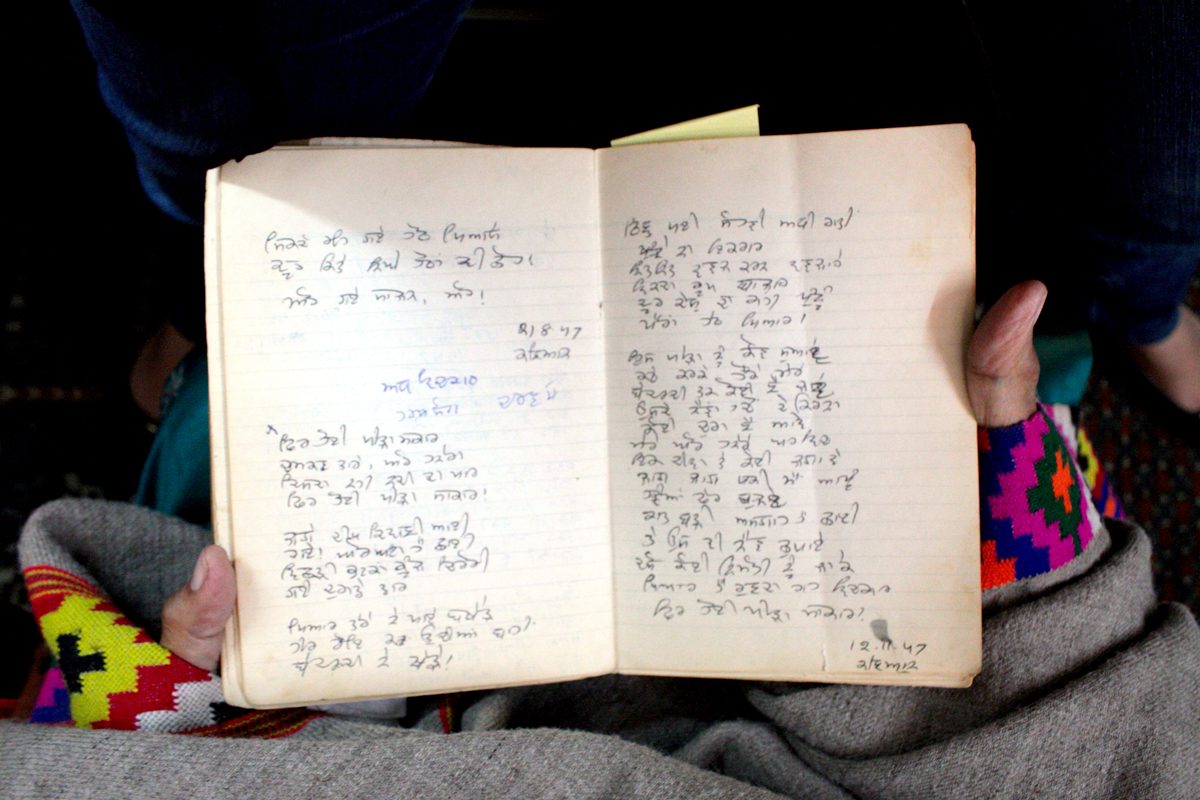

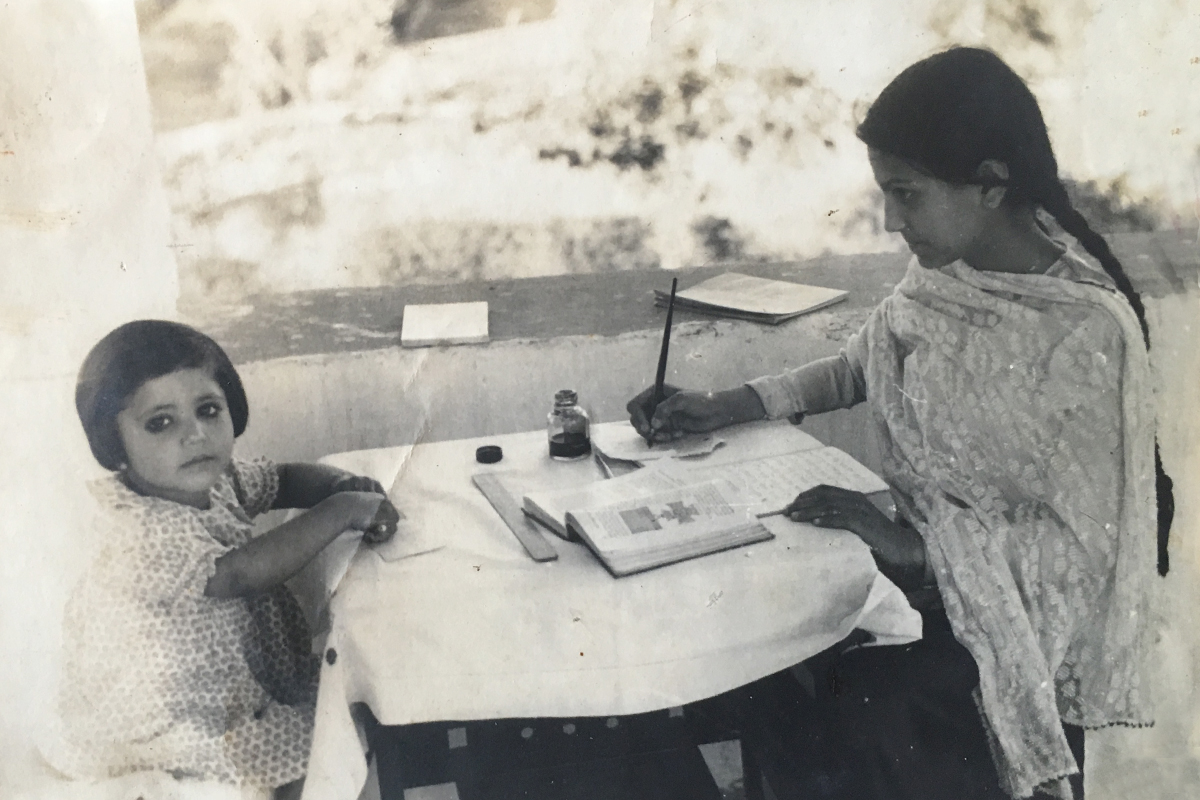

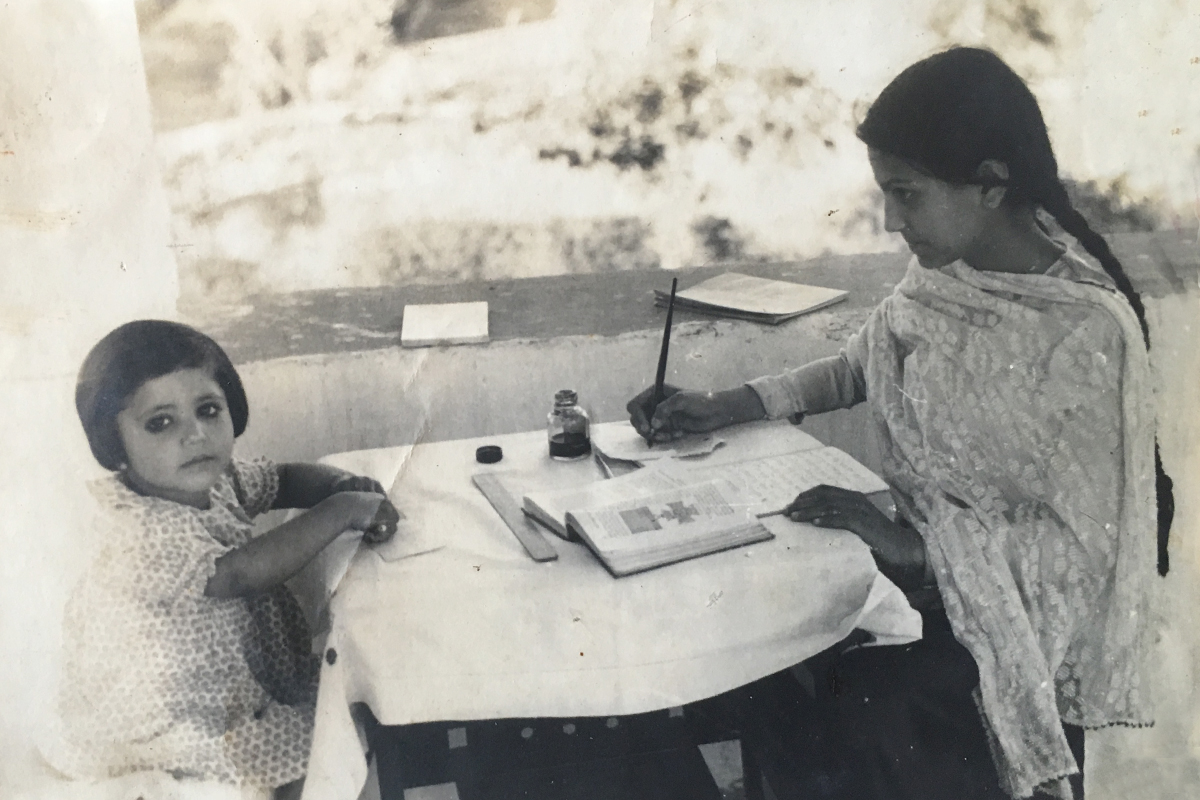

LOVE IN THE TIME OF NATIONALISM : THE POEMS OF PRABHJOT KAUR

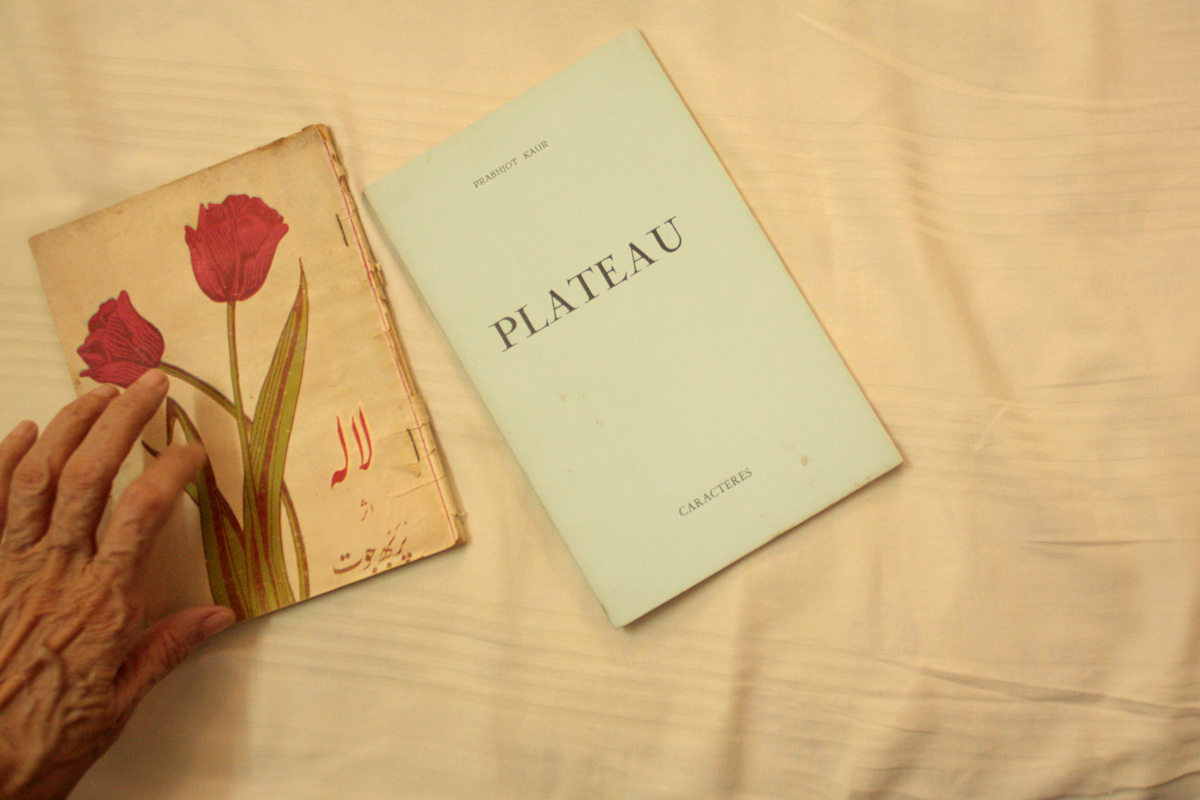

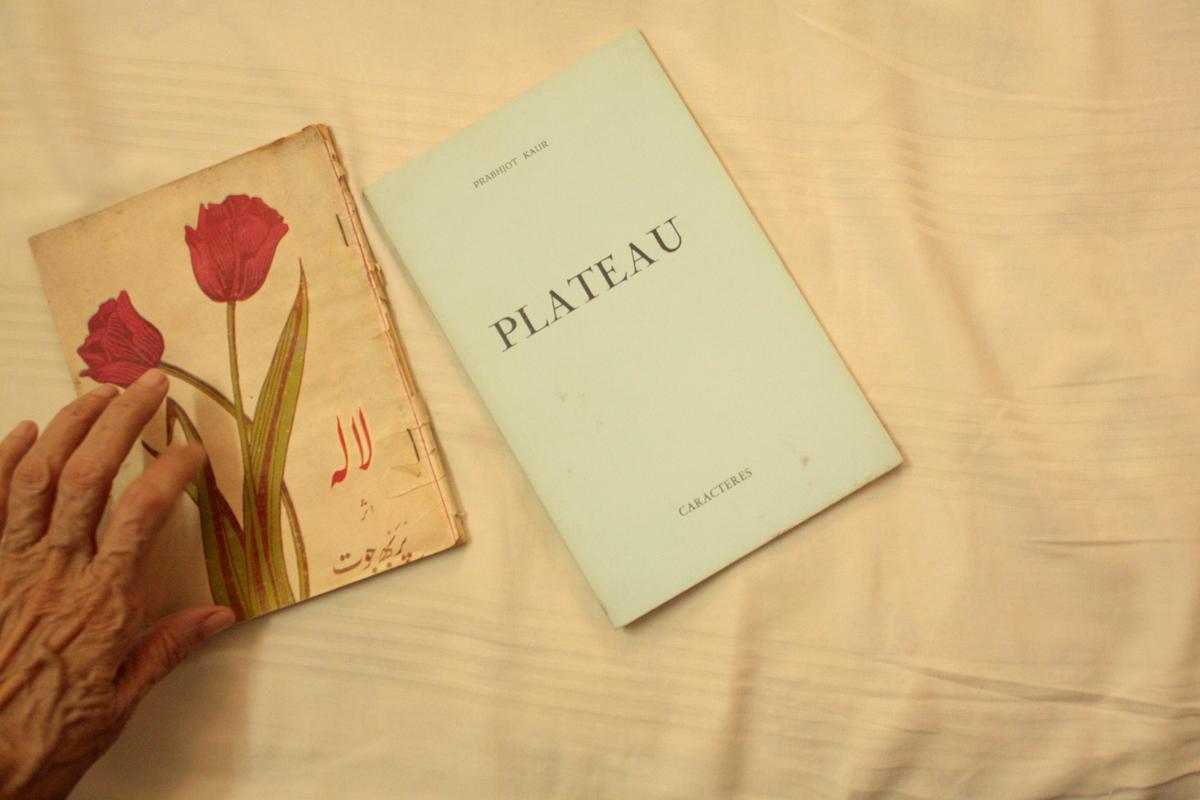

Prabhjot Kaur, born 1924 in Langrial and migrated to Kalyan. During Partition, the family was living in the Badami Bagh suburb of Lahore, and Kaur was still in college Read more

Jewellery from pre-Partition. Kaur's parents migrated beofre their children, due to a transfer in her father's work and hence, brought a significant amount of the household with them.

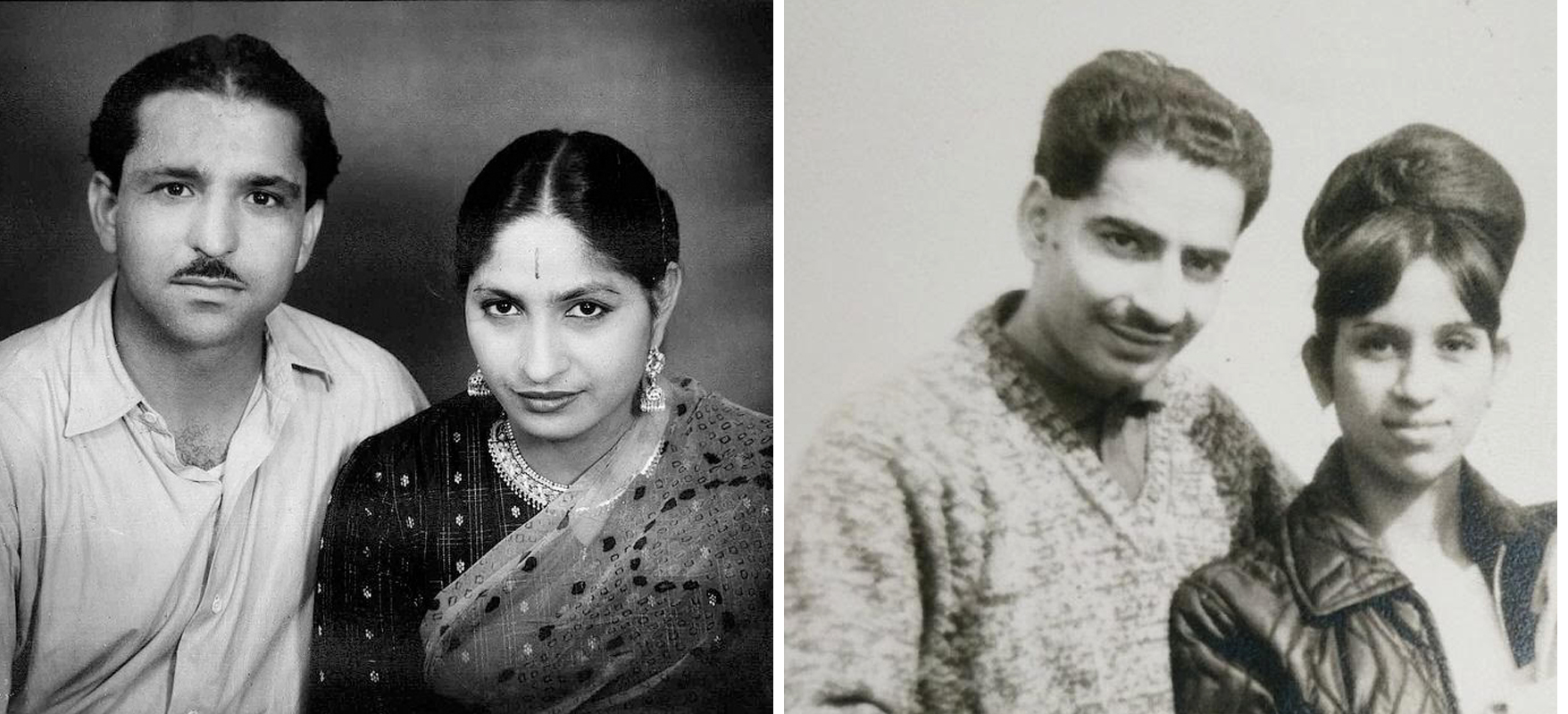

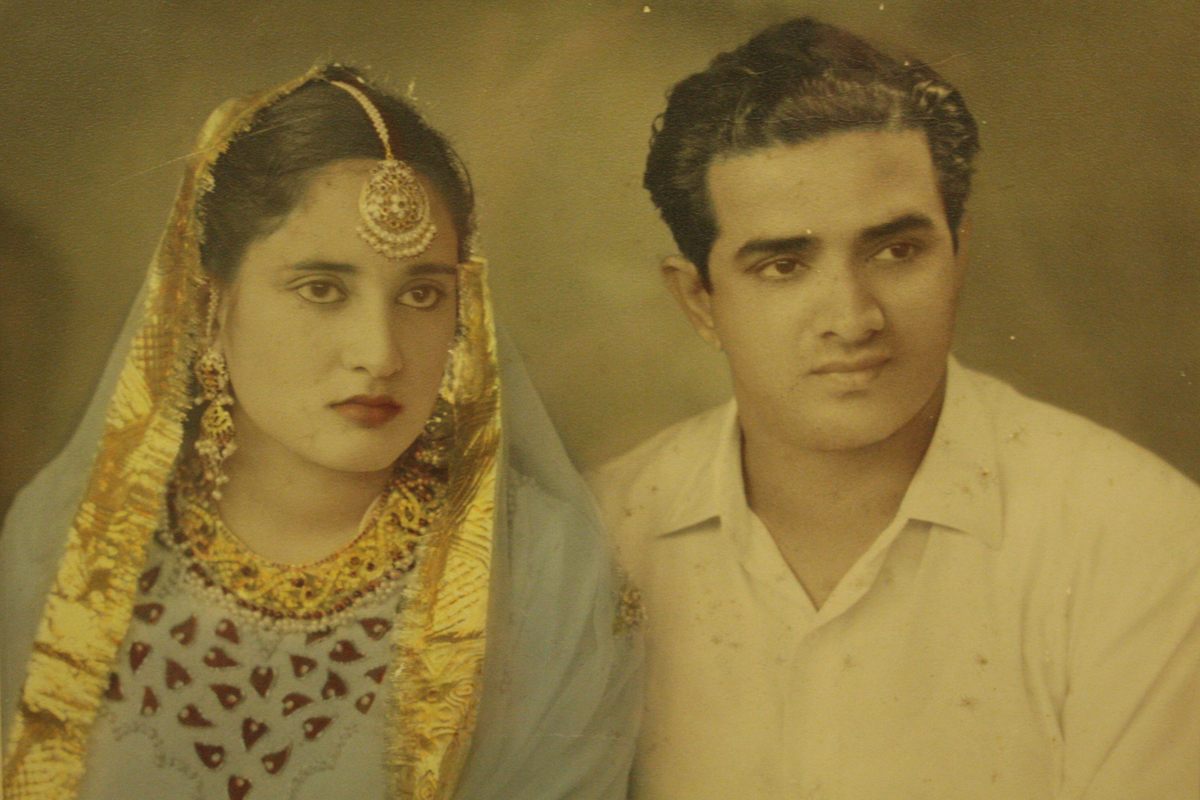

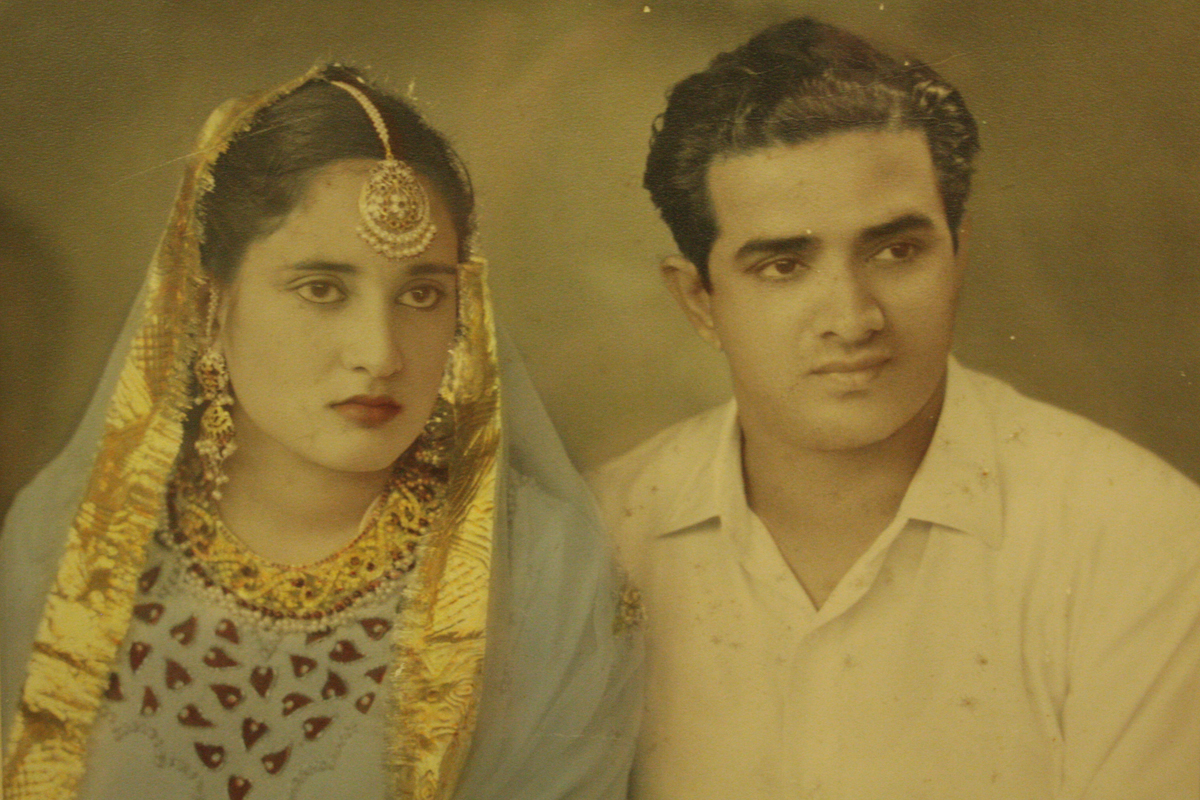

Col. Narenderpal Singh and Prabhjot Kaur married. Read more

A poem in Punjabi from the days of Partition, 1947. Read more

MEMORY OF A NATIONALIST : THE PASHMINA SHAWL OF PREET SINGH

Damage done to buildings during the earthquake in Quetta, 1935_From an album that belonged to Gunner John William Cox, Royal Artillery, India, 1934-1936, National Army Museum, London

Hindu Temple, Quetta, 1935_From an album compiled by Captain A G M Steers, Indian Army Ordnance Corps, 1932-1935, National Army Museum, London

Bruce Road, after the Quake, Quetta, 1935_From an album compiled by Captain A G M Steers, Indian Army Ordnance Corps, 1932-1935, National Army Museum, London

Preet Singh, born 1939 in Quetta and migrated to Mussourie in the summer of 1947. She was the youngest of her siblings.

THE LEXICON OF MY LAND IS DEVOID OF EMOTION : THE BATTLE-HARDENED MEMORABILIA OF LT. GEN S. N SHARMA

L-R - Lt Gen S.N Sharma, Mrs. Kumidini Sharma, Mrs. Swaroop Sharma, Brigadier (later Gen) Vishwa Nath Sharma

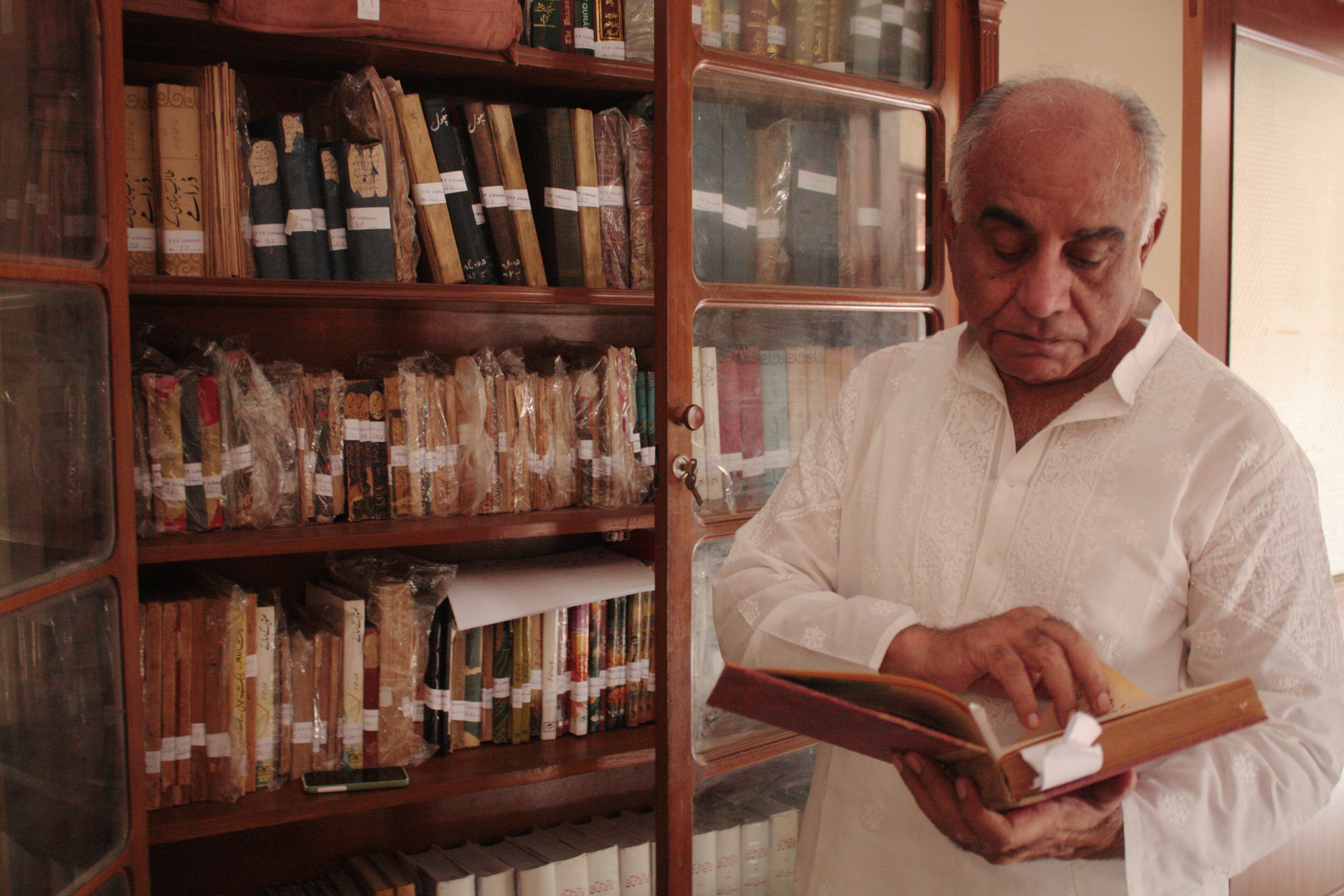

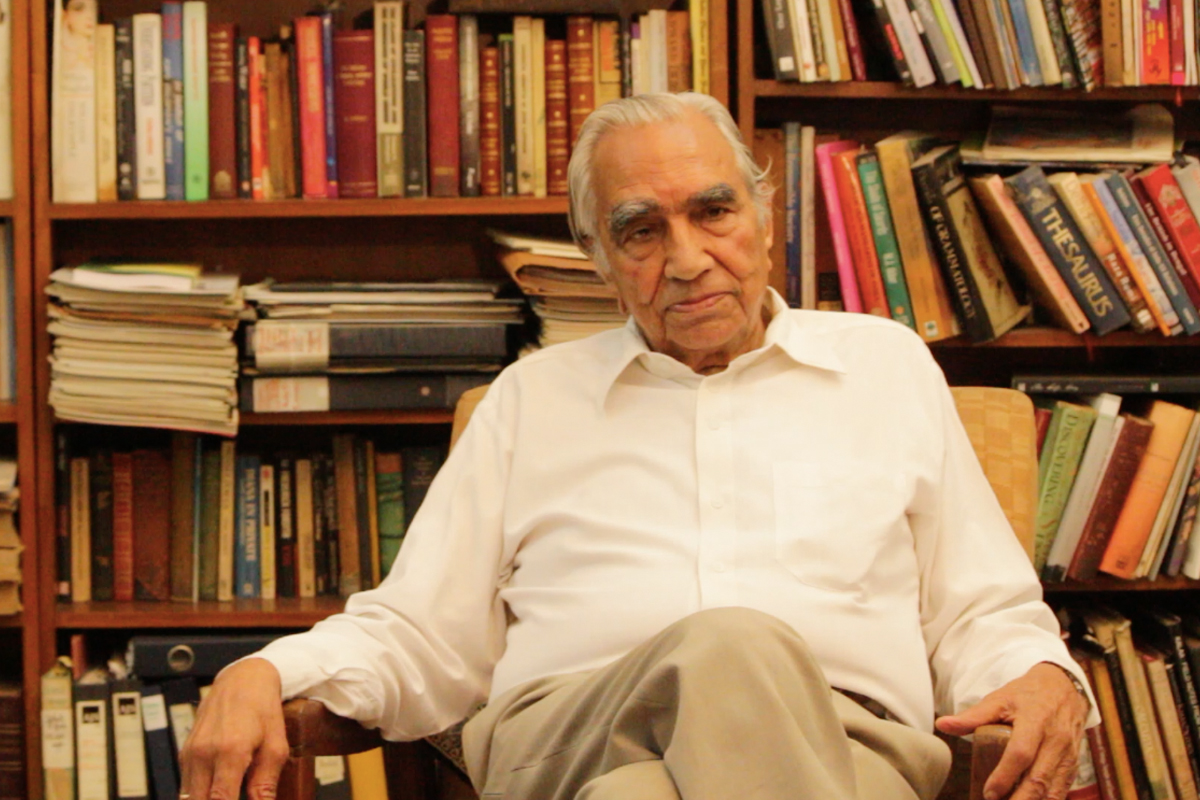

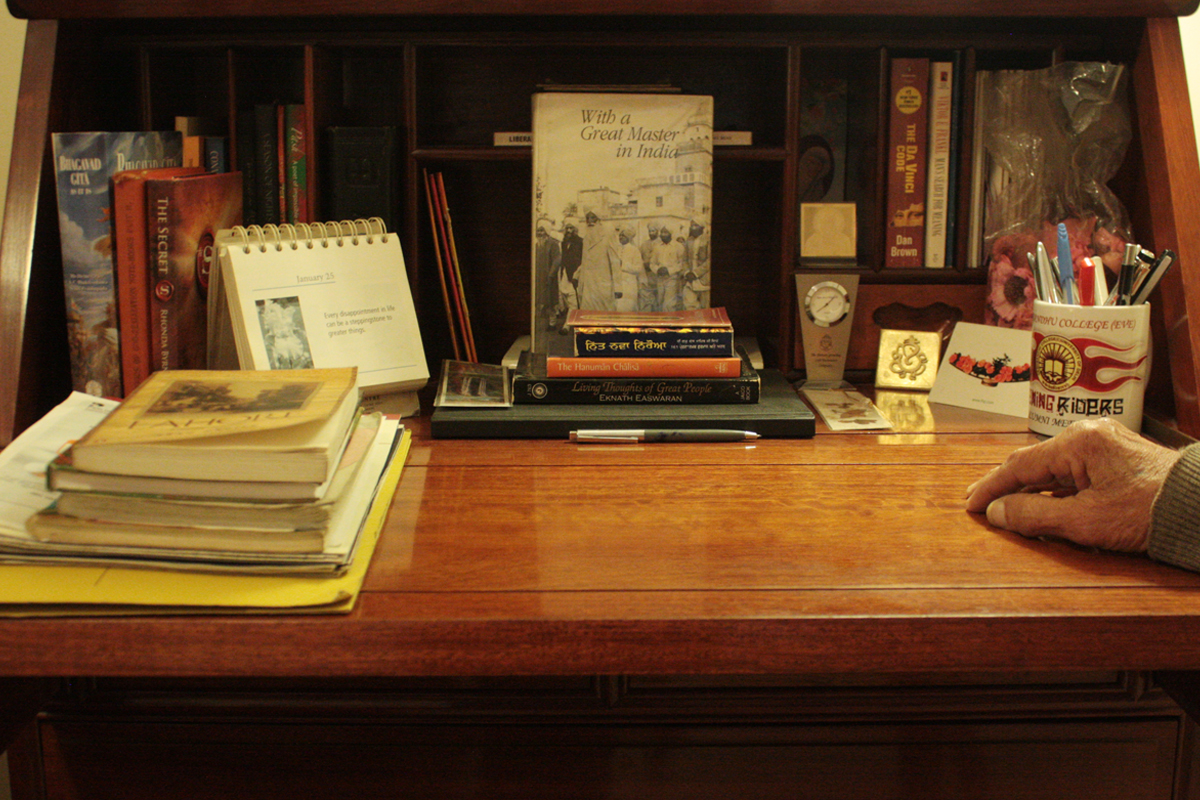

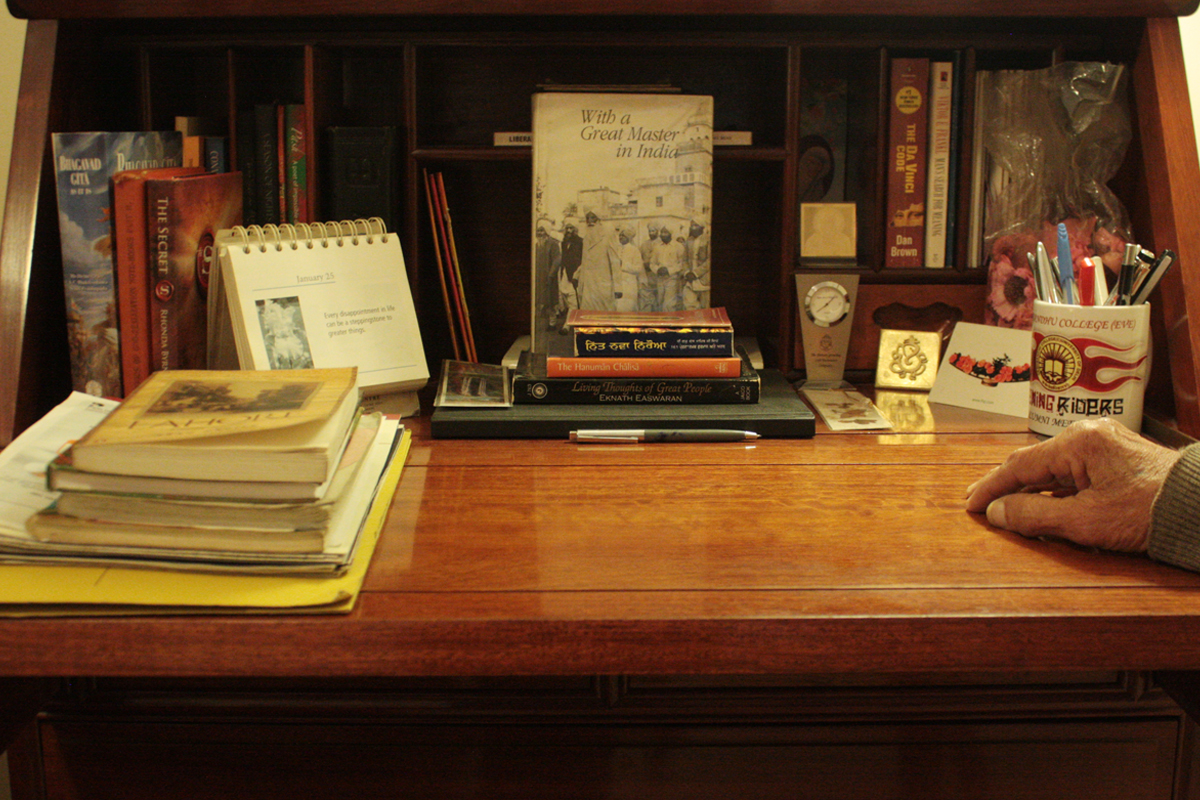

A HEART OF MORTGAGED SILVER : THE ASSORTED CURIOS OF PROF. SAT PAL KOHLI

Prof. Sat Pal Kohli, born on August 9, 1926 in Lahore and migrated to Amritsar. That the date of his birthday coincided with the date of the Quit India Movement in 1942, was a matter of great pride for him. Read more

Prof. Kohli, who for many years of his life, taught English literature at the Delhi College of Art, was an ardent reader of anything written on the city of his birth. This is his worktable in Delhi, a snapshot of his days.

Their house in Garhi Shahu was full of valuables that people had mortaged with Shiv Devi. Before the family migrated, she went around the house, collecting valuable items - like this silver glass - to either sell or use in building a new life.

A silver cigarette case from World War I, two-and-a-half inches by three-and-a-half inches, and in excellent condition, which had been mortaged by a neighbour.

STATELESS HEIRLOOMS : THE HAMAM-DASTA OF SAVITRI MIRCHANDANI

Savitri Mirchandani (née Gidwani), b. 1922 in Hyderabad, Sindh, and migrated to Bombay by ship in November 1947. Her husband, an officer in Sindh Police, joined her in 1948.

Maya Mirchandani took her grandmother to Sindh in 2006. Years had passed, Savitri couldn't recognize Karachi anymore. But in Hyderbad, she found the house she was born in.

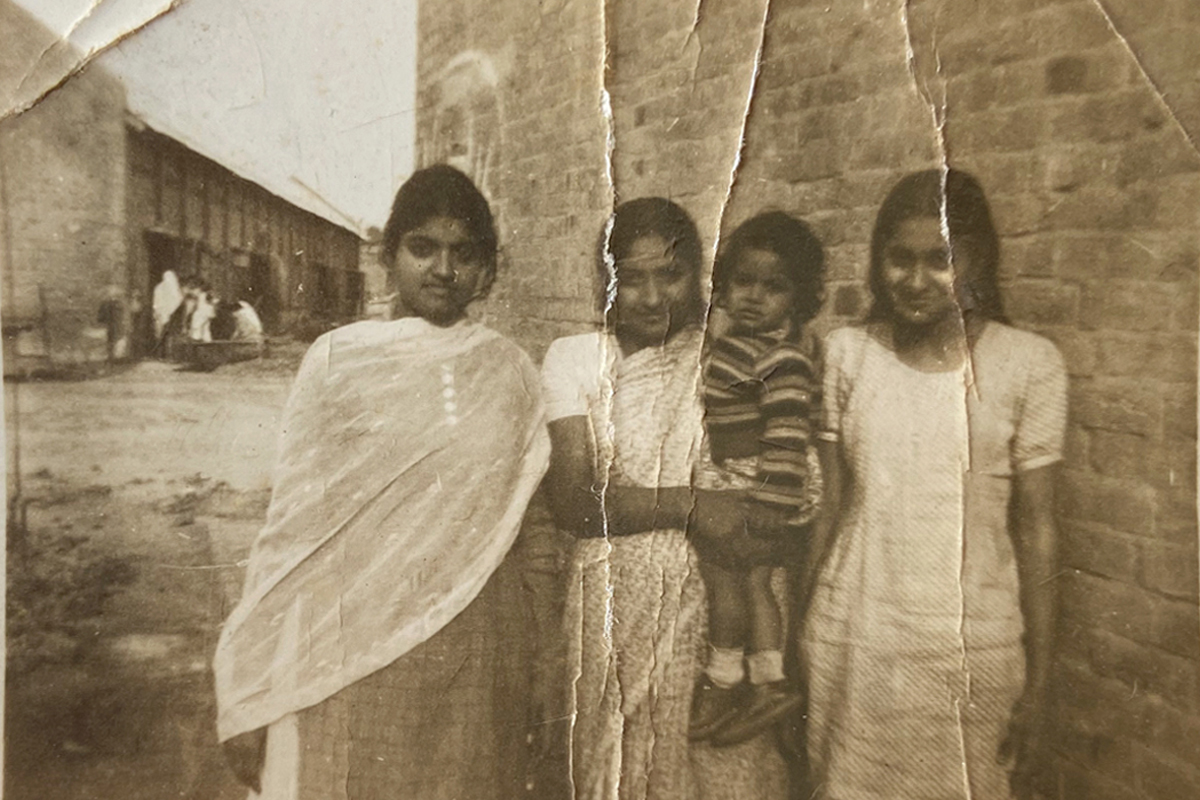

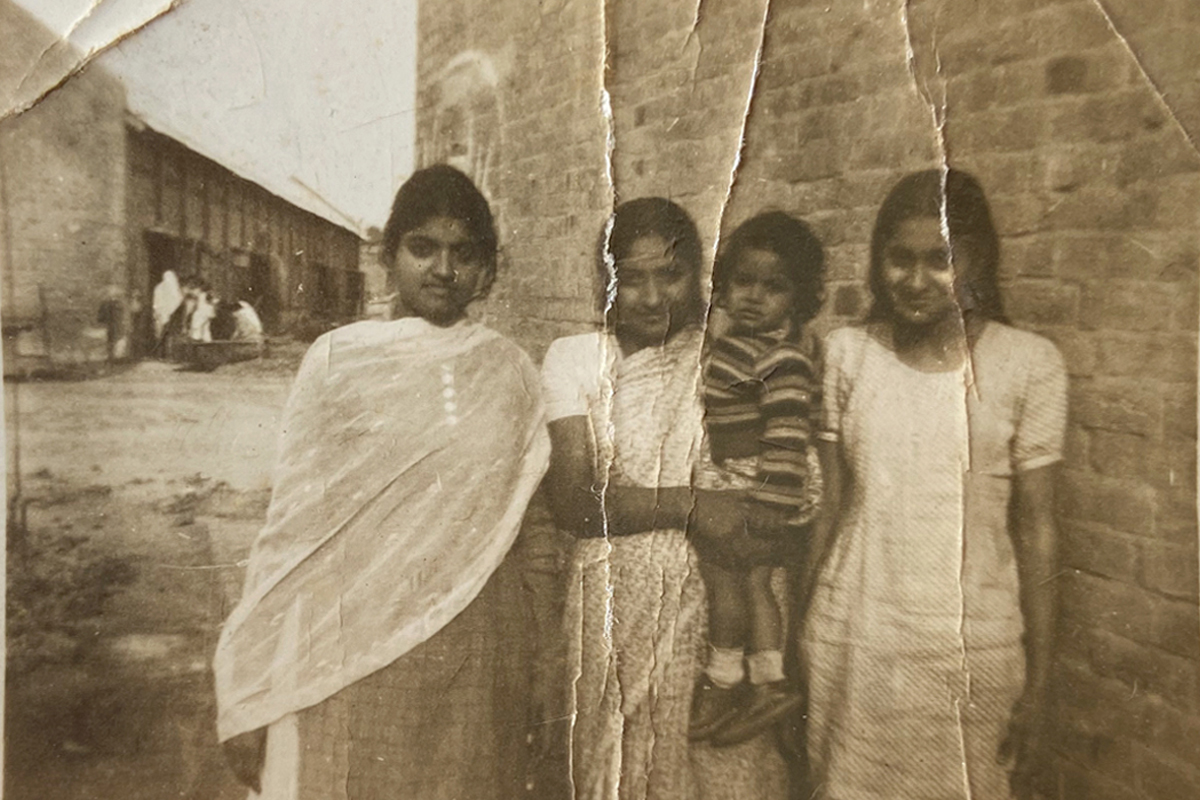

The Mirchandani women in Delhi. Shobha Sengupta (L), Savitri's eldest daughter, was also born in Karachi in 1946, and was one year old at the time of Partition. Read more

The brass hamam-dasta, mortar & pestle, that quietly that made its way to indepedent India, packed in Savitri's belongings as she made the three day voyage from Karachi to Bombay.

Savitri's benarasi wedding sari that her husband, Sunder Mirchandani, carried with him from Sindh, when he was finally able to travel to India six months after his family.

FROM THE FOLDS OF LIFE : THE HOUSEHOLD ITEMS OF SITARA FAIYAZ ALI

Sitara Faiyaz Ali, born in 1924 in Lyallpur (present day Faisalabad), and migrated to Mianwali, via Dalhousie, Tarn Taran, Bharowal, Amritsar and Lahore. Read more

With her daughter, Shahnaz Akhtar, who was a year and a half old at the time of Partition. The family had traveled from their home in Gurgaon to their summer house in Dalhousie, when Partition was announced.

THE BEDI FAMILY

The ancestor, Sir Baba Khem Singh Bedi of Kallar (1830-1905), photographed at Lafayette Studio, England, 1902. Image from a catalog in the family's possession. Read more

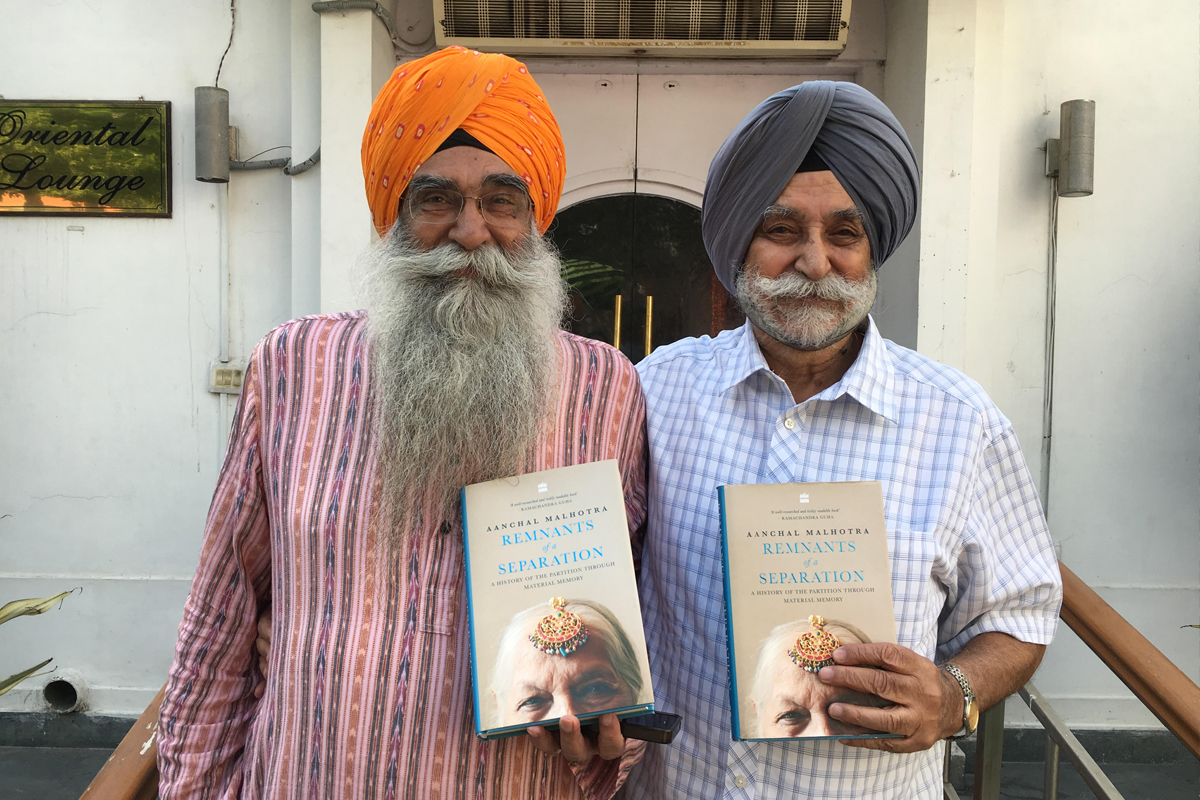

Brothers, Mr. Gurdip Singh Bedi (left) and Col. Harinder Singh Bedi (right) in Delhi, 2017. They now live in Kehkashan Cottage, Dalhousie, which was bought by their father, Baba Surinder Singh Bedi after Partition.

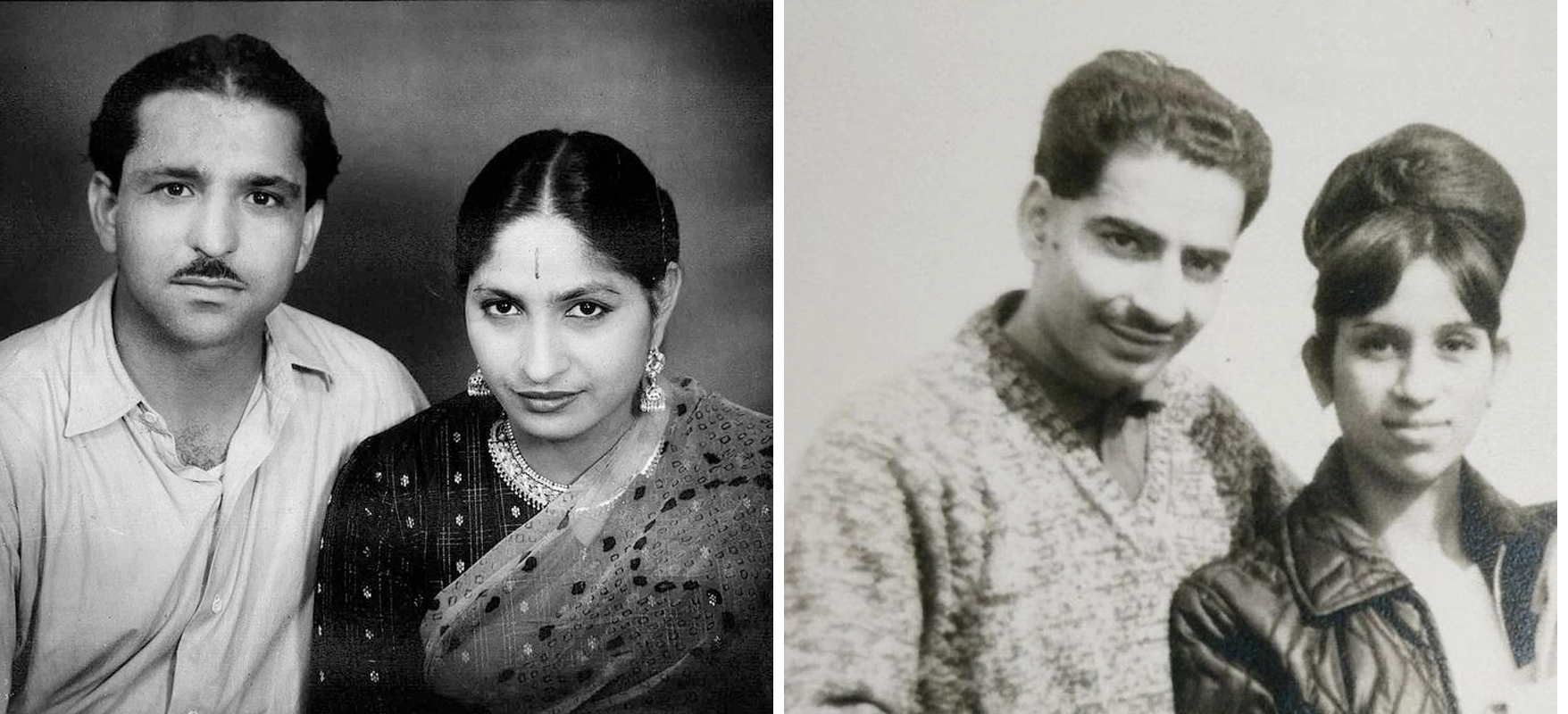

The Bedi brothers in their youth. The family migrated from Rawalpindi on March 6, 1947 and went to Kasauli, where they had already relatives. Read more

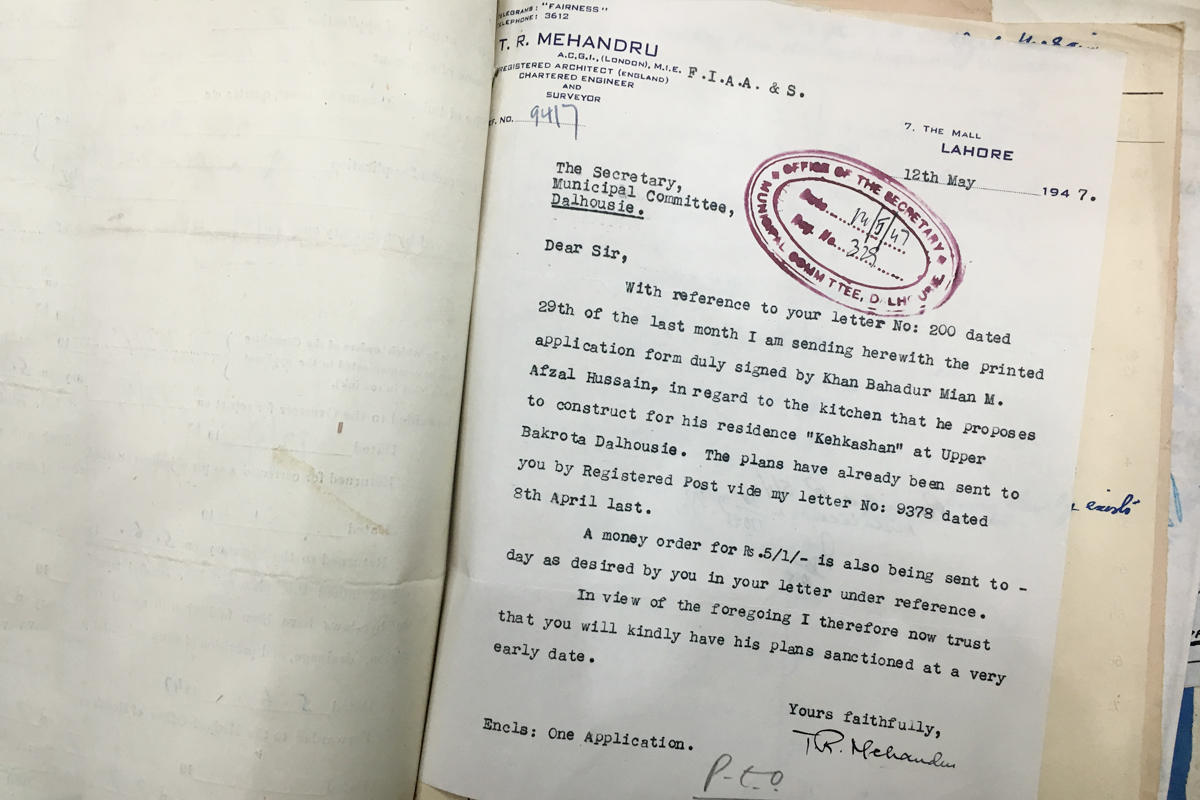

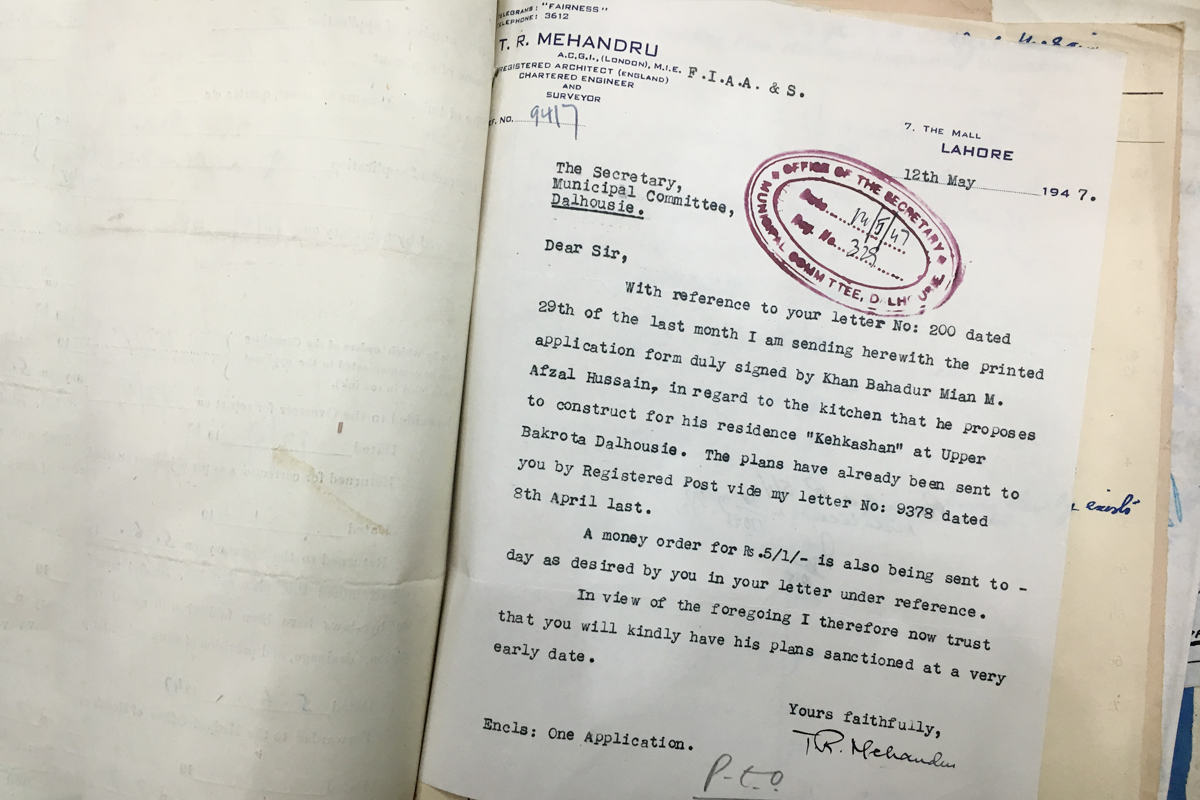

THE STORY OF KEHKASHAN COTTAGE, DALHOUSIE

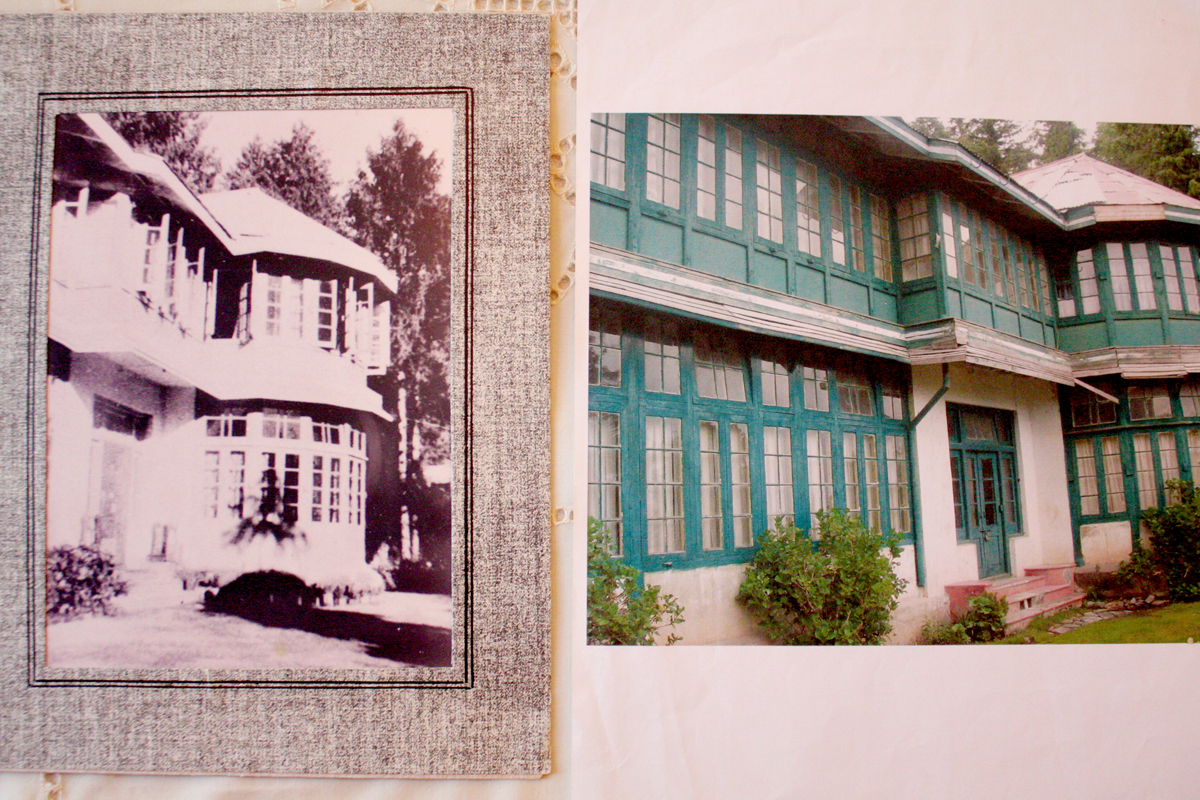

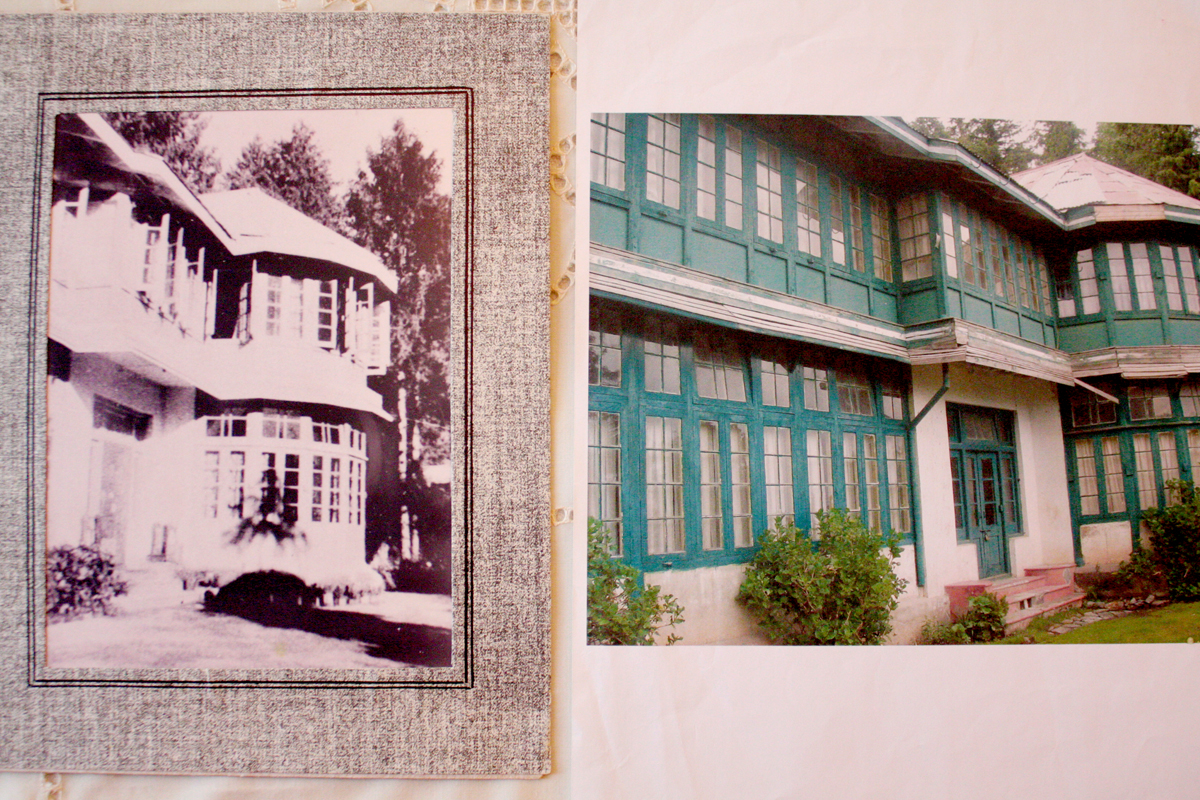

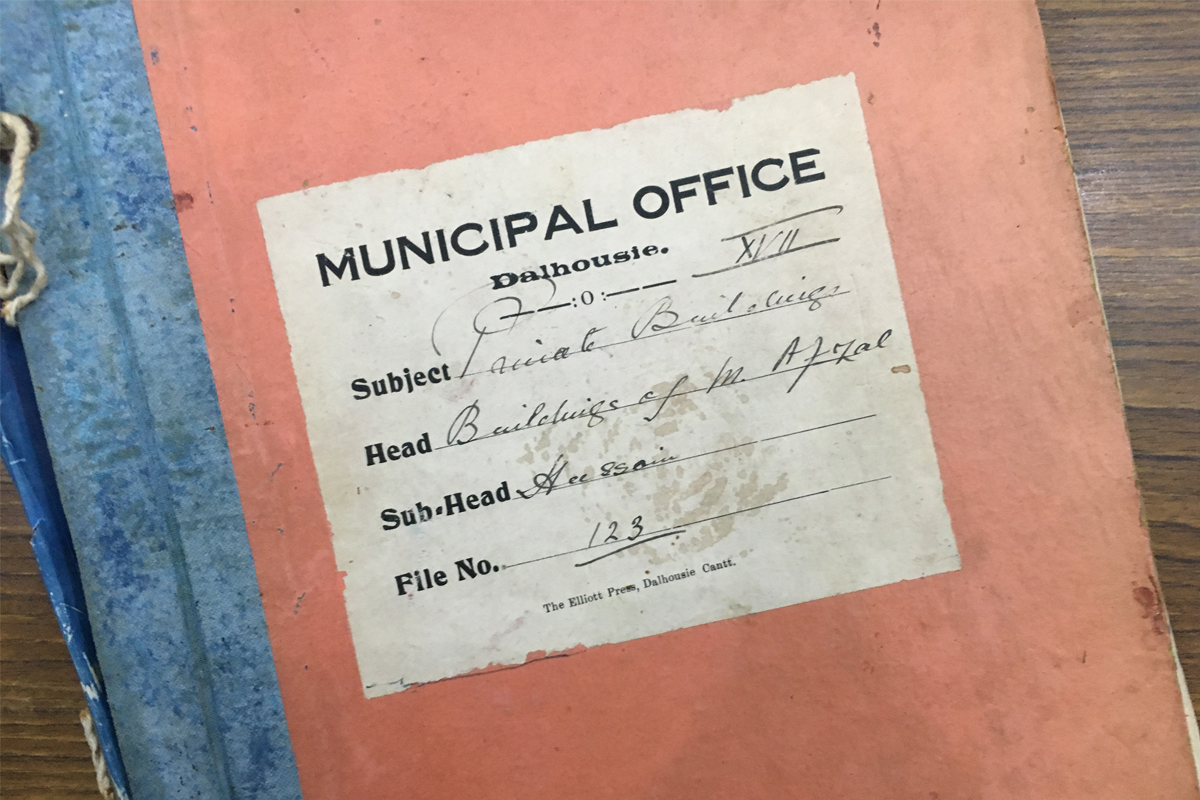

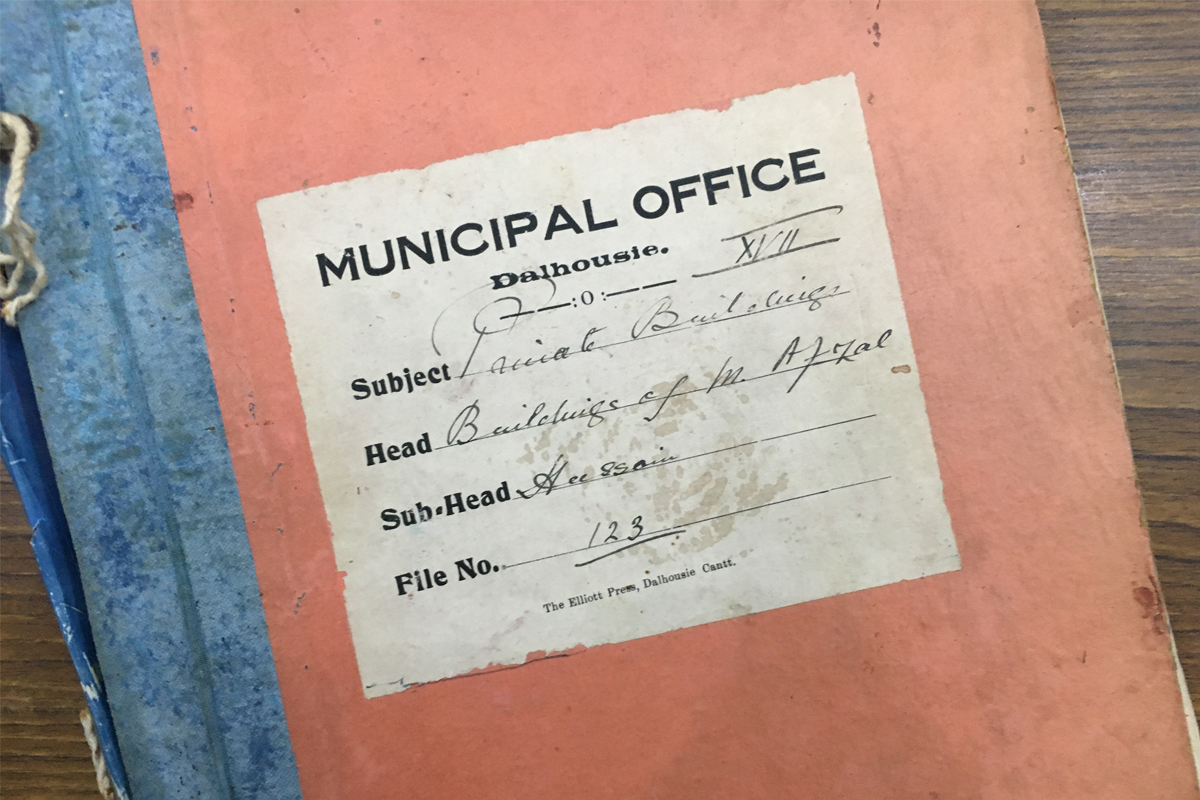

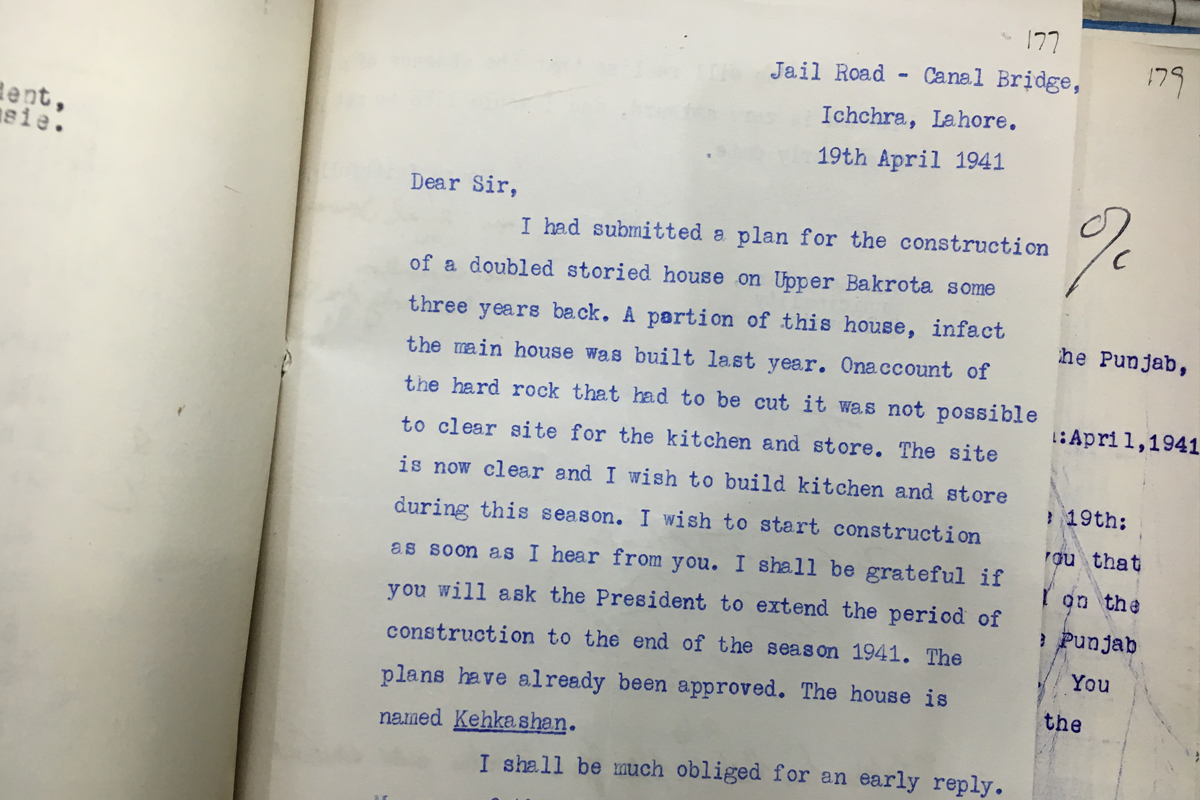

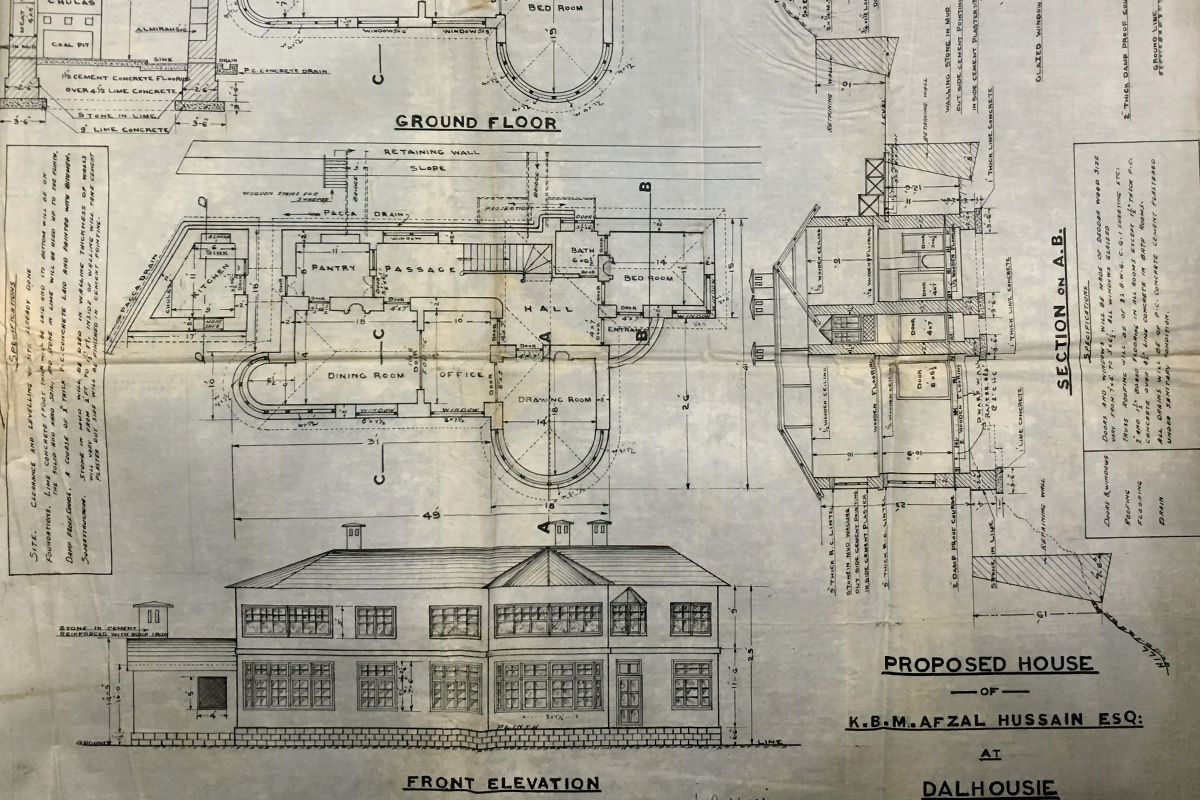

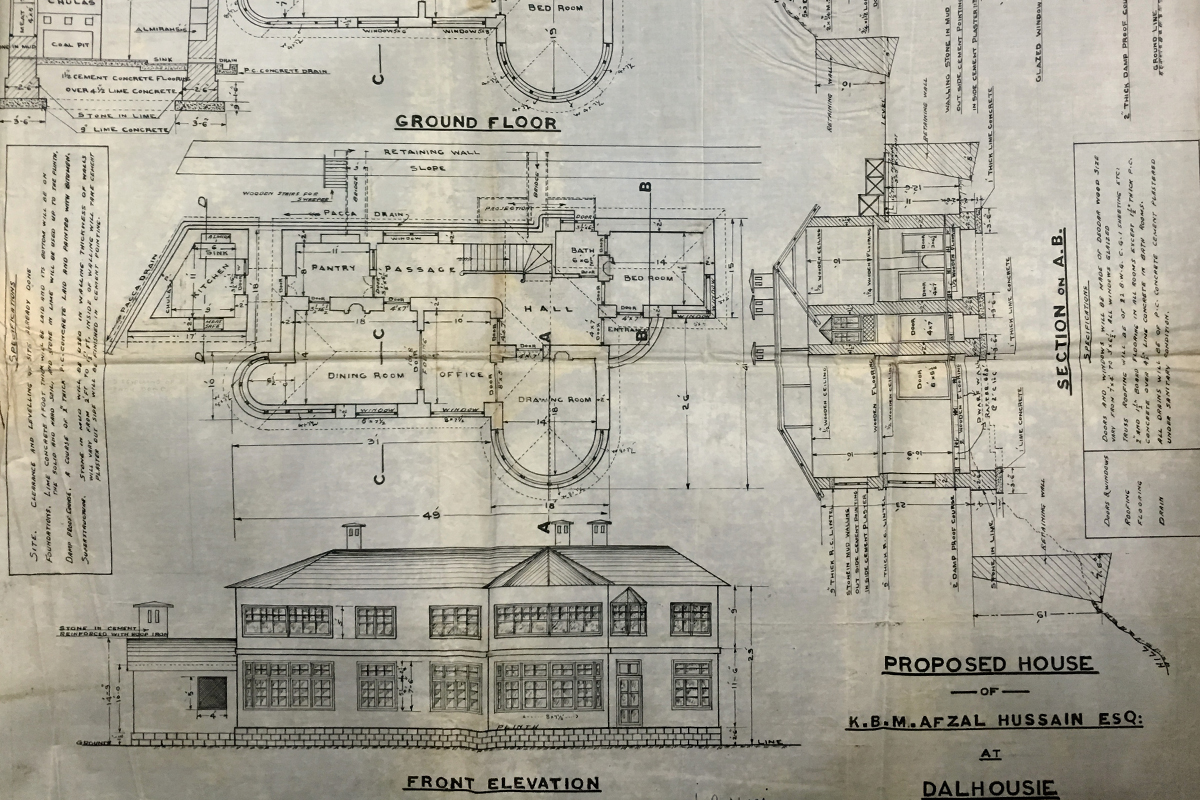

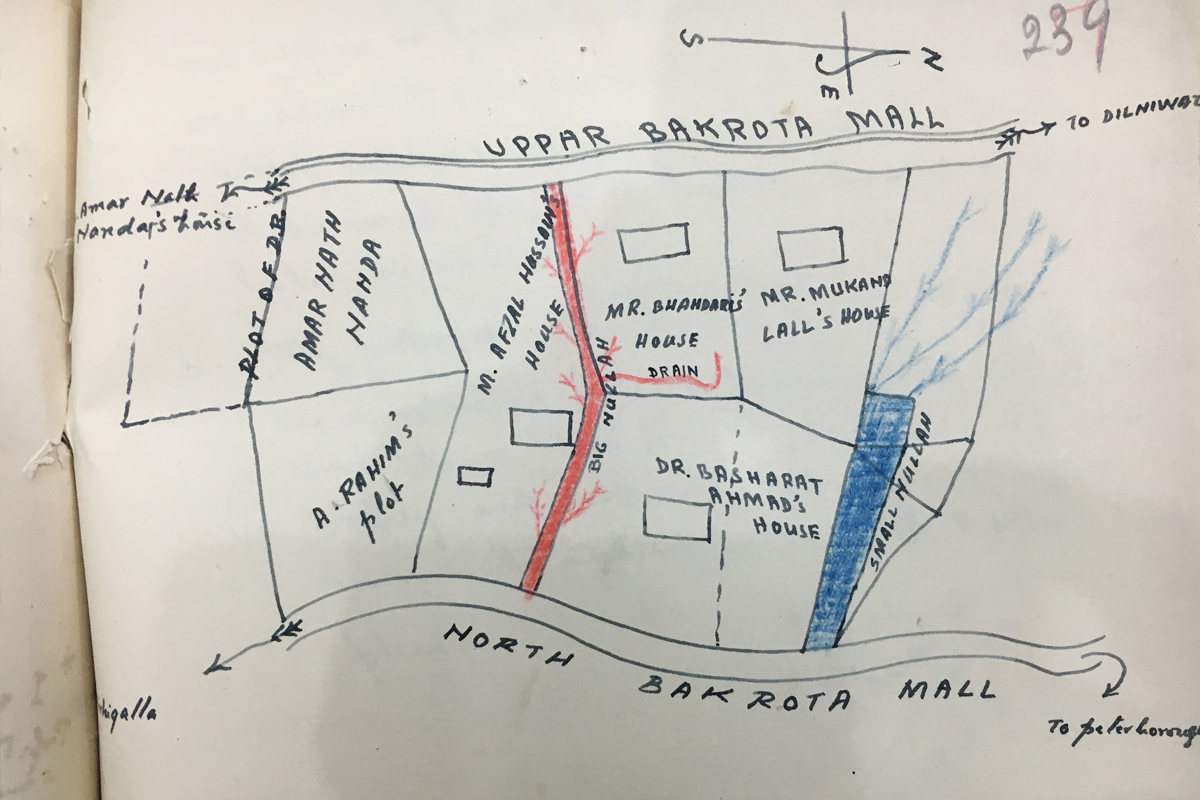

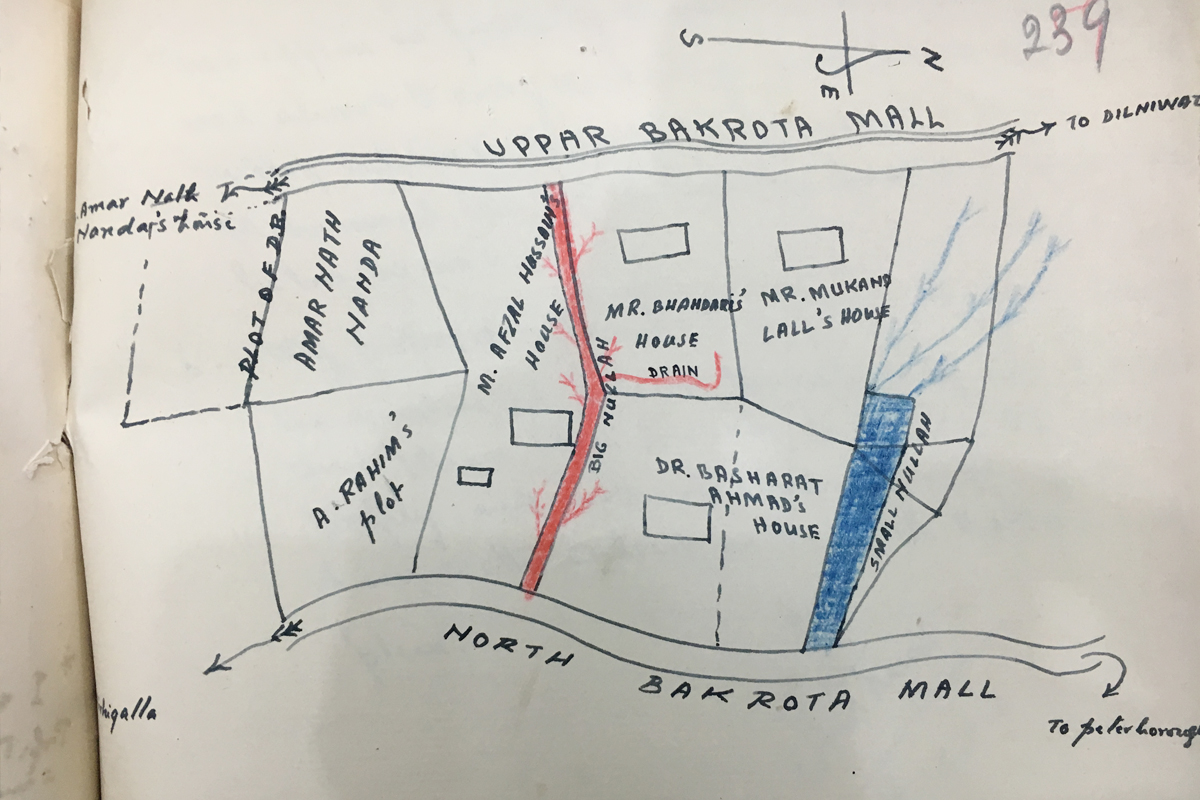

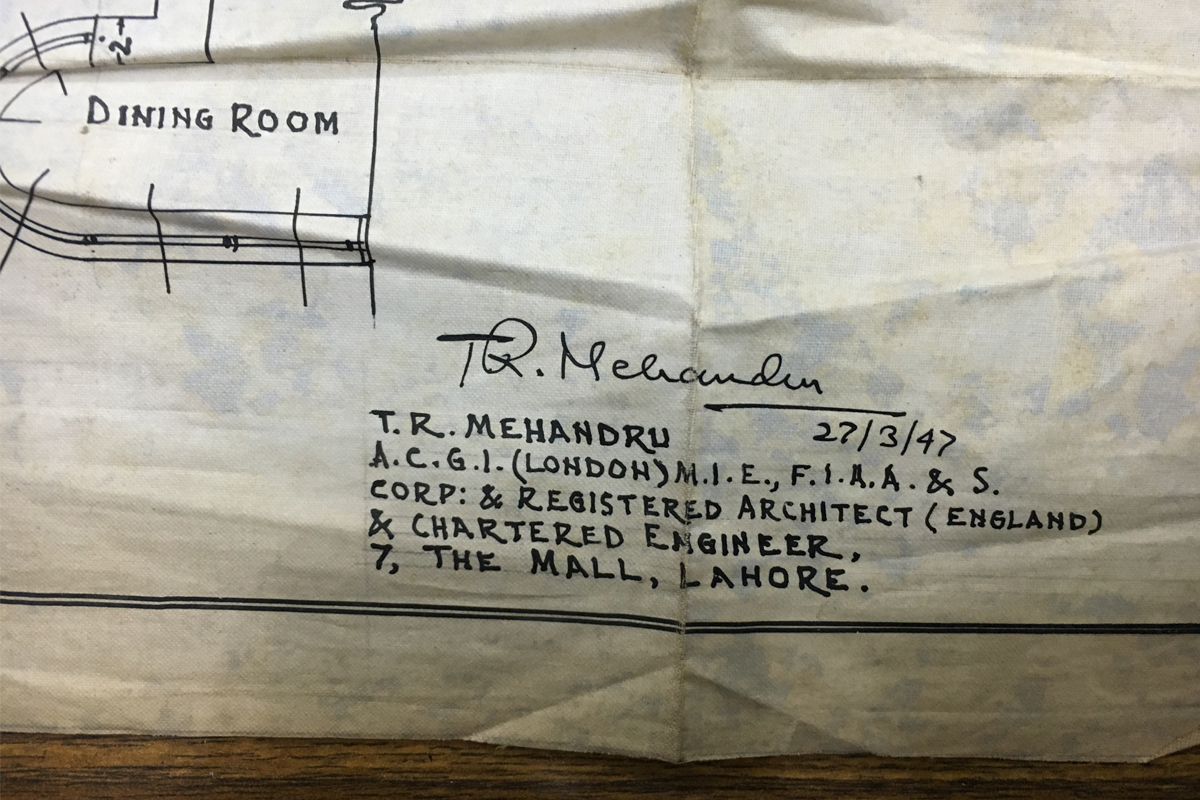

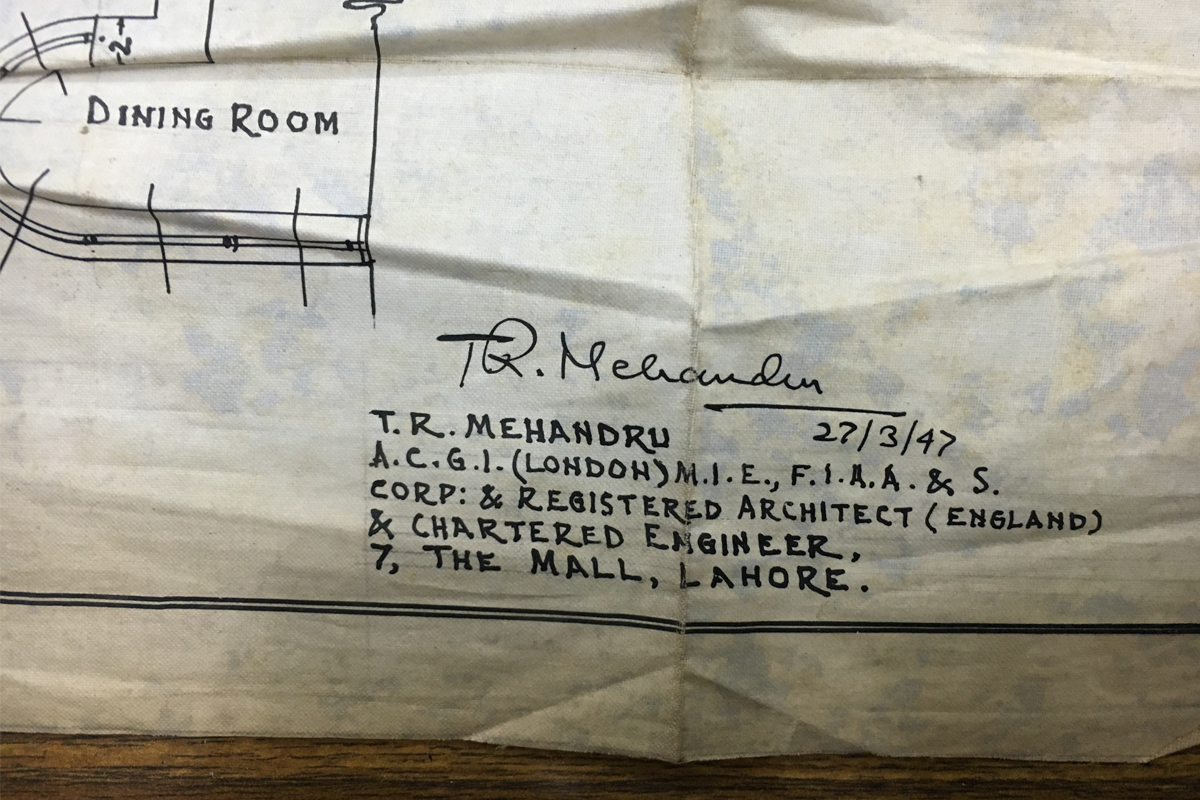

Khan Bahadur Muhammad Afzal Husain purchased land in Dalhousie in 1932 for the construction of a summer house, and by 1943, the cottage with green shutters – Kehkashan, meaning a galaxy – was standing on the eastern aspect of the Upper Bakrota Hill. The house, accented by stars carved into the ceilings, or a round sun-room, was inspired by Husain's daughters - Sitara (star) and Surya (sun). In the summer of 1947, Husain's entire family was holidaying in Dalhousie, when Partition is declared. Gurdaspur District (of which Dalhousie was a part) fell in India, and the family was made to flee overnight. Mian Afzal Husain was the last to leave, unable to believe that his country could be divided, unable to so abruptly leave his beloved Kehkashan behind. The house was abandoned, until 1953, when it was bought by Baba Surinder Singh Bedi, along with other properties on the hill. In the autumn of 2017, after the publication of Remnants, I traveled to Dalhousie to see the house whose history is shared by two families on either side of the border. Read the full piece here.

Kehkashan cottage, Dalhousie, occupied pre-Partition by the Husain family and post-Partition by the Bedi family.

The formal living room on the ground floor. The original structure of the room as well the furniture has been retained.

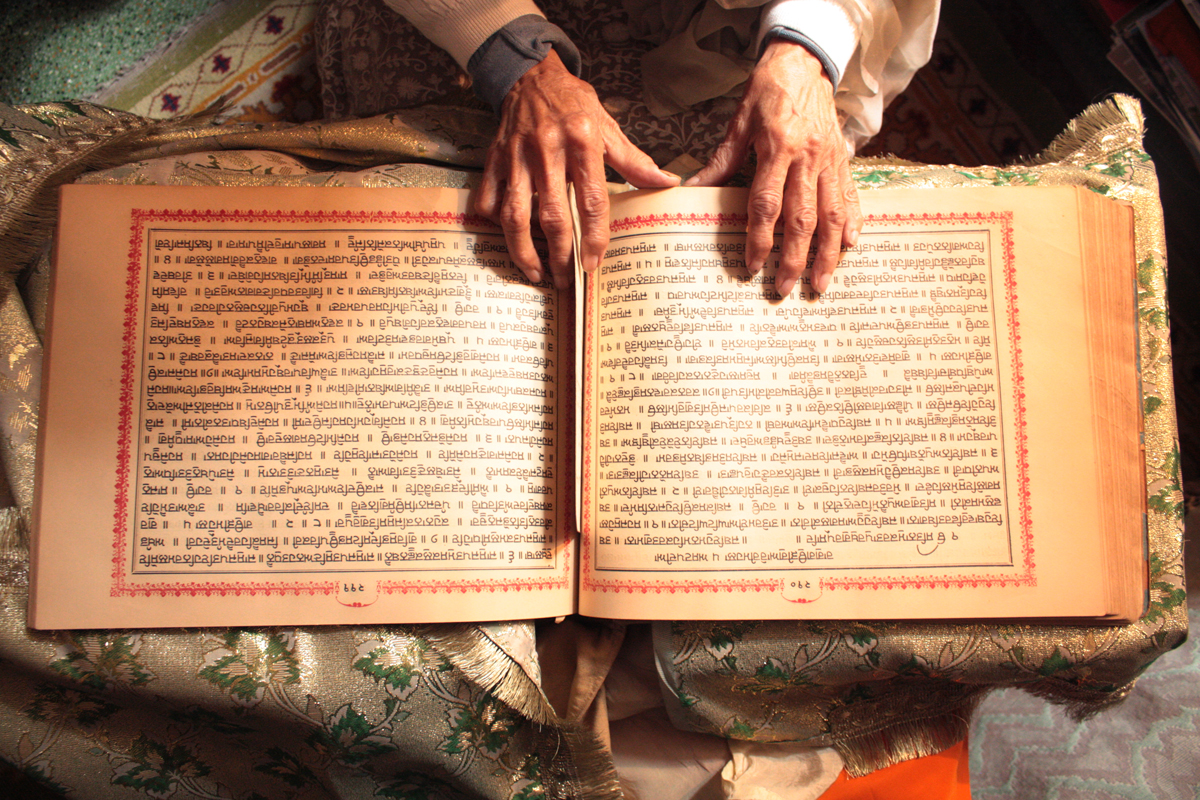

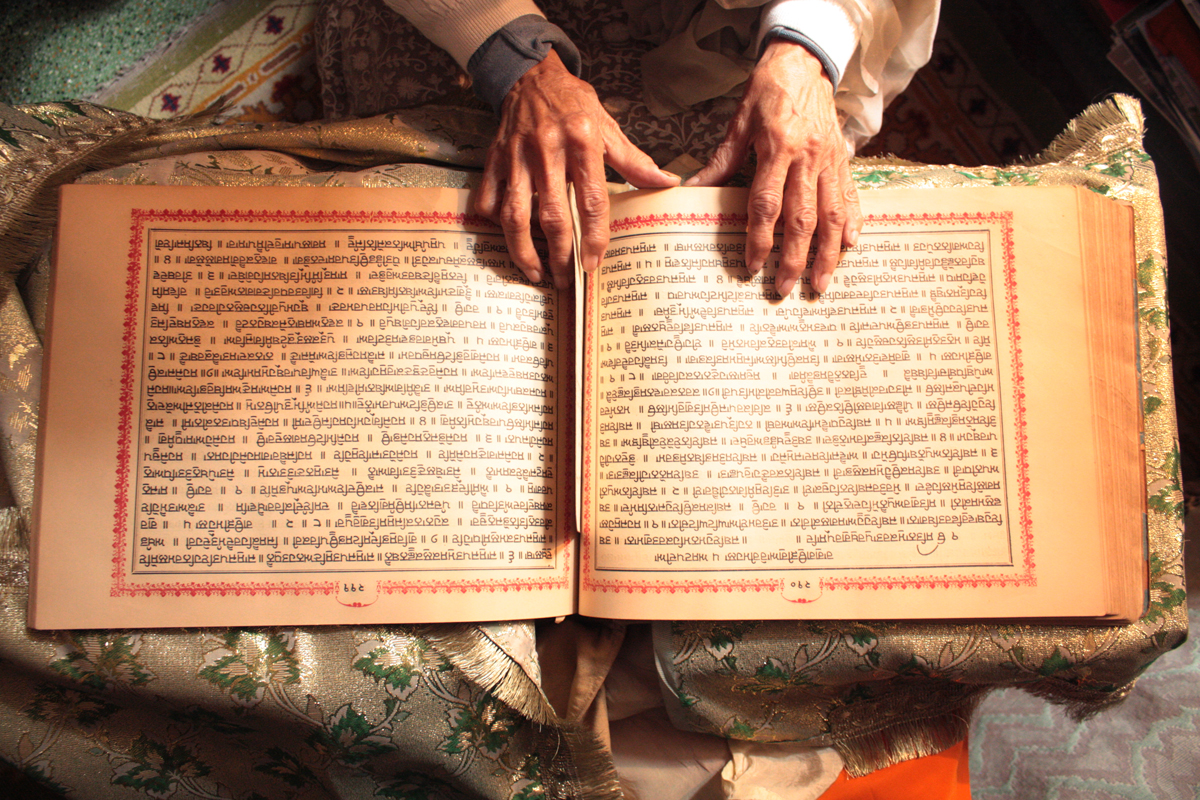

THE MUSICAL SOLACE OF MY MOTHER'S PRAYERS : THE GURU GRANTH SAHIB OF SUMITRA KAPUR

This Guru Granth Sahib, or baba ji, along with a few other possessons, was carried for the family by a neighbour from Rawalpindi to Mashobra months after the Partition.

A kirpaan that was kept along with the holy book and brought across. The third item carried was an antique American table clock from 1874, which rang every half hour.

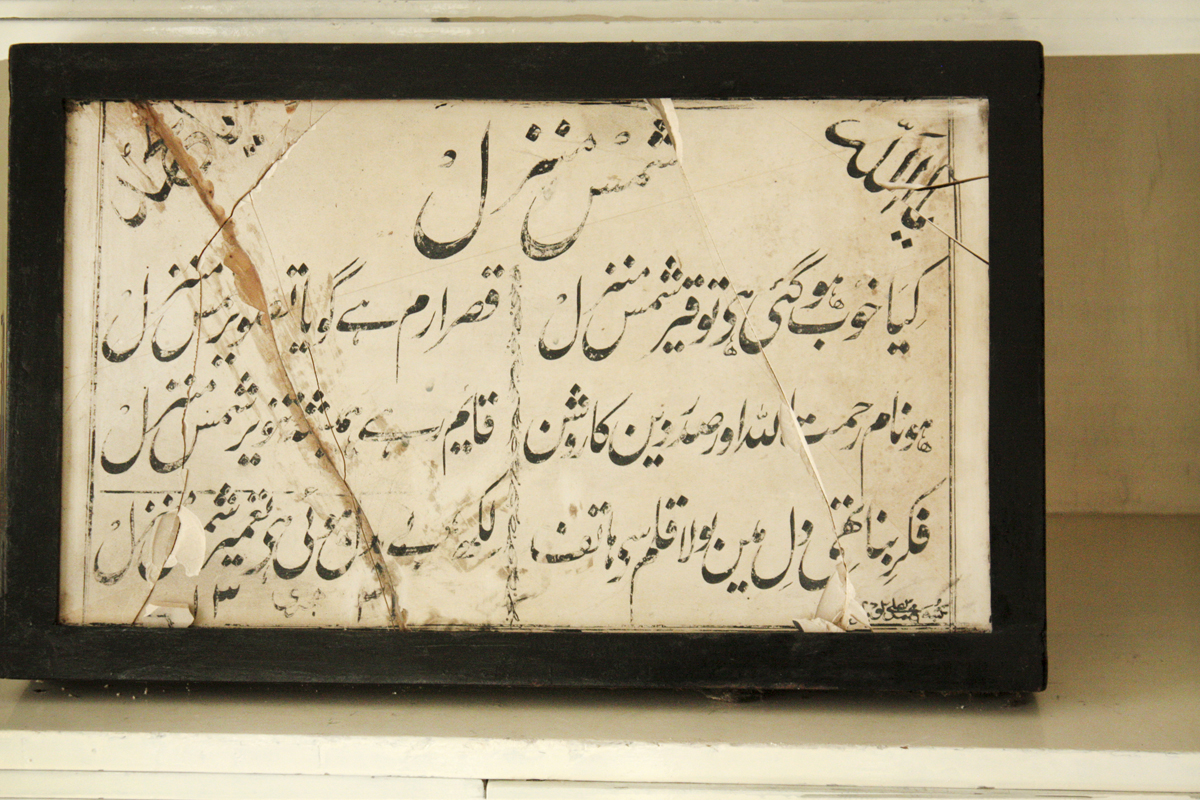

Sumitra Kapur, fluent in Urdu, Hindi, Farsi and Arabic is also my translator. Here she is translating parts of Mian Faiz Rabbani's stone plaque, carried from Jalandhar to Lahore.

Reading Rabbani's sahib's Urdu story titled, Ma aur Mamta. Kapur has also translated Prabhjot Kaur & Narenderpal Singh's 1947 six-act Punjabi drama, Kaafile. Read more

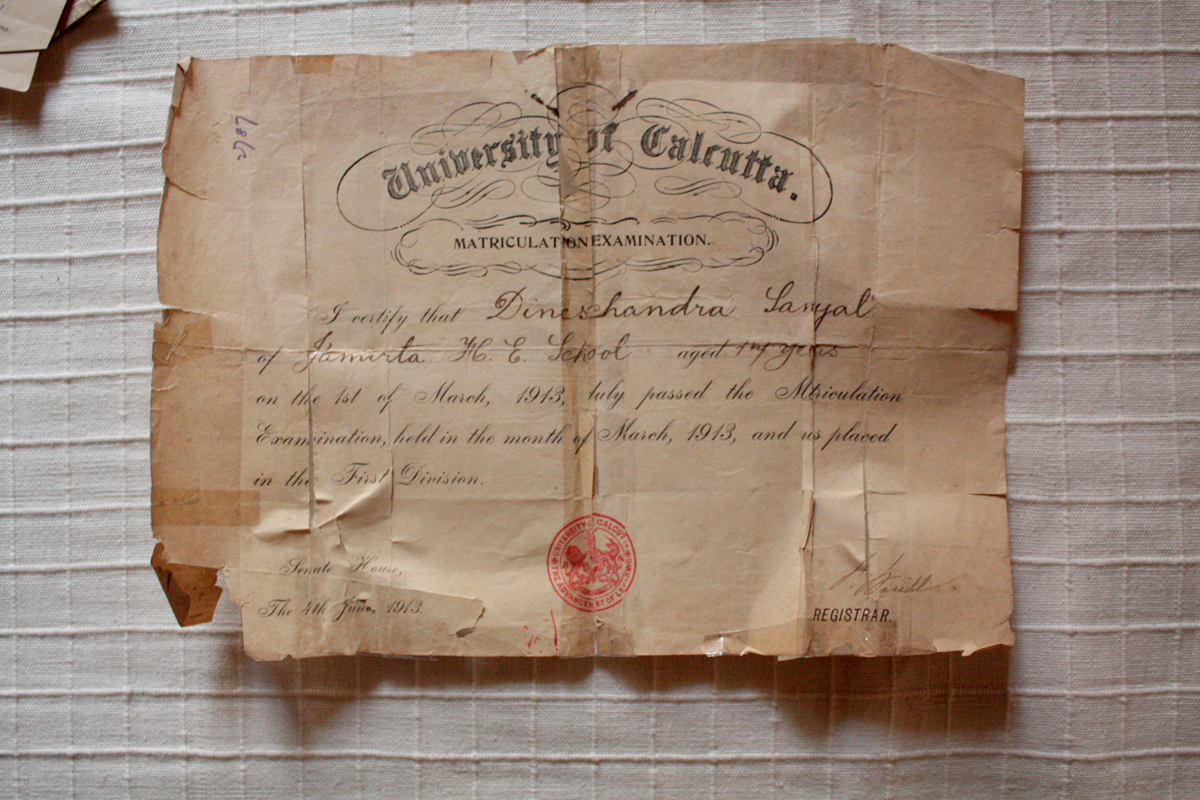

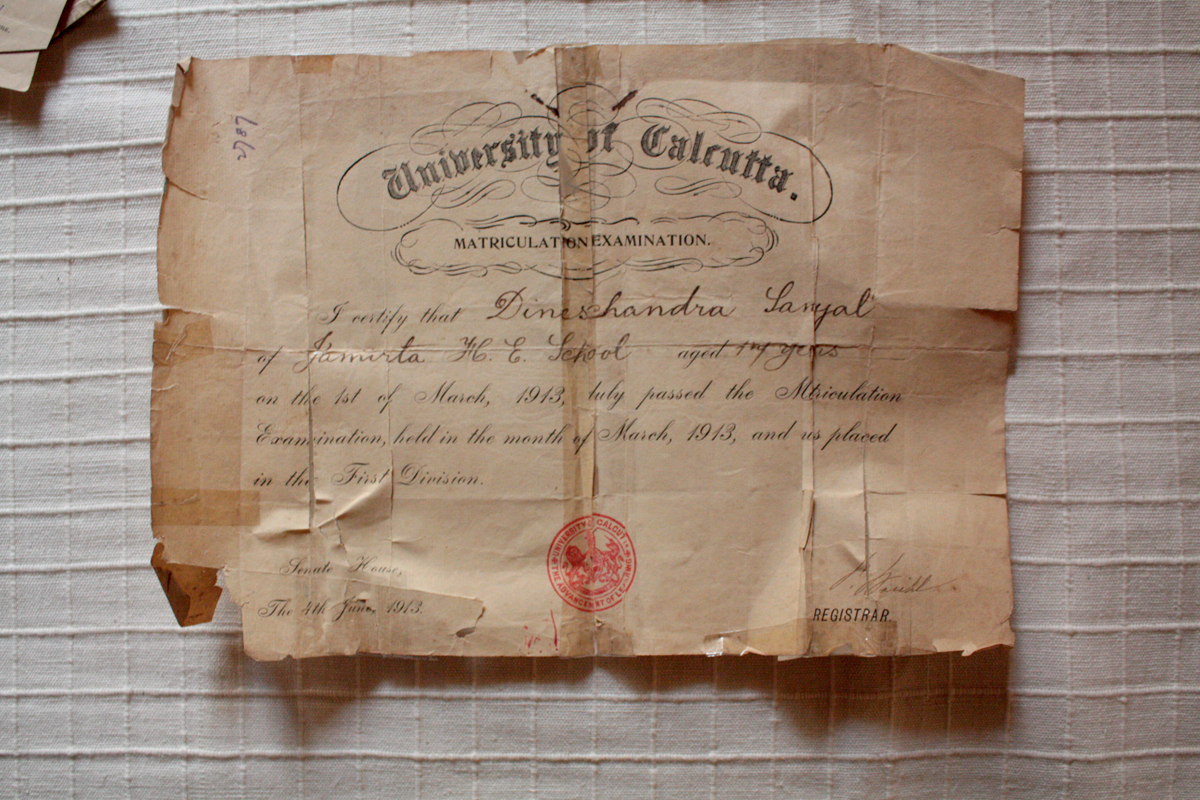

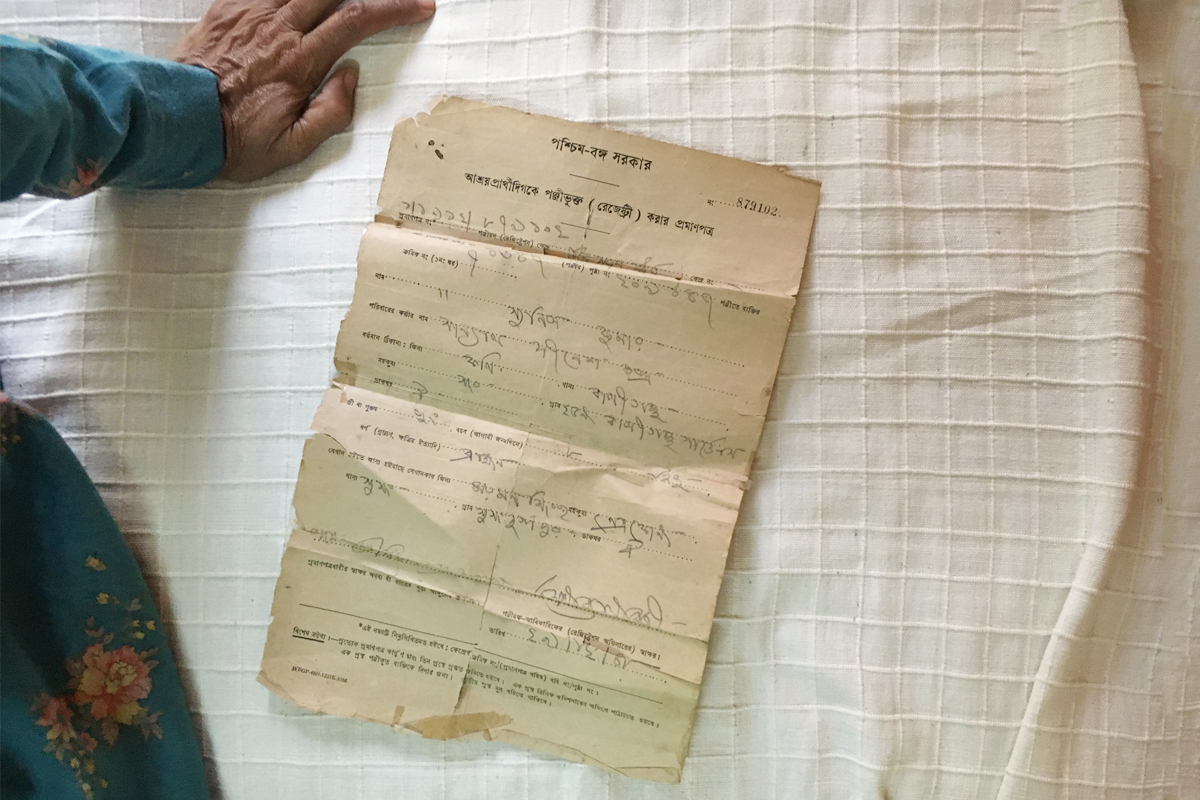

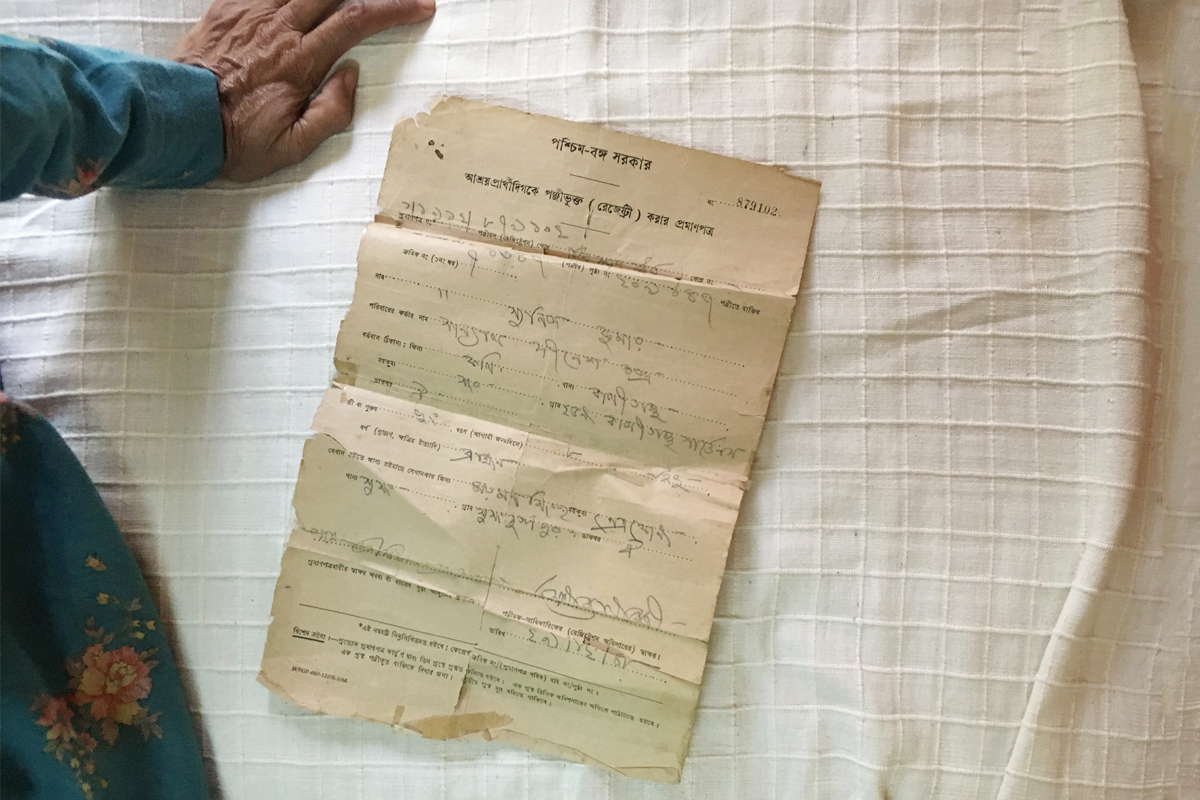

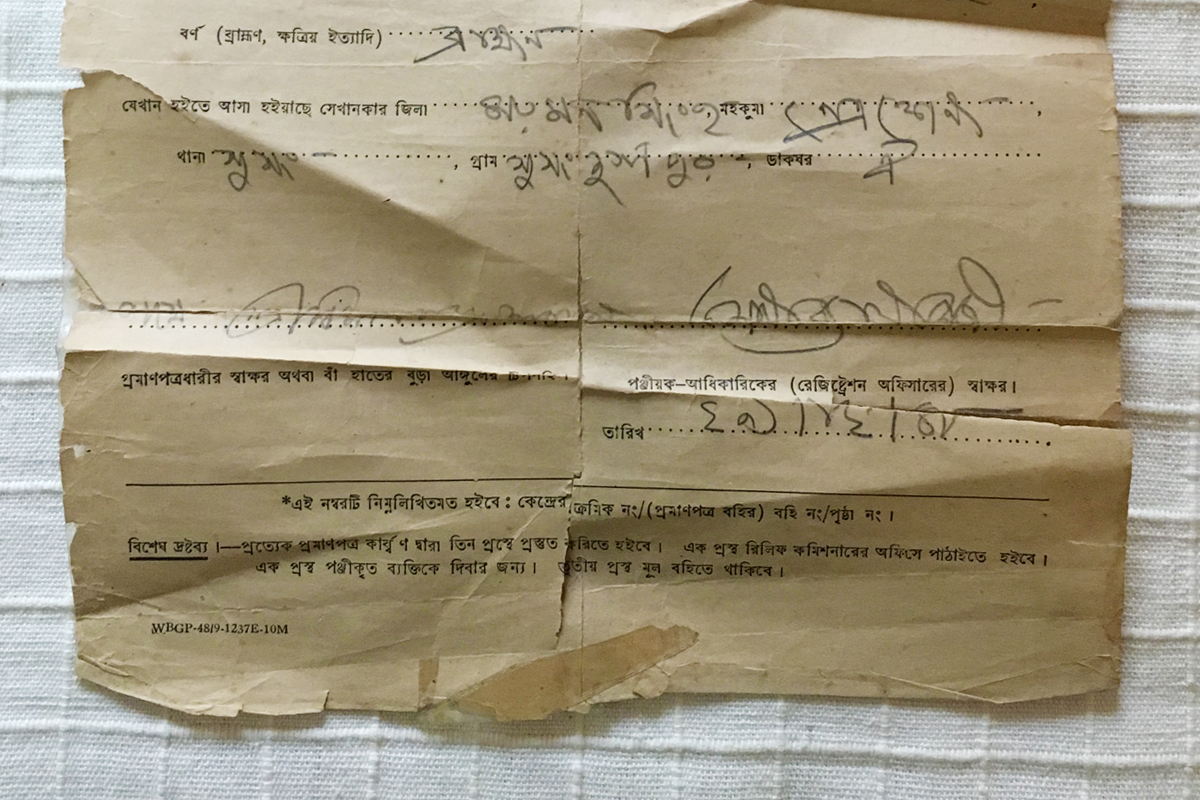

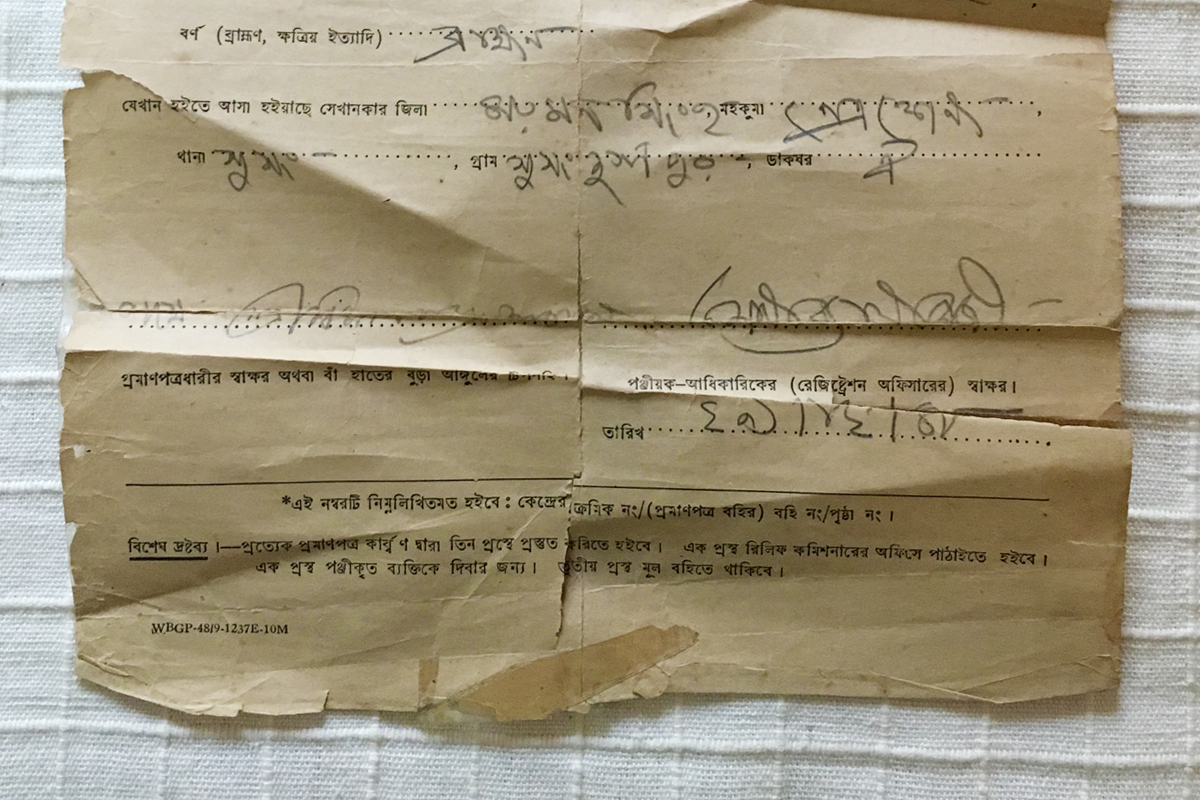

A CONVERSATION OF ERODED MEMORY : THE IDENTIFICATION CERTIFICATES OF SUNIL CHANDRA SANYAL

Bharati Sanyal translating the Refugee Certificate issued to her husband in 1948, from Bangla to English. “Registry Number: 1647. Name: Sunil Kumar, Family Head’s Name: Sanyal, Dineschandra.” Read more

Date of Registeration on the certificate is 29th December, 1948. Bharati Sanyal found this certificate and other papers in an old suitcase in the 1980s.

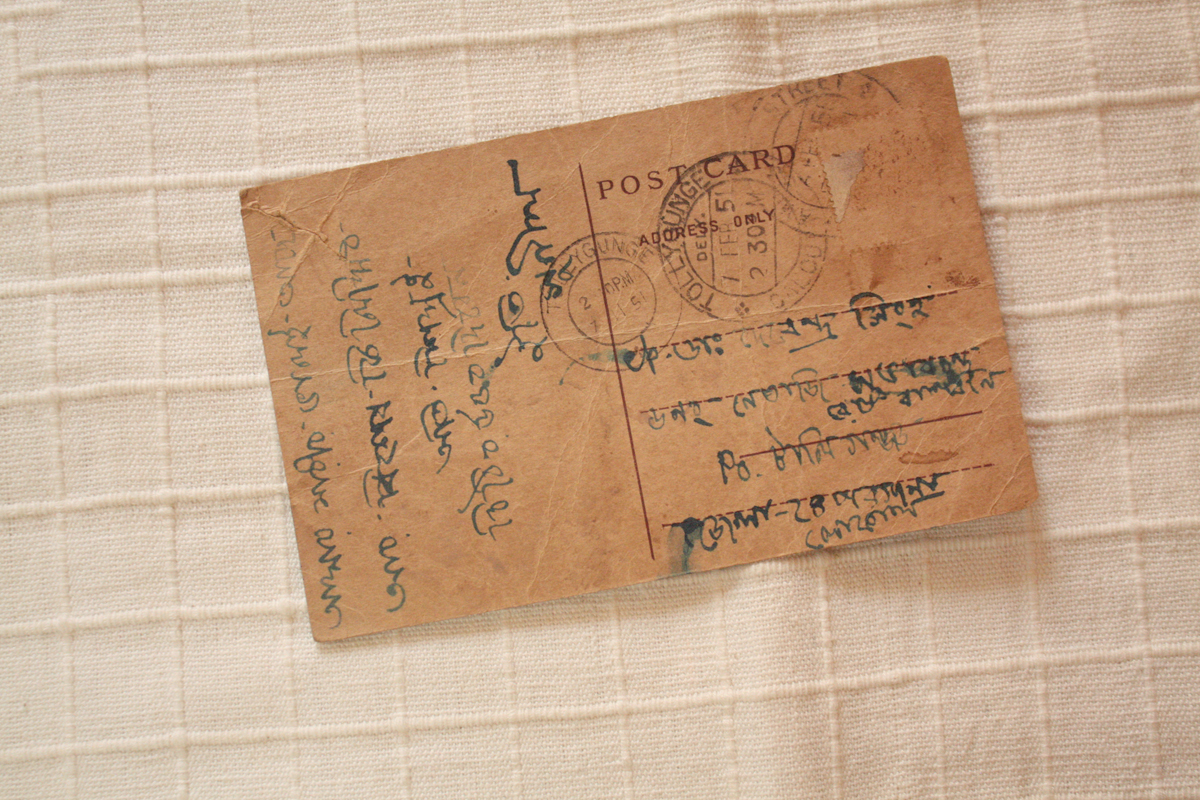

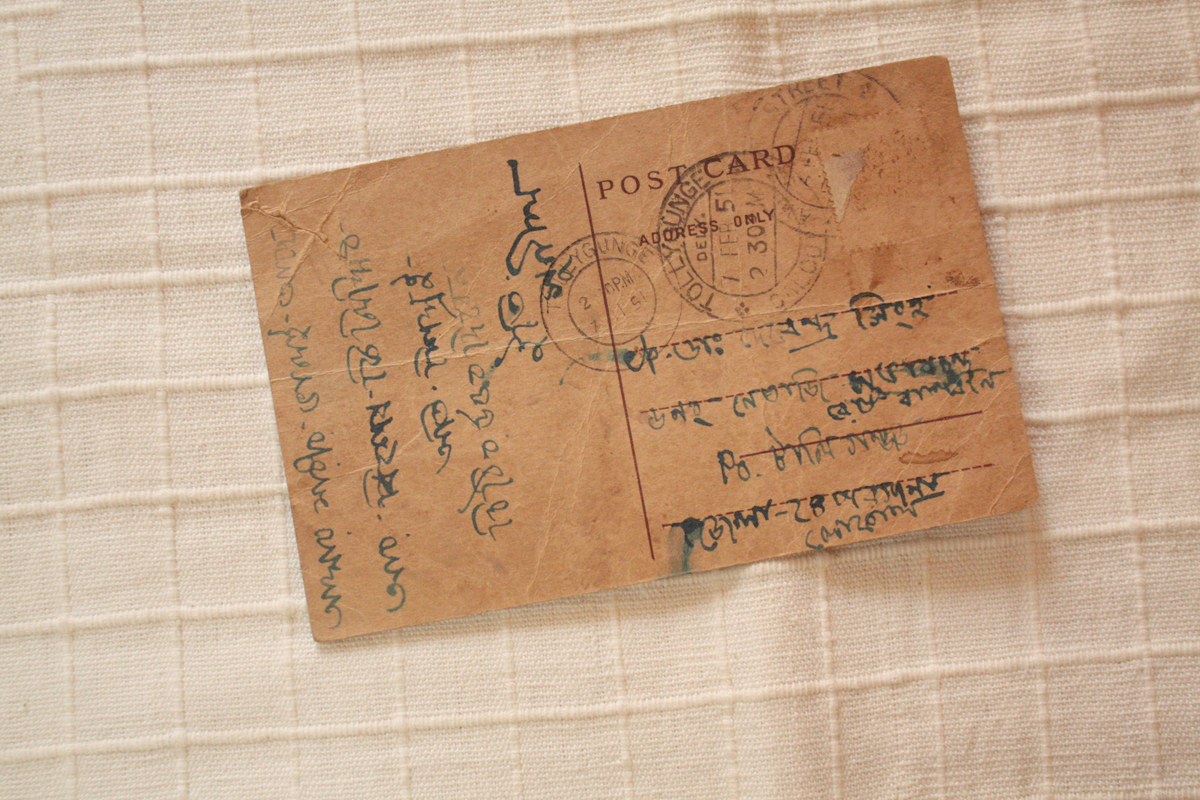

A postcard written by Sunil Sanyal to his father in 1951, while the family was living with separate relatives across the city. In it, ten year old Sunil requests his father to send across his school certificates. Read more

BETWEEN THIS SIDE AND THAT : THE SWORD OF AJIT KAUR KAPOOR

Ajit Kaur Kapoor (née Soni) was born in 1930 in Mirpur, a city in the then Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir, and migrated to India in November 1947. Read more

In 1947, she was nine months pregnant, living with her family in Mirpur, while her husband, Janak Singh, was working at the airfield in Rawalpindi. By the end of the year, he joined her.

This sword, along with 3 rupees and 9 annas was what Janak Singh has carried with him. It was issued to him at the Air Field in Rawalpindi. As they fled Mirpur, they were separated from their family, many of whom were killed or abducted.

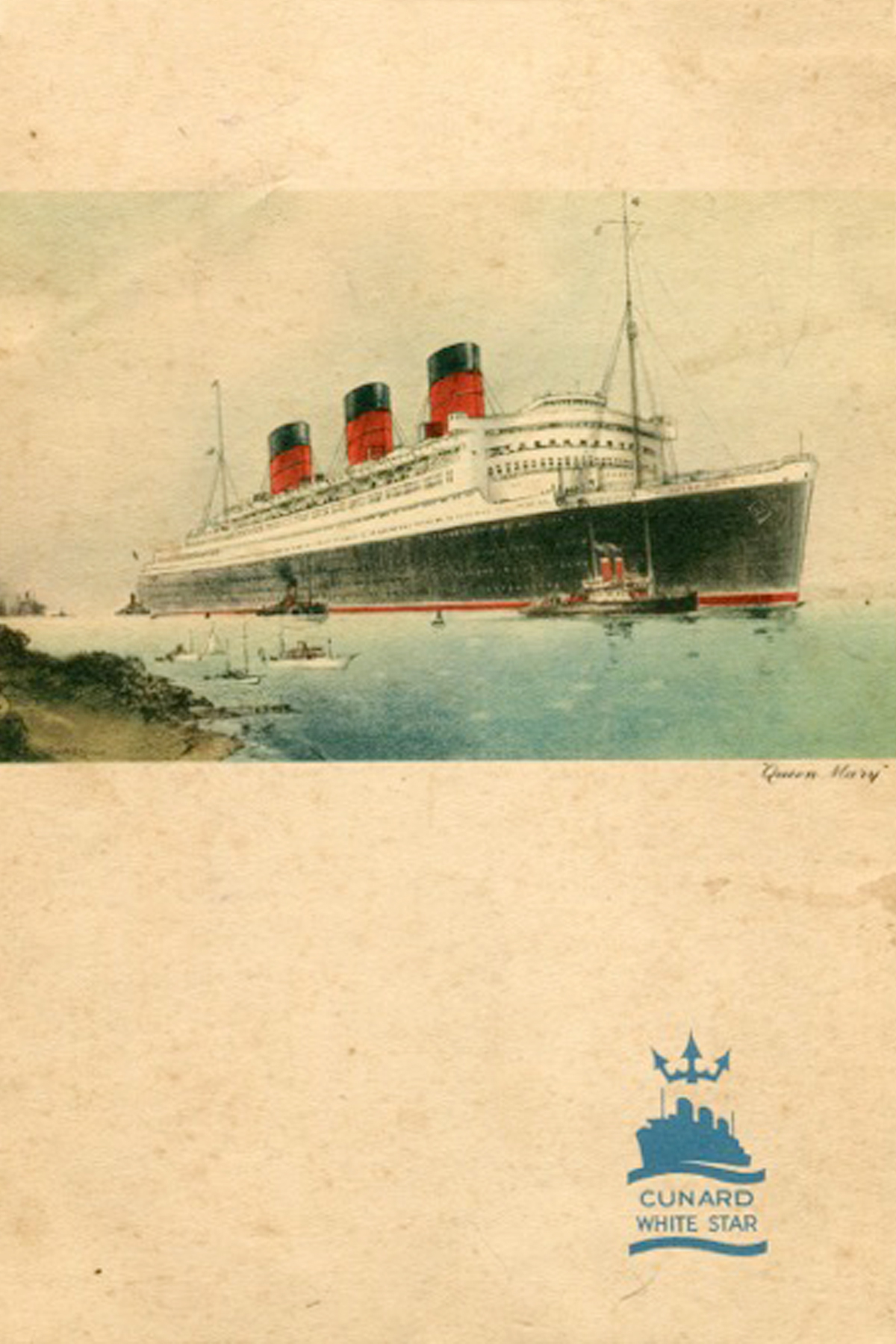

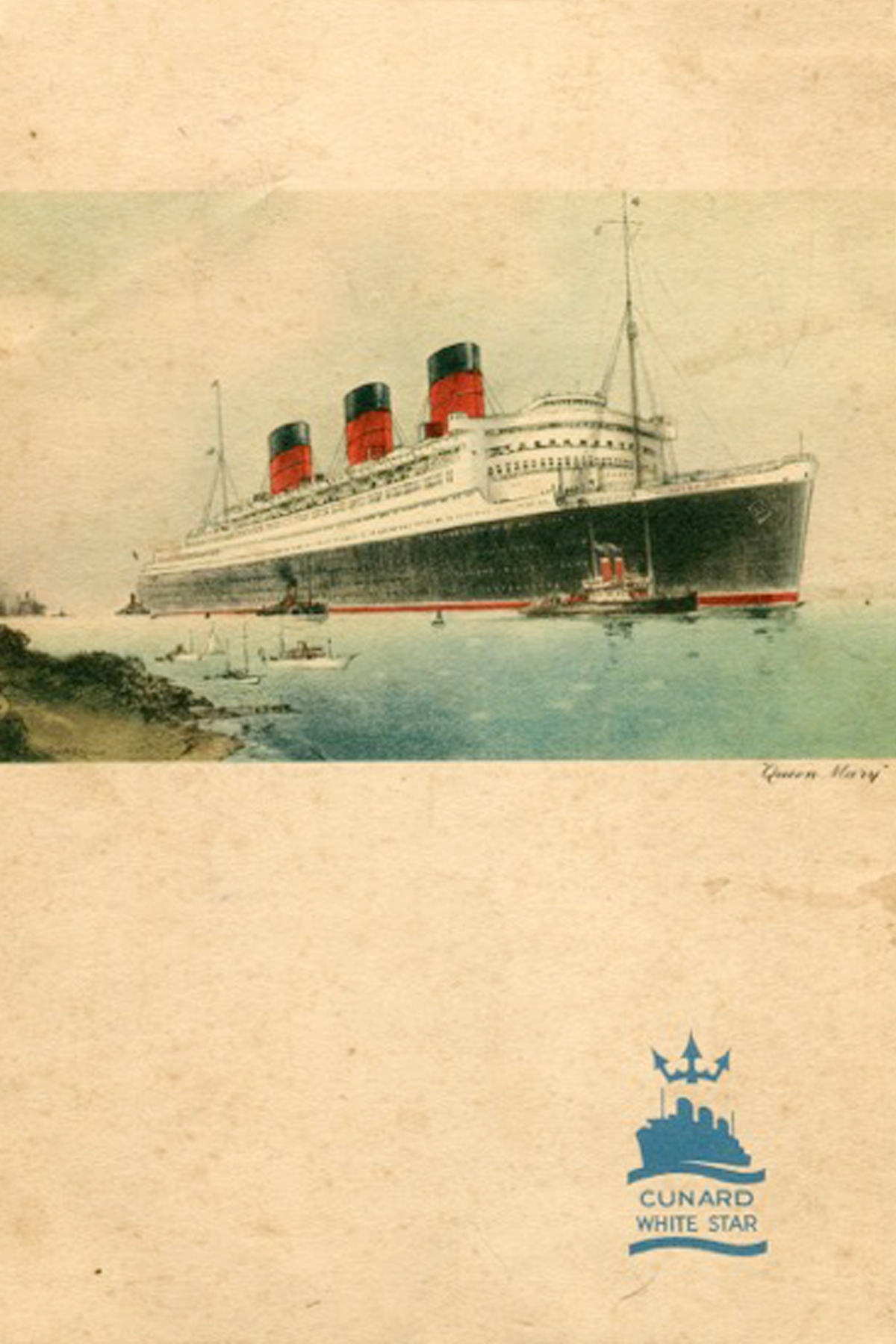

PASSAGE TO FREEDOM : THE WORLDLY TRUNK OF UMA SONDHI AHMAD

Uma Sondhi Ahmad, b.1931 in Jullundur, spent her life in Burma, England, Calcutta, Lahore, Jullundur and Mussourie, before finally migrating to Calcutta after Partition. Read more

Uma with the box she painted at Sacred Heart Convent School, as a teenager in Lahore. This box has since been bequeathed to her granddaughter, Diya.

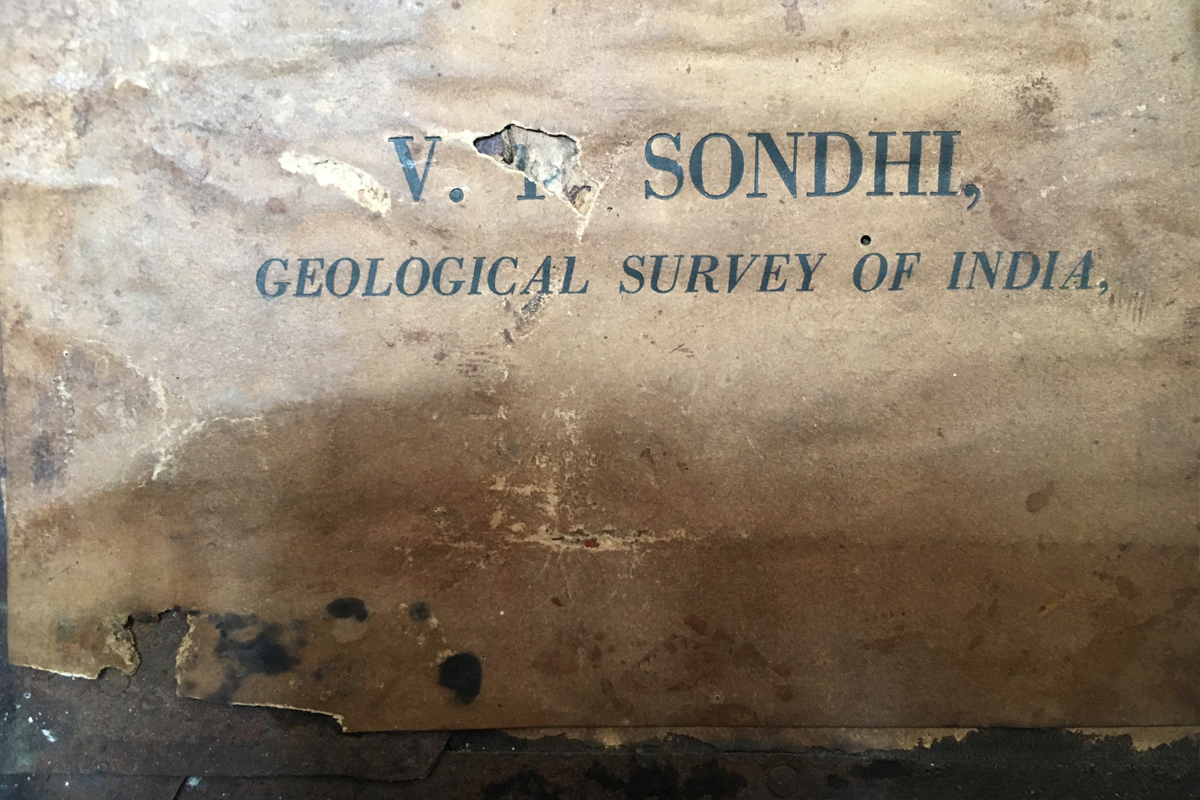

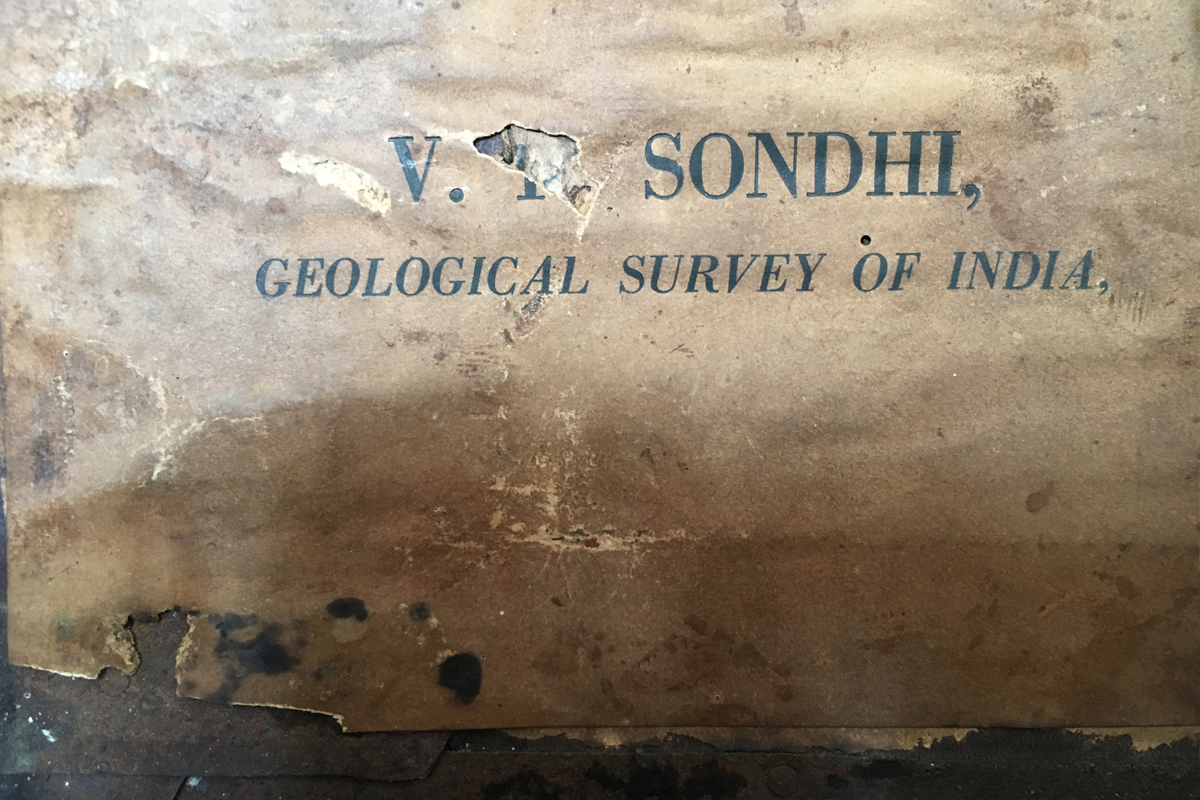

Ved Pal Sondhi (b.1903) obtained a M.Sc degree from Punjab University in 1925. He joined the Geological Survey of India in 1926 and was its Director General from 1955-58

One of the first posts V.P Sondhi took with the GSI was in the Southern Shan States of then British Burma, where he discovered caves full of coffins. Read more

The trunk that V.P Sondhi traveled with, during his years at the Geological Survey. It is made of soft leather, with an ornate metal latch to secure it shut. The trunk was presented to Uma in Lahore in 1945.

The paper of the label is weathered, but the name "V.P Sondhi, Geological Survey of India" is very much legible. Despite its age, the trunk is still covered with original luggage labels.

EXHIBITION

In 2015, Remnants was defended as a MFA thesis in the vitrines of Galerie FOFA, Concordia University, Montréal, a space that is 120 feet long and 10 feet wide. One side of the exhibit was a wall, upon which were mounted photographs and relevant texts from the various interviews, and the other side was glass. The inside of the vitrine ushered viewers through its restricted space almost in the same way that the large convoys of migration had, along a threshhold or a border. At the same time, looking into the glass vitrine from the outside created a sense of constant surveillance – of being policed – a watchfulness that had also accompanied the journeys of migration in 1947.

EPILOGUE

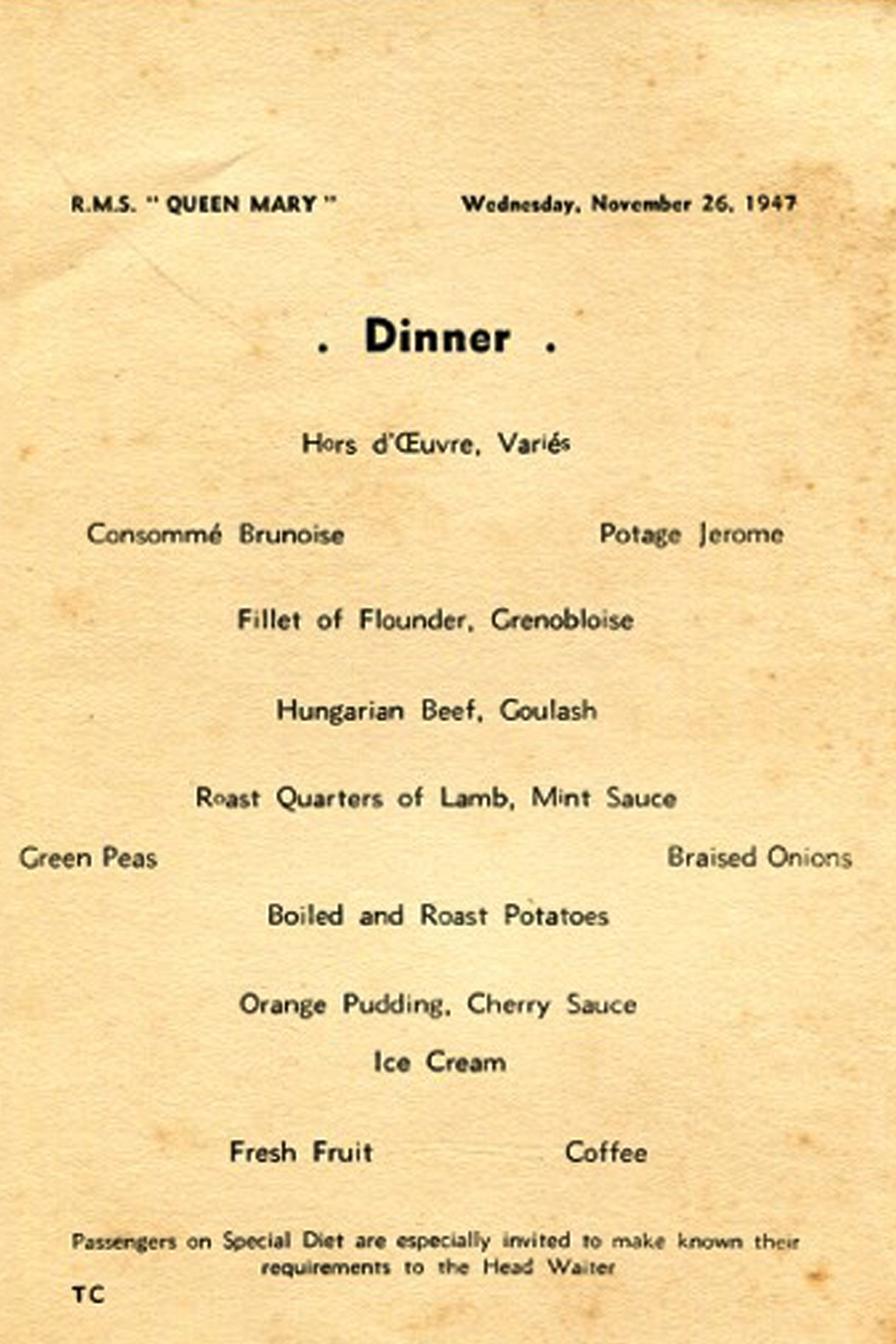

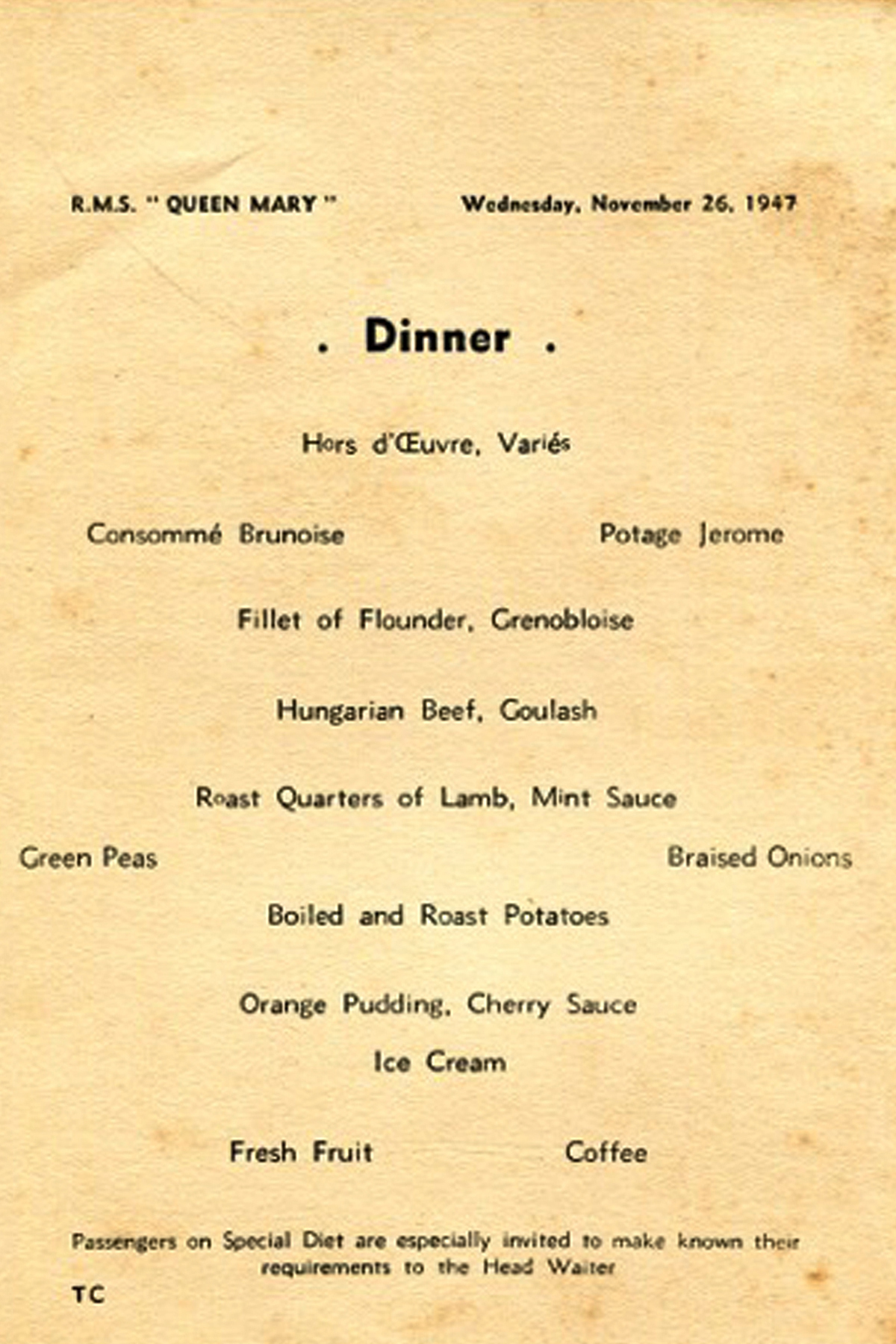

It has been years since Remnants was first exhibited as a visual art project, and then published as a book in 2017 to mark the seventieth anniversary of Independence and Partition. For many people, the fruition of a project – especially one that involved years of research – marks, in some ways, the culmination of that particular project. But that hasn't happened to me yet, nor do I think it ever will, for the field research for this work is still continuing. This is not with the active intention of writing another volume on the subject, but simply because the work cannot stop. Remnants has only opened the doors to a larger, more cavernous excavation of migratory memory. The reception of this work has helped me recognize how curious the youth of the subcontinent are about each other; how people still long to see "the other side" that they or their ancestors were born on. There may never come a day when the Radcliffe Line no longer separates India and Pakistan, but through gentle, continuous and meaningful conversations, one day this border might not feel so definite. I have hope that the understanding of a shared history, and subsequently, a shared pain and therefore, a shared healing, is possible.